On the Soul

On the Soul (Greek: Περὶ Ψυχῆς, Peri Psychēs; Latin: De Anima) is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC.

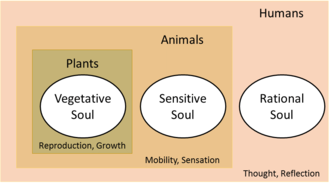

Thus plants have the capacity for nourishment and reproduction, the minimum that must be possessed by any kind of living organism.

Aristotle holds that the soul (psyche, ψυχή) is the form, or essence of any living thing; it is not a distinct substance from the body that it is in.

The treatise is near-universally abbreviated "DA", for "De anima", and books and chapters generally referred to by Roman and Arabic numerals, respectively, along with corresponding Bekker numbers.

Book I contains a summary of Aristotle's method of investigation and a dialectical determination of the nature of the soul.

From a consideration of the opinions of his predecessors, a soul, he concludes, will be that in virtue of which living things have life.

By dividing substance into its three meanings (matter, form, and what is composed of both), he shows that the soul must be the first actuality of a natural, organized body.

Some animals in addition have other senses (sight, hearing, taste), and some have more subtle versions of each (the ability to distinguish objects in a complex way, beyond mere pleasure and pain.)

The possible intellect is an "unscribed tablet" and the store-house of all concepts, i.e. universal ideas like "triangle", "tree", "man", "red", etc.

For example, when a student learns a proof for the Pythagorean theorem, his agent intellect abstracts the intelligibility of all the images his eye senses (and that are a result of the translation by imagination of sense perceptions into immaterial phantasmata), i.e. the triangles and squares in the diagrams, and stores the concepts that make up the proof in his possible intellect.

The argument for the existence of the agent intellect in Chapter V perhaps due to its concision has been interpreted in a variety of ways.

One standard scholastic interpretation is given in the Commentary on De anima begun by Thomas Aquinas.

[citation needed] One argument for its immaterial existence runs like this: if the mind were material, then it would have to possess a corresponding thinking-organ.

Perhaps the most important but obscure argument in the whole book is Aristotle's demonstration of the immortality of the thinking part of the human soul, also in Chapter V. Taking a premise from his Physics, that as a thing acts, so it is, he argues that since the active principle in our mind acts with no bodily organ, it can exist without the body.

As to what mind Aristotle is referring to in Chapter V (i.e. divine, human, or a kind of world soul), has represented a hot topic of discussion for centuries.

The most likely is probably the interpretation of Alexander of Aphrodisias, likening Aristotle's immortal mind to an impersonal activity, ultimately represented by God.

It is likely based on a Greek original which is no longer extant, and which was further syncretised in the heterogeneous process of adoption into early Arabic literature.

Averroes (d. 1198) used two Arabic translations, mostly relying on the one by Ishaq ibn Hunayn, but occasionally quoting the older one as an alternative.

Zerahiah ben Shealtiel Ḥen translated Aristotle's De anima from Arabic into Hebrew in 1284.

The manuscript was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

Another member of the family κ: Gc W Hc Nc Jd Oc Zc Vc Wc f Nd Td.

The manuscript was cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, and Apelt in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[8] The manuscript was not cited by Trendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[10] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in rheir critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[12] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, or Ross in their critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[13] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[14] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

[15] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.

The codex includes commentary on the treatise by Simplicius of Cilicia and Sophonias and paraphrases by Themistius (fourteenth century).

[16] The manuscript was not cited by Tiendelenburg, Torstrik, Biehl, Apelt, and Ross in his critical editions of the treatise On the Soul.