Demographic history of Scotland

Changes in the extent of woodland indicates that the Roman invasions from the first century AD had a negative impact on the native population.

Roughly half lived north of the River Tay and perhaps 10 per cent in the burghs that grew up in the later medieval period.

Inflation in prices, indicating greater demand, suggests that the population continued to grow until the late sixteenth century, when it probably levelled off.

Despite industrial expansion there were insufficient jobs and between the mid-nineteenth century and the Great Depression about two million Scots emigrated to North America and Australia, and another 750,000 to England.

At times during the last interglacial period (130,000– 70,000 BC) Europe had a climate warmer than today's, and early humans may have made their way to what is now Scotland, though archaeologists have found no traces of this.

[3] Numerous other sites found around Scotland build up a picture of highly mobile boat-using people making tools from bone, stone and antlers, probably with a very low density of population.

[4] Neolithic farming brought permanent settlements, such as the stone house at Knap of Howar on Papa Westray dating from 3500 BC, and greater concentrations of population.

[8] Extensive analyses of Black Loch in Fife indicate that arable land spread at the expense of forest from about 2000 BCuntil the time of the Roman advance into lowland Scotland in the first century AD, suggesting an expanding settled population.

Thereafter, there was regrowth of birch, oak and hazel for some 500 years, suggesting that the Roman invasions had a negative impact on the native population.

[10] It is likely that the fifth and sixth centuries saw higher mortality rates due to the appearance of bubonic plague, which may have reduced the population.

This would have meant a relatively low ratio of available workers to the number of mouths to feed, which in turn would have made it difficult to produce a surplus that would allow demographic growth and the development of more complex societies.

More significant was a series of poor harvests that affected Scotland and most of Europe in the early fourteenth century and widespread famines in 1315–16 and in the later 1330s.

[16] Compared with the distribution of population after the later Clearances and the Industrial Revolution, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the River Tay.

[17]Price inflation, which generally reflects growing demand for food, suggests that the population was probably still expanding in the first half of the sixteenth century.

The invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century, but population probably expanded in the Lowlands in the period of stability that followed the Restoration in 1660.

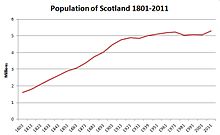

[25] The first reliable figure for the national population is from the census conducted by the Reverend Alexander Webster in 1755, which showed the inhabitants of Scotland as 1,265,380 persons.

[30] Edinburgh doubled in size in the century after 1540, particularly after the plague of 1580, with most of its population probably coming from a growing reservoir in the surrounding countryside.

Thousands of cottars and tenant farmers migrated from farms and smallholdings to the new industrial centres of Glasgow, Edinburgh and northern England.

[34] Particularly after the end of the boom created by the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1790–1815), Highland landlords needed cash to maintain their position in London society.

Particularly in the north and west Highlands, estates offered alternative accommodation in newly established crofting communities, with the intention that the resettled tenants worked in fishing or the kelp industry.

[45] With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the First World War, of whom 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.

[48] While emigration began to tail off in England and Wales after the First World War,[49] it continued apace in Scotland, with 400,000 Scots, 10 per cent of the population, estimated to have left the country between 1921 and 1931.

[50] When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s there were no easily available jobs in the US and Canada, and emigration fell to less than 50,000 a year, bringing to an end the period of mass migrations that had opened in the mid-eighteenth century.

[52] In the early part of the twenty-first century Scotland saw a rise in its population to 5,313,600 (its highest ever recorded) at the 2011 census.