Daqin

Its medieval incarnation was described in histories during the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) onwards as Fulin (Chinese: 拂菻; pinyin: Fúlǐn), which Friedrich Hirth and other scholars have identified as the Byzantine Empire.

Chinese sources describe several ancient Roman embassies arriving in China, beginning in 166 AD and lasting into the 3rd century.

These early embassies were said to arrive by a maritime route via the South China Sea in the Chinese province of Jiaozhi (now northern Vietnam).

Later recorded embassies arriving from the Byzantine Empire, lasting from the 7th to 11th centuries, ostensibly took an overland route following the Silk Road, alongside other Europeans in Medieval China.

[7] While some scholars of the 20th century believed that Fulin was a transliteration of Ephraim, a reference to the Biblical Northern Kingdom, Samuel N. C. Lieu highlights how more recent scholarship has deduced that Fulin is most likely derived from the Persianate word for the Roman Empire shared by several contemporaneous Iranian languages (Middle Persian: hrwm; Parthian: transl.

China never managed to reach the Roman Empire directly in antiquity, although general Ban Chao sent Gan Ying as an envoy to "Daqin" in 97 AD.

[9][10]Gan Ying gives a very idealistic view of Roman governance which is likely the result of some story he was told while visiting the Persian Gulf in 97 AD.

This country produces plenty of gold [and] silver, [and of] rare and precious they have luminous jade, "bright moon pearls", Haiji rhinoceroses, coral, yellow amber, opaque glass, whitish chalcedony [i.e., langgan], red cinnabar, green gemstones, gold-thread embroideries, woven gold-threaded net, delicate polychrome silks painted with gold, and asbestos cloth.

The king of this country always wanted to send envoys to the Han, but Anxi, wishing to control the trade in multi-coloured Chinese silks, blocked the route to prevent [the Romans] getting through [to China].

The 19th-century sinologist Friedrich Hirth translated the passages and identified the places named in them, which have been edited by Jerome S. Arkenberg in 2000 (with Wade-Giles spelling):[3] Formerly T'iao-chih was wrongly believed to be in the west of Ta-ts'in; now its real position is known to be east.

[3]The Weilüe also noted that the Daqin had small "dependent" vassal states, too many to list as the text claims, yet it mentions some as being the Alexandria-Euphrates or Charax Spasinu ("Ala-san"), Nikephorium ("Lu-fen"), Palmyra ("Ch'ieh-lan"), Damascus ("Hsien-tu"), Emesa ("Si-fu"), and Hira ("Ho-lat").

[3] Perhaps some of these are in reference to certain states that were temporarily conquered during the Roman–Parthian Wars (66 BC – 217 AD) when, for instance, the army of Roman Emperor Trajan reached the Persian Gulf and captured Characene, the capital of which was Charax Spasinu.

However, John E. Hill provides evidence that it was most likely Petra (in the Nabataean Kingdom), given the directions and distance from "Yuluo" (i.e. Al Karak) and the fact that it fell under Roman dominion in 106 AD when it was annexed by Trajan.

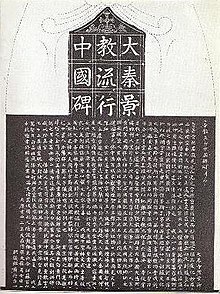

The Nestorian Stele erected in 781 in the Tang capital Chang'an contains an inscription that briefly summarizes the knowledge about Daqin in the Chinese histories written up to that point and notes how only the "luminous" religion (i.e. Christianity) was practiced there.

It has also been suggested that the capital of Daqin described in those works is a conflation of multiple cities, chiefly Rome, Antioch and Alexandria.

[16] However, the Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang, which identified Daqin and "Fulin" (拂菻; i.e. Primus, the Byzantine Empire) as the same countries, noted a different capital city (Constantinople), one that had walls of "enormous height" and was eventually besieged by the commander "Móyì" (Chinese: 摩拽伐之; Pinyin: Móyì fá zhī) of the Da shi (大食; i.e. the Arabs).

[3] The encyclopedic part of the Book of Jin classified the appearance of the Romans as being genuinely Xirong, a barbaric people who lived west of the Zhou dynasty, however, the characteristics attributed to Daqin tend to be more positive than the others, saying that their people when they reached adulthood looked like the Chinese, they used glass on the walls of their houses (considered a luxury item in the Tang dynasty), their tiles were covered with coral, their "king" had 5 palaces, all huge, and all far from each other, just as what was heard in one palace took time to reach another and so on.

[17] Starting in the 1st century BC with Virgil, Horace, and Strabo, Roman histories offer only vague accounts of China and the silk-producing Seres of the distant east.

The 2nd-century historian Florus seems to have conflated the Seres with peoples of India, or at least noted that their skin complexions proved that they both lived "beneath another sky" than the Romans.

The 1st-century geographer Pomponius Mela noted that their lands formed the center of the coast of an eastern ocean, flanked by India to the south and the Scythians of the northern steppe, while the historian Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330 – c. 400) wrote that the land of the Seres was enclosed by great natural walls around a river called Bautis, perhaps the Yellow River.

In his Geography, Ptolemy also provided a rough sketch of the Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea, with a port city called Cattigara lying beyond the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula) visited by a Greek sailor named Alexander.

[19] In contrast, Chinese histories offer an abundance of source material about their interactions with alleged Roman embassies and descriptions of their country.

[3] The Wenxian Tongkao written by Ma Duanlin (1245–1322) and the History of Song record that the Byzantine emperor Michael VII Parapinakēs Caesar (Mie li sha ling kai sa 滅力沙靈改撒) of Fulin (i.e. Byzantium) sent an embassy to China that arrived in 1081, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song (r.

[3][23] During the subsequent Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), an unprecedented number of Europeans started to visit and live in China, such as Marco Polo and Katarina Vilioni, and papal missionaries such as John of Montecorvino and Giovanni de Marignolli.

[24][25][26] The History of Yuan recounts how a man of Fulin named Ai-sie (transliteration of either Joshua or Joseph), initially in the service of Güyük Khan, was well-versed in Western languages and had expertise in the fields of medicine and astronomy.

[27] This convinced Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty, to offer him a position as the director of medical and astronomical boards, eventually honoring him with the title of Prince of Fulin (Chinese: 拂菻王; Fú lǐn wáng).

[36] The History of Song notes how the Byzantines made coins of either silver or gold, without holes in the middle yet with an inscription of the king's name.

For instance, people from the Parthian Empire of ancient Persia such as An Shigao were often given the surname "An" (安) derived from Anxi (安息), the Arsacid dynasty.