De re metallica

In the Middle Ages these people held the same leading role as the master builders of the great cathedrals, or perhaps also alchemists.

The most important works in this genre were, however, the twelve books of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, published in 1556.

After Joachimsthal, he spent the rest of his life in Chemnitz in Saxony, another prominent mining town in the Ore Mountains.

The book was greatly influential, and for more than a century after it was published, De Re Metallica remained a standard treatise used throughout Europe.

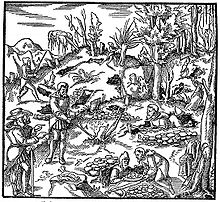

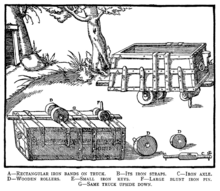

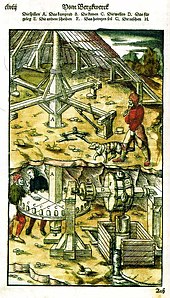

The 292 superb woodcut illustrations and the detailed descriptions of machinery made it a practical reference for those wishing to replicate the latest in mining technology.

[2] The drawings from which the woodcuts were made were done by an artist in Joachimsthal named Blasius Weffring or Basilius Wefring.

The woodcuts were then prepared in the Froben publishing house by Hans Rudolf Manuel Deutsch and Zacharias Specklin.

The translation is notable not only for its clarity of language, but for the extensive footnotes, which detail the classical references to mining and metals.

Subsequent translations into other languages, including German, owe much to the Hoover translations, as their footnotes detail their difficulties with Agricola's invention of several hundred Latin expressions to cover Medieval German mining and milling terms that were unknown to classical Latin.

It also has numerous woodcuts that provide annotated diagrams illustrating equipment and processes described in the text.

Agricola addresses the book to prominent German aristocrats, the most important of whom were Maurice, Elector of Saxony and his brother Augustus, who were his main patrons.

Agricola does not reject the idea of alchemy, but notes that alchemical writings are obscure and that we do not read of any of the masters who became rich.

Finally, he again directly addresses his audience of German princes, explaining the wealth that can be gained from this art.

He explains that mining and prospecting are not just a matter of luck and hard work; there is specialized knowledge that must be learned.

A miner should have knowledge of philosophy, medicine, astronomy, surveying, arithmetic, architecture, drawing and law, though few are masters of the whole craft and most are specialists.

The arguments range from philosophical objections to gold and silver as being intrinsically worthless, to the danger of mining to its workers and its destruction of the areas in which it is carried out.

The dangers to miners are dismissed, noting that most deaths and injuries are caused by carelessness, and other occupations are hazardous too.

The loss of food from the forests destroyed can be replaced by purchase from profits, and metals have been placed underground by God and man is right to extract and use them.

The actual mineworking varies with the hardness of the rock, the softest is worked with a pick and requires shoring with wood, the hardest is usually broken with fire.

The book concludes with a long treatise on surveying, showing the instruments required and techniques for determining the course of veins and tunnels.

Agricola also describes several designs of piston force pumps, which are either man or animal-powered, or powered by water wheels.

Designs of wind scoop for ventilating shafts or forced air using fans or bellows are also described.

The prepared ore is wrapped in paper, placed on a scorifier and then placed under a muffle covered in burning charcoal in the furnace.

Finally detailed arithmetical examples show the calculations needed to give the yield from the assay.

Several different types of machinery for crushing ore and washing it are illustrated and different techniques for different metals and different regions are described.

This describes the preparation of what Agricola calls "juices": salt, soda, nitre, alum, vitriol, saltpetre, sulphur and bitumen.

Prof. Philippus Bechius (1521–1560), a friend of Agricola, translated De re metallica libri XII into German.

[7] Although Agricola died in 1555, the publication was delayed until the completion of the extensive and detailed woodcuts one year after his death.

No expense was spared for this edition: in its typography, fine paper and binding, quality of reproduced images, and vellum covers, the publisher attempted to match the extraordinarily high standards of the sixteenth-century original.

Subsequent translations into other languages, including German, owe much to the Hoover translations, as their footnotes detail their difficulties with Agricola's invention of several hundred Latin expressions to cover Medieval German mining and milling terms unknown to classical Latin.