Armenian genocide denial

Scholars argue that Armenian genocide denial has set the tone for the government's attitude towards minorities, and has contributed to the ongoing violence against Kurds in Turkey.

[10][11] The Ottoman Empire effectively treated Armenians and other non-Muslims as second-class citizens under Islamic rule, even after the nineteenth-century Tanzimat reforms intended to equalize their status.

[14][15][16] The Ottoman authorities denied any responsibility for these massacres, accusing Western powers of meddling and Armenians of provocation, while presenting Muslims as the main victims and failing to punish the perpetrators.

[22] Hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees fled to Anatolia as a result of the wars; many were resettled in the Armenian-populated eastern provinces and harbored resentment against Christians.

[35] The defense of Van served as a pretext for anti-Armenian actions at the time and remains a crucial element in works that seek to deny or justify the genocide.

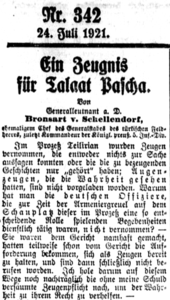

[38] The leaders of the CUP ordered the deportations, with interior minister Talat Pasha, aware that he was sending the Armenians to their deaths, taking a leading role.

[60][61][62] There was significant continuity between the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey, and the Republican People's Party was the successor of the Committee of Union and Progress that carried out the genocide.

"[80][81] Historian Erik-Jan Zürcher argues that, since the Turkish nationalist movement depended on the support of a broad coalition of actors that benefitted from the genocide, it was impossible to break with the past.

[95][96] During his fieldwork in an Anatolian village in the 1980s, anthropologist Sam Kaplan found that "a visceral fear of Armenians returning ... and reclaiming their lands still gripped local imagination".

[97] An edict of the Ottoman government banned foreigners from taking photographs of Armenian refugees or the corpses that accumulated on the sides of the roads on which death marches were carried out.

[102][101] On 5 January 1916, Enver Pasha ordered all place names of Greek, Armenian, or Bulgarian origin to be changed, a policy fully implemented in the later republic, continuing into the 1980s.

Retired diplomats were recruited to write denialist works, completed without professional methodology or ethical standards and based on cherry-picking archival information favorable to Turks and unfavorable to Armenians.

"[152] The Turkish state and most of society have engaged in similar silencing regarding other ethnic persecutions and human rights violations in the Ottoman Empire and Republican Turkey against Greeks, Assyrians, Kurds, Jews and Alevis.

[166][167] Over time, and especially since the 2016 failed coup, the AKP government became increasingly authoritarian; political repression and censorship has made it more difficult to discuss controversial topics such as the Armenian genocide.

"[6] Central to Turkey's ability to deny the genocide and counter its recognition is the country's strategic position in the Middle East, Cold War alliance with the West, and membership of NATO.

[188] According to sociologist Levon Chorbajian, Turkey's "modus operandi remains consistent throughout and seeks maximalist positions, offers no compromise though sometimes hints at it, and employs intimidation and threats.

[191] Akçam stated in 2020 that Turkey has definitively lost the information war over the Armenian genocide on both the academic and diplomatic fronts, its official narrative being treated like ordinary denialism.

[199] In March 2006, Turkish nationalist groups organized two rallies in Berlin intended to commemorate "the murder of Talat Pasha" and protest "the lie of genocide."

"[204][205] In interwar Turkey, prominent American diplomats like Mark L. Bristol and Joseph Grew endorsed the Turkish nationalist view that the Armenian genocide was a war against the forces of imperialism.

[210] Şükrü Elekdağ, Turkish ambassador to the United States from 1979 to 1989, worked aggressively to counter the trend of Armenian genocide recognition by courting academics, business interests, and Jewish groups.

[216] Human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson charged that around 2000, "genocide denial had entrenched itself in the Eastern Department [of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)] ... to such an extent that it was briefing ministers with a bare-faced disregard for readily ascertainable facts", such as its own records from the time.

[224] Until the twenty-first century, Ottoman and Turkish studies marginalized the killings of Armenians, which many academics portrayed as a wartime measure justified by emergency and avoided discussing in depth.

[232][233][210] On 19 May 1985, The New York Times and The Washington Post ran an advertisement from the Assembly of Turkish American Associations[234] in which 69 academics—most of the professors of Ottoman history working in the United States at the time—called on Congress not to adopt the resolution on the Armenian genocide.

[243][244] TCA has also provided financial support to several authors including McCarthy, Michael Gunter, Yücel Güçlü, and Edward J. Erickson for writing books that deny the Armenian genocide.

The court ruled that while Lewis has the right to his views, their expression harmed a third party and that "it is only by hiding elements which go against his thesis that the defendant was able to state there was no 'serious proof' of the Armenian Genocide".

[313] Akçam says that genocide denial "rationaliz[es] the violent persecution of religious and ethnic minorities" and desensitizes the population to future episodes of mass violence.

Historian Talin Suciyan states that the Armenian genocide and its denial "led to a series of other policies that perpetuated the process by liquidating their properties, silencing and marginalising the survivors, and normalising all forms of violence against them".

[318] According to an article in the Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, "[d]enial prevents healing of the wounds inflicted by genocide, and constitutes an attack on the collective identity and national cultural continuity of the victimized people".

[328] Bloxham asserts that since "denial has always been accompanied by rhetoric of Armenian treachery, aggression, criminality, and territorial ambition, it actually enunciates an ongoing if latent threat of Turkish 'revenge'.

[338] Cheterian argues that the "unresolved historic legacy of the 1915 genocide" helped cause the Karabakh conflict and prevent its resolution, while "the ultimate crime itself continues to serve simultaneously as a model and as a threat, as well as a source of existential fear".