Taoist meditation

The opposite direction of adoption has also taken place, when the martial art of Taijiquan, "great ultimate fist", became one of the practices of modern Daoist monks, while historically it was not among traditional techniques.

[1] Ding 定 literally means "decide; settle; stabilize; definite; firm; solid" and early scholars such as Xuanzang used it to translate Sanskrit samadhi "deep meditative contemplation" in Chinese Buddhist texts.

Kohn says the word guan, "intimates the role of Daoist sacred sites as places of contact with celestial beings and observation of the stars".

It thus means that the meditator, by an act of conscious concentration and focused intention, causes certain energies to be present in certain parts of the body or makes specific deities or scriptures appear before his or her mental eye.

[10] Owing to the consensus that proto-Daoist Huang-Lao philosophers at the Jixia Academy in Qi composed the core Guanzi, Neiye meditation techniques are technically "Daoistic" rather than "Daoist".

[11] Neiye Verse 8 associates dingxin 定心 "stabilizing the mind" with acute hearing and clear vision, and generating jing 精 "vital essence".

With a stable mind at your core, With the eyes and ears acute and clear, And with the four limbs firm and fixed, You can thereby make a lodging place for the vital essence.

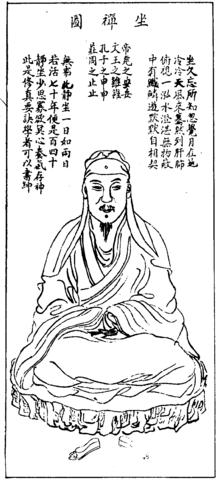

[16] It is to be undertaken when you are sitting in a calm and unmoving position, and it enables you to set aside the disturbances of perceptions, thoughts, emotions, and desires that normally fill your conscious mind."

[23] Dichu xuanjian 滌除玄覽 "cleanse the mirror of mysteries" and jingchu qi she 敬除其舍 "diligently clean out its lodging place" (13)[24] have the same verb chu "eliminate; remove".

Wang Bi (226–249) was a scholar of Xuanxue "mysterious studies; neo-Daoism", which adapted Confucianism to explain Daoism, and his version eventually became the standard Tao Te Ching interpretation.

Richard Wilhelm said Wang Bi's commentary changed the Tao Te Ching "from a compendiary of magical meditation to a collection of free philosophical aperçus".

Two well-known examples of mental disciplines are Confucius and his favorite disciple Yan Hui discussing xinzhai 心齋 "heart-mind fasting" and zuowang "sitting forgetting".

"I slough off my limbs and trunk," said Yen Hui, "dim my intelligence, depart from my form, leave knowledge behind, and become identical with the Transformational Thoroughfare.

(9)[28] Roth interprets this "slough off my limbs and trunk" (墮肢體) phrase to mean, "lose visceral awareness of the emotions and desires, which for the early Daoists, have 'physiological' bases in the various organs".

But it is favored by scholars who channel the vital breath and flex the muscles and joints, men who nourish the physical form so as to emulate the hoary age of Progenitor P'eng [i.e., Peng Zu].

Some writing on a Warring States era jade artifact could be an earlier record of breath meditation than the Neiye, Tao Te Ching, or Zhuangzi.

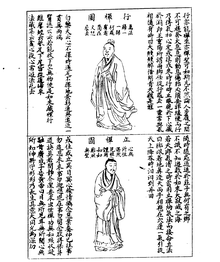

[36] This rhymed inscription entitled xingqi 行氣 "circulating qi" was inscribed on a dodecagonal block of jade, tentatively identified as a pendant or a knob for a staff.

[40] The text uses xinshu 心術 "mind techniques" both as a general term for "inner cultivation" meditation practices and as a specific name for the Guanzi chapters.

The adept envisions the yellow and red essences of the sun and moon, which activates Laozi and Yunü 玉女 "Jade Woman" within the abdomen, producing the shengtai 聖胎 "sacred embryo".

Whether in the shrine of a ghost, in the mountains or forests, in a place suffering the plague, within a tomb, in bush inhabited by tigers and wolves, or in the habitation of snakes, all evils will go far away as long as one remains diligent in the preservation of Unity.

(18)[52]The Baopuzi also compares shouyi meditation with a complex mingjing 明鏡 "bright mirror" multilocation visualization process through which an individual can mystically appear in several places at once.

The world of meditation in this tradition is incomparably rich and colorful, with gods, immortals, body energies, and cosmic sprouts vying for the adept's attention.

[54]Beginning around 400 CE, the Lingbao "Numinous Treasure" School eclectically adopted concepts and practices from Daoism and Buddhism, which had recently been introduced to China.

[55] The Lingbao School added the Buddhist concept of reincarnation to the Daoist tradition of xian "immortality; longevity", and viewed meditation as a means to unify body and spirit.

The (c. late 5th-century) The Northern Celestial Masters text Xishengjing "Scripture of Western Ascension" recommends cultivating an empty state of consciousness called wuxin 無心 (lit.

The 8th century was a "heyday" of Daoist meditation;[54] recorded in works such as Sun Simiao's Cunshen lianqi ming 存神煉氣銘 "Inscription on Visualization of Spirit and Refinement of Energy", Sima Chengzhen 司馬承禎's Zuowanglun "Essay on Sitting in Forgetfulness", and Wu Yun 吳筠's Shenxian kexue lun 神仙可學論 "Essay on How One May Become a Divine Immortal through Training".

These Daoist classics reflect a variety of meditation practices, including concentration exercises, visualizations of body energies and celestial deities to a state of total absorption in the Dao, and contemplations of the world.

The (9th century) Qingjing Jing "Scripture of Clarity and Quiescence" associates the Tianshi tradition of a divinized Laozi with Daoist guan and Buddhist vipaśyanā methods of insight meditation.

Western knowledge of Daoist meditation was stimulated by Richard Wilhelm's (German 1929, English 1962) The Secret of the Golden Flower translation of the (17th century) neidan text Taiyi jinhua zongzhi 太乙金華宗旨.

In the 20th century, the Qigong movement has incorporated and popularized Daoist meditation, and "mainly employs concentrative exercises but also favors the circulation of energy in an inner-alchemical mode".