Mantra

These phrases may have spiritual interpretations such as a name of a deity, a longing for truth, reality, light, immortality, peace, love, knowledge, and action.

[10] Both Sanskrit mántra and the equivalent Avestan mąθra go back to the common Proto-Indo-Iranian *mantram, consisting of the Indo-European *men "to think" and the instrumental suffix *trom.

[18][19] According to Bernfried Schlerath, the concept of sātyas mantras is found in Indo-Iranian Yasna 31.6 and the Rigveda, where it is considered structured thought in conformity with the reality or poetic (religious) formulas associated with inherent fulfillment.

[25] Farquhar concludes that mantras are a religious thought, prayer, sacred utterance, but also believed to be a spell or weapon of supernatural power.

[27] Agehananda Bharati defines mantra, in the context of the Tantric school of Hinduism, to be a combination of mixed genuine and quasi-morphemes arranged in conventional patterns, based on codified esoteric traditions, passed on from a guru to a disciple through prescribed initiation.

[30] By comparing the Old Indic Vedic and Old Iranian Avestan traditions, Gonda concludes that in the oldest texts, mantras were "means of creating, conveying, concentrating and realizing intentional and efficient thought, and of coming into touch or identifying oneself with the essence of the divinity".

He suggests that verse mantras are metered and harmonized to mathematical precision (for example, in the viharanam technique), which resonate, but a lot of them are a hodgepodge of meaningless constructs such as are found in folk music around the world.

These saman chant mantras are also mostly meaningless, cannot be literally translated as Sanskrit or any Indian language, but nevertheless are beautiful in their resonant themes, variations, inversions, and distribution.

It has an emotive numinous effect, it mesmerizes, it defies expression, and it creates sensations that are by definition private and at the heart of all religions and spiritual phenomena.

In other words,[46] in Vedic times, mantras were recited a practical, quotidian goal as intention, such as requesting a deity's help in the discovery of lost cattle, cure of illness, succeeding in competitive sport or journey away from home.

In a later period of Hinduism,[47] mantras were recited with a transcendental redemptive goal as intention, such as escape from the cycle of life and rebirth, forgiveness for bad karma, and experiencing a spiritual connection with the god.

[48] These six limbs are: Seer (Rishi), Deity (Devata), Seed (Beeja), Energy (Shakti), Poetic Meter (chanda), and Lock (Kilaka).

[50] According to this school, any shloka from holy Hindu texts like the Vedas, Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Sutra, even the Mahabharata, Ramayana, Durga saptashati or Chandi is a mantra, thus can be part of the japa, repeated to achieve a numinous effect.

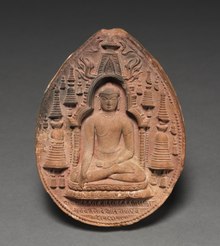

The Sanskrit version of this mantra is:ye dharmā hetuprabhavā hetuṃ teṣāṃ tathāgato hyavadat, teṣāṃ ca yo nirodha evaṃvādī mahāśramaṇaḥThe phrase can be translated as follows:Of those phenomena which arise from causes: Those causes have been taught by the Tathāgata (Buddha), and their cessation too - thus proclaims the Great Ascetic.Early Buddhist texts also contain various apotropaic chants which have similar functions to Vedic mantras.

According to the American Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield:[77]The use of mantra or the repetition of certain phrases in Pali is a highly common form of meditation in the Theravada tradition.

[79] Another popular mantra in Thai Buddhism is Samma-Araham, referring to the Buddha who has 'perfectly' (samma) attained 'perfection in the Buddhist sense' (araham), used in Dhammakaya meditation.

Another early and influential Mahayana "mantra" or dharani is the Arapacana alphabet (of non-Sanskrit origin, possibly Karosthi) which is used as a contemplative tool in the Long Prajñāpāramitā sutras.

[85][86] The entire alphabet runs:[85] a ra pa ca na la da ba ḍa ṣa va ta ya ṣṭa ka sa ma ga stha ja śva dha śa kha kṣa sta jña rta ha bha cha sma hva tsa bha ṭha ṇa pha ska ysa śca ṭa ḍhaIn this practice, each letter stood for a specific idea (for example, "a" stands for non-arising (anutpada), and pa stands for "ultimate truth" (paramārtha).

"[101] One of Kūkai's distinctive contributions was to take this symbolic association even further by saying that there is no essential difference between the syllables of mantras and sacred texts, and those of ordinary language.

In the Mahavairocana Sutra which is central to Shingon Buddhism it says: "Thanks to the original vows of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, a miraculous force resides in the mantras, so that by pronouncing them one acquires merit without limits".

Nichiren Buddhist practice focuses on the chanting of one single mantra or phrase: Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō (南無妙法蓮華経, which means "Homage to the Lotus Sutra").

The book Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism by Lama Anagarika Govinda, gives a classic example of how such a mantra can contain many levels of symbolic meaning.

According to Tibetan Buddhism, this mantra (Om tare tutare ture soha) can not only eliminate disease, troubles, disasters, and karma, but will also bring believers blessings, longer life, and even the wisdom to transcend one's circle of reincarnation.

Only a person who has been initiated into the vibrational realms, who has actually experienced this level of reality, can fully understand the Science of Letters...the Nomokar Mantra is a treasured gift to humanity of unestimable (sic) worth for the purification, upliftment and spiritual evolution of everyone.".

As you recite "Namo Arihantanam," visualize a bright white light at the base of your spine and feel the energy rising up through your body while bowing to all Arihants at the Same Time.

As you recite "Eso Panch Namukaro," focus on your sixth chakra (Ajna), located in the center of your forehead Visualize a deep purple light here representing intuition and spiritual insight.

[119] In the pratikramana prayer, Jains repeatedly seek forgiveness from various creatures—even from ekindriyas or single sensed beings like plants and microorganisms that they may have harmed while eating and doing routine activities.

"[121] In their daily prayers and samayika, Jains recite the following Iryavahi sutra in Prakrit, seeking forgiveness from literally all creatures while involved in routine activities:[122] May you, O Revered One, voluntarily permit me.

After the arrival of Buddhism many Taoist sects started to use Sanskrit syllables in their mantras or talisman as a way to enhance one's spiritual power aside from the traditional Han incantations.

Taoist believe this incantation to be the heart mantra of Pu Hua Tian Zun which will protect them from bad qi and calm down emotions.