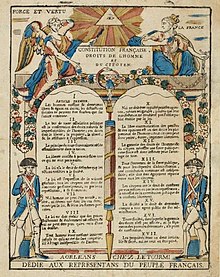

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a significant impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.

[4][5] In August 1789, Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

[2][6] The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France.

Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives based on a 24-article draft proposed by the sixth bureau[clarify],[7][8] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé.

Improvements in education and literacy over the course of the 18th century meant larger audiences for newspapers and journals, with Masonic lodges, coffee houses and reading clubs providing areas where people could debate and discuss ideas.

The emergence of this "public sphere" led to Paris replacing Versailles as the cultural and intellectual centre, leaving the Court isolated and less able to influence opinion.

When presented to the legislative committee on 11 July, it was rejected by pragmatists such as Jean Joseph Mounier, President of the Assembly, who feared creating expectations that could not be satisfied.

[13] Conservatives like Gérard de Lally-Tollendal wanted a bicameral system, with an upper house appointed by the king, who would have the right of veto.

On 10 September, the majority led by Sieyès and Talleyrand rejected this in favour of a single assembly, while Louis XVI retained only a "suspensive veto"; this meant he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it.

With these questions settled, a new committee was convened to agree on a constitution; the most controversial remaining issue was citizenship, itself linked to the debate on the balance between individual rights and obligations.

[15] French historian Georges Lefebvre argues that combined with the elimination of privilege and feudalism, it "highlighted equality in a way the (American Declaration of Independence) did not".

[16] More importantly, the two differed in intent; Jefferson saw the US Constitution and Bill of Rights as fixing the political system at a specific point in time, claiming they 'contained no original thought...but expressed the American mind' at that stage.

[20] The Declaration is introduced by a preamble describing the fundamental characteristics of the rights, which are qualified as "natural, unalienable and sacred" and "simple and incontestable principles" on which citizens could base their demands.

It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end to feudalism and to exemptions from taxation, freedom, and equal rights for all "Men" and access to public office based on talent.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Active citizenship was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants.

[citation needed] These omitted groups included women, the poor, domestic servants, enslaved people, children, and foreigners.

As the General Assembly voted upon these measures, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the new French Republic (1792–1804).

Olympe de Gouges penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality.

As players in the French Revolution, women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political power.

[32] In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d'Aelders unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.

The vast amount of personal freedom given to citizens by the document created a situation where homosexuality was decriminalized by the French Penal Code of 1791, which covered felonies; the law simply failed to mention sodomy as a crime, and thus no one could be prosecuted for it.