Great Famine (Ireland)

[18][19] Initial limited but constructive government actions to alleviate famine distress were ended by a new Whig administration in London, which pursued a laissez-faire economic doctrine, but also because some in power believed in divine providence or that the Irish lacked moral character,[20][21] with aid only resuming to some degree later.

Additionally, the famine indirectly resulted in tens of thousands of households being evicted, exacerbated by a provision forbidding access to workhouse aid while in possession of more than one-quarter acre of land.

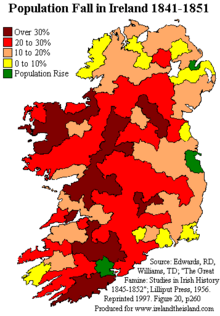

The famine and its effects permanently changed the island's demographic, political, and cultural landscape, producing an estimated 2 million refugees and spurring a century-long population decline.

[43] In February 1845, Devon reported: It would be impossible adequately to describe the privations which they [the Irish labourer and his family] habitually and silently endure ... in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water ... their cabins are seldom a protection against the weather ... a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury ... and nearly in all their pig and a manure heap constitute their only property.

[44]The Commissioners concluded they could not "forbear expressing our strong sense of the patient endurance which the labouring classes have exhibited under sufferings greater, we believe, than the people of any other country in Europe have to sustain".

[62] American plant pathologist William C. Paddock[63] posited that the blight was transported via potatoes being carried to feed passengers on clipper ships sailing from America to Ireland.

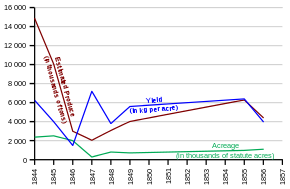

[66] The Mansion House Committee in Dublin, to which hundreds of letters were directed from all over Ireland, claimed on 19 November 1845 to have ascertained beyond the shadow of a doubt that "considerably more than one-third of the entire of the potato crop ... has been already destroyed".

[90] Confronted by widespread crop failure in November 1845, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, purchased £100,000 worth of maize and cornmeal secretly from America[91] with Baring Brothers initially acting as his agents.

[94] In October 1845, Peel moved to repeal the Corn Laws—tariffs on grain which kept the price of bread high—but the issue split his party and he had insufficient support from his own colleagues to push the measure through.

[103]In January 1847, the government abandoned its policy of noninterference, realising that it had failed, and turned to a mixture of "indoor" and "outdoor" direct relief; the former administered in workhouses through the Irish Poor Laws, the latter through soup kitchens.

The costs of the Poor Law fell primarily on the local landlords, some of whom in turn attempted to reduce their liability by evicting their tenants[101] or providing some relief through the conversionist practice of Souperism.

In February 1847, Trevelyan ordered Royal Navy surgeons dispatched to provide medical care for those suffering from illnesses that accompanied starvation, distribute medicines that were in short supply, and assist in proper, sanitary burials for the deceased.

From one milling establishment I have last night seen not less than fifty dray loads of meal moving on to Drogheda, thence to go to feed the foreigner, leaving starvation and death the sure and certain fate of the toil and sweat that raised this food.

The appalling character of the crisis renders delicacy but criminal and imperatively calls for the timely and explicit notice of principles that will not fail to prove terrible arms in the hands of a neglected, abandoned starving people.

[119] Grain imports increased after the spring of 1847 and much of the debate "has been conducted within narrow parameters," focusing "almost exclusively on national estimates with little attempt to disaggregate the data by region or by product.

[c] According to legend,[124][125][126] Sultan Abdülmecid I of the Ottoman Empire originally offered to send £10,000[d] but was asked either by British diplomats or his own ministers to reduce it to £1,000[e] to avoid donating more than the Queen.

"[149] In 1847, Bishop of Meath, Thomas Nulty, described his personal recollection of the evictions in a pastoral letter to his clergy: Seven hundred human beings were driven from their homes in one day and set adrift on the world, to gratify the caprice of one who, before God and man, probably deserved less consideration than the last and least of them ...

The landed proprietors in a circle all around—and for many miles in every direction—warned their tenantry, with threats of their direct vengeance, against the humanity of extending to any of them the hospitality of a single night's shelter ... and in little more than three years, nearly a fourth of them lay quietly in their graves.

[165] Overcrowded, poorly maintained, and badly provisioned vessels known as coffin ships sailed from small, unregulated harbours in the West of Ireland in contravention of British safety requirements, and mortality rates were high.

[167] Unlike the United States, Canada could not close its ports to Irish ships because it was part of the British Empire, so emigrants could obtain cheap passage in returning empty lumber holds.

[191] Social dislocation—the congregation of the hungry at soup kitchens, food depots, and overcrowded workhouses—created conditions that were ideal for spreading infectious diseases such as typhus, typhoid, and relapsing fever.

According to Peter Gray in his book The Irish Famine, the government spent £7 million for relief in Ireland between 1845 and 1850, "representing less than half of one per cent of the British gross national product over five years.

[205] Mokyr argues that, despite its formal integration into the United Kingdom, Ireland was effectively a foreign country to the British, who were therefore unwilling to spend resources that could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

James Anthony Froude wrote that "England governed Ireland for what she deemed her own interest, making her calculations on the gross balance of her trade ledgers, and leaving moral obligations aside, as if right and wrong had been blotted out of the statute book of the Universe.

But in 1997, at a commemoration event in County Cork, the actor Gabriel Byrne read out a message by Prime Minister Tony Blair that acknowledged the inadequacy of the government response.

[209] He argued that "genocide includes murderous intent, and it must be said that not even the most bigoted and racist commentators of the day sought the extermination of the Irish", and he also stated that most people in Whitehall "hoped for better times for Ireland".

[223] Nat Hill, director of research at Genocide Watch, has stated that "While the potato famine may not fit perfectly into the legal and political definitions of 'genocide', it should be given equal consideration in history as an egregious crime against humanity".

[225][226] Designed by Irish artist John Behan, the memorial consists of a bronze sculpture of a coffin ship with skeletons interwoven through the rigging symbolising the many emigrants that did not survive the journey across the ocean to Britain, America and elsewhere.

[231] Kindred Spirits, a large stainless steel sculpture of nine eagle feathers by artist Alex Pentek was erected in 2017 in the Irish town of Midleton, County Cork, to thank the Choctaw people for its financial assistance during the famine.

[232][233] An annual Great Famine walk from Doolough to Louisburgh, County Mayo was inaugurated in 1988 and has been led by such notable personalities as Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa and representatives of the Choctaw nation of Oklahoma.