Dam

Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, aquaculture, and navigability.

"[14] Roman planners introduced the then-novel concept of large reservoir dams which could secure a permanent water supply for urban settlements over the dry season.

In the Netherlands, a low-lying country, dams were often built to block rivers to regulate the water level and to prevent the sea from entering the marshlands.

Henry Russel of the Royal Engineers oversaw the construction of the Mir Alam dam in 1804 to supply water to the city of Hyderabad (it is still in use today).

[29] In the 1820s and 30s, Lieutenant-Colonel John By supervised the construction of the Rideau Canal in Canada near modern-day Ottawa and built a series of curved masonry dams as part of the waterway system.

It was the first French arch dam of the industrial era, and it was built by François Zola in the municipality of Aix-en-Provence to improve the supply of water after the 1832 cholera outbreak devastated the area.

William John Macquorn Rankine at the University of Glasgow pioneered the theoretical understanding of dam structures in his 1857 paper On the Stability of Loose Earth.

In 1928, Congress authorized the project to build a dam that would control floods, provide irrigation water and produce hydroelectric power.

[66] Scholars have noted that more research is needed to better understand the environmental impact of small dams[59] (e.g., their potential to alter the flow, temperature, sediment[67][52] and plant and animal diversity of a river).

Conversely, a wing dam is a structure that only partly restricts a waterway, creating a faster channel that resists the accumulation of sediment.

They are most common in northeastern Africa and the arid areas of Brazil while also being used in the southwestern United States, Mexico, India, Germany, Italy, Greece, France and Japan.

[71][72] Because tailings dams often store toxic chemicals from the mining process, modern designs incorporate an impervious geomembrane liner to prevent seepage.

Timber dams were widely used in the early part of the industrial revolution and in frontier areas due to ease and speed of construction.

Timber dams were once numerous, especially in the North American West, but most have failed, been hidden under earth embankments, or been replaced with entirely new structures.

Made commonly of wood, concrete, or steel sheet piling, cofferdams are used to allow construction on the foundation of permanent dams, bridges, and similar structures.

An example would be the eruptions of the Uinkaret volcanic field about 1.8 million–10,000 years ago, which created lava dams on the Colorado River in northern Arizona in the United States.

A variant on this simple model uses pumped-storage hydroelectricity to produce electricity to match periods of high and low demand, by moving water between reservoirs at different elevations.

Significant other engineering and engineering geology considerations when building a dam include: Impact is assessed in several ways: the benefits to human society arising from the dam (agriculture, water, damage prevention and power), harm or benefit to nature and wildlife, impact on the geology of an area (whether the change to water flow and levels will increase or decrease stability), and the disruption to human lives (relocation, loss of archeological or cultural matters underwater).

Water releases from a reservoir including that exiting a turbine usually contain very little suspended sediment, and this, in turn, can lead to scouring of river beds and loss of riverbanks; for example, the daily cyclic flow variation caused by the Glen Canyon Dam was a contributor to sand bar erosion.

Studies have demonstrated the key role played by tributaries in the downstream direction from the main river impoundment, which influenced local environmental conditions and beta diversity patterns of each biological group.

[83] A large dam can cause the loss of entire ecospheres, including endangered and undiscovered species in the area, and the replacement of the original environment by a new inland lake.

However, this is a mistaken assumption, because the relatively marginal stress attributed to the water load is orders of magnitude lesser than the force of an earthquake.

[87] While dams and the water behind them cover only a small portion of earth's surface, they harbour biological activity that can produce large quantities of greenhouse gases.

Nick Cullather argues in Hungry World: America's Cold War Battle Against Poverty in Asia that dam construction requires the state to displace people in the name of the common good, and that it often leads to abuses of the masses by planners.

Hydroelectric generation can be vulnerable to major changes in the climate, including variations in rainfall, ground and surface water levels, and glacial melt, causing additional expenditure for the extra capacity to ensure sufficient power is available in low-water years.

In total, renewed sediment delivery caused approximately 60 ha of delta growth, and also resulted in increased river braiding.

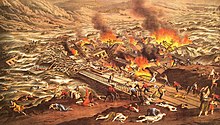

During an armed conflict, a dam is to be considered as an "installation containing dangerous forces" due to the massive impact of possible destruction on the civilian population and the environment.

As such, it is protected by the rules of international humanitarian law (IHL) and shall not be made the object of attack if that may cause severe losses among the civilian population.

To facilitate the identification, a protective sign consisting of three bright orange circles placed on the same axis is defined by the rules of IHL.

A notable case of deliberate dam failure (prior to the above ruling) was the Royal Air Force 'Dambusters' raid on Germany in World War II (codenamed "Operation Chastise"), in which three German dams were selected to be breached in order to damage German infrastructure and manufacturing and power capabilities deriving from the Ruhr and Eder rivers.