Decay chain

In nuclear science a decay chain refers to the predictable series of radioactive disintegrations undergone by the nuclei of certain unstable chemical elements.

This chain of decays always terminates in a stable isotope, whose nucleus no longer has the surplus of energy necessary to produce another emission of radiation.

The time required for an atom of a parent isotope to decay into its daughter is fundamentally unpredictable and varies widely.

From ten seconds to 20 minutes after the beginning of the universe the earliest condensation of light atoms was responsible for the manufacture of the four lightest elements.

So far as is known, all heavier elements came into being starting around 100 million years later, in a second phase of nucleosynthesis that commenced with the birth of the first stars.

[1] The nuclear furnaces that power stellar evolution were necessary to create large quantities of all elements heavier than helium, and the r- and s-processes of neutron capture that occur in stellar cores are thought to have created all such elements up to iron and nickel (atomic numbers 26 and 28).

The extreme conditions that attend supernovae explosions are capable of creating the elements between oxygen and rubidium (i.e., atomic numbers 8 through 37).

Most of the isotopes of each chemical element present in the Earth today were formed by such processes no later than the time of our planet's condensation from the solar protoplanetary disc, around 4.5 billion years ago.

The exceptions to these so-called primordial elements are those that have resulted from the radioactive disintegration of unstable parent nuclei as they progress down one of several decay chains, each of which terminates with the production of one of the 251 stable isotopes known to exist.

Aside from cosmic or stellar nucleosynthesis, and decay chains the only other ways of producing a chemical element rely on atomic weapons, nuclear reactors (natural or manmade) or the laborious atom-by-atom assembly of nuclei with particle accelerators.

For some isotopes with a relatively low n/p ratio, there is an inverse beta decay, by which a proton is transformed into a neutron, thus moving towards a stable isotope; however, since fission almost always produces products which are neutron heavy, positron emission or electron capture are rare compared to electron emission.

Thus they again take their places in the chain: plutonium-239, used in nuclear weapons, is the major example, decaying to uranium-235 via alpha emission with a half-life 24,500 years.

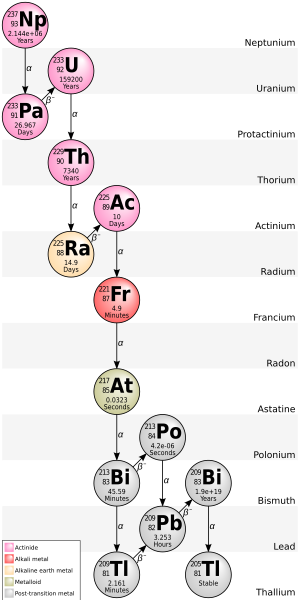

Due to the relatively short half-life of its starting isotope neptunium-237 (2.14 million years), the fourth chain, the neptunium series with A = 4n + 1, is already extinct in nature, except for the final rate-limiting step, decay of bismuth-209.

Traces of 237Np and its decay products do occur in nature, however, as a result of neutron capture in uranium ore.[8] The ending isotope of this chain is now known to be thallium-205.

Some older sources give the final isotope as bismuth-209, but in 2003 it was discovered that it is very slightly radioactive, with a half-life of 2.01×1019 years.

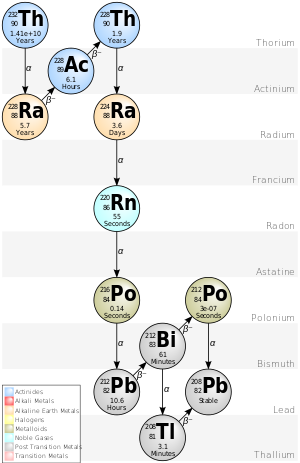

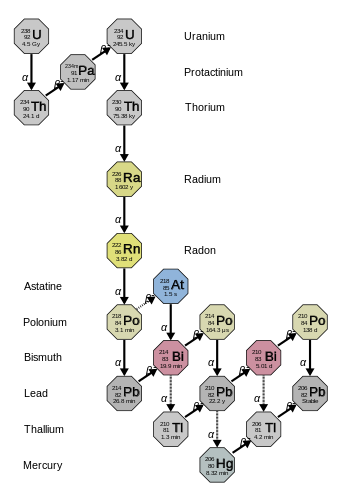

The three naturally-occurring actinide alpha decay chains given below—thorium, uranium/radium (from uranium-238), and actinium (from uranium-235)—each ends with its own specific lead isotope (lead-208, lead-206, and lead-207 respectively).

Beginning with naturally occurring thorium-232, this series includes the following elements: actinium, bismuth, lead, polonium, radium, radon and thallium.

Plutonium-244 (which appears several steps above thorium-232 in this chain if one extends it to the transuranics) was present in the early Solar System,[6] and is just long-lived enough that it should still survive in trace quantities today,[15] though it is uncertain if it has been detected.

Some of the other isotopes have been detected in nature, originating from trace quantities of 237Np produced by the (n,2n) knockout reaction in primordial 238U.

The following elements are also present in it, at least transiently, as decay products of the neptunium: actinium, astatine, bismuth, francium, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, thorium, and uranium.

Another unique trait of this decay sequence is that it ends in thallium (practically speaking, bismuth) rather than lead.

Beginning with naturally occurring uranium-238, this series includes the following elements: astatine, bismuth, lead, mercury, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, and thorium.

Beginning with the naturally-occurring isotope uranium-235, this decay series includes the following elements: actinium, astatine, bismuth, francium, lead, polonium, protactinium, radium, radon, thallium, and thorium.