Baseball color line

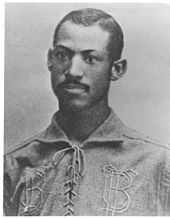

In 1887, Anson made a successful threat by telegram before an exhibition game against the Newark Little Giants of the International League that it must not play its two black players, Fleet Walker and pitcher George Stovey.

"[5] On the afternoon of the International League vote, Anson's Chicago team played the game in Newark alluded to above, with Stovey and the apparently injured Walker sitting out.

In September 1887, eight members of the St. Louis Browns of the then-major American Association (who would ultimately change their nickname to the current St. Louis Cardinals) staged a mutiny during a road trip, refusing to play a game against the New York Cuban Giants, the first all-black professional baseball club, and citing both racial and practical reasons: that the players were banged up and wanted to rest so as to not lose their hold on first place.

Besides White's single game in 1879, the only black players in major league baseball for around 75 years were Fleet Walker and his brother Weldy, both in 1884 with Toledo.

[11] While professional baseball was formally regarded as a strictly white-men-only affair, the racial color bar was directed against black players exclusively.

[13] On May 28, 1916, Canadian-American Jimmy Claxton temporarily broke the professional baseball color barrier when he played two games for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League.

The only serious attempt to break the color line during Landis's tenure came in 1942, when Bill Veeck tried to buy the then-moribund Philadelphia Phillies and stock them with Negro league stars.

[19] Joseph Thomas Moore wrote in his 1988 biography of Doby, "Bill Veeck planned to buy the Philadelphia Phillies with the as yet unannounced intention of breaking that color line.

Rickey, along with Gus Greenlee who was the owner of the original Pittsburgh Crawfords, created the United States League (USL) as a method to scout black players specifically to break the color line.

[23] One of the many origins of the Civil rights movement and other efforts at integration in America stemmed from the treatment black veterans received at home versus overseas as well as the juxtaposition of fighting for democracy in Europe while segregation still existed in the United States.

[26] As a writer for the Daily Worker, Lester Rodney utilized his role in the media to help integrate Major League Baseball by pressuring the establishment.

[27] By the late 1930s, MLB managers including Burleigh Grimes had already admitted to sportswriters at the Daily Worker that black ballplayers were of, "Big League Quality," but no one wanted to put their career in jeopardy by allowing that statement on an official record.

[27] Despite general support of this sentiment from many other managers and players like Bill McKechnie, Doc Prothro, Leo Durocher, Ray Blades, Casey Stengel, Pie Traynor, Gabby Hartnett, Ernie Lombardi, Mel Ott, Carl Hubbell, Johnny Vander Meer, Bucky Walters, Al Simmons, Hans Wagner, Paul Waner, Lloyd Waner, Arky Vaughan, Augie Galan, Dizzy Dean, Paul Dean (baseball), and Pepper Martin, all of them went along with the MLB’s official position that baseball would be integrated once the fans were ready.

[27] Although his contributions to the breaking of the color line were downplayed at the time due to his communist ties, fellow sportswriting activists such as Wendell Smith (sportswriter) commended Rodney's efforts at integrating the sport, reportedly writing to Rodney: "I take this opportunity to congratulate you and the Daily Worker for the way you have joined with us on the current series concerning Negro players in the major leagues, as well as all your past great efforts in this respect...I wish you the best of luck and admire you and your liberal attitude.

[28][29][30] Robeson was a part of the December 1943 meeting with MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to appeal for the breaking of the color line in professional baseball.

[28][30] Bill Mardo, a writer for the Daily Worker and activist who helped integrate professional baseball, reportedly admonished Robinson for his lack of gratitude towards Robeson's efforts to break the color line and concluded at the time that the Brooklyn Dodger's, "memory is short indeed.

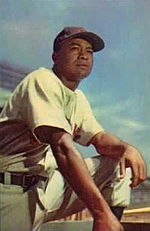

"[30] The color line was breached when Rickey, with the support of new commissioner Happy Chandler, signed Jackie Robinson in October 1945, intending him to play for the Dodgers.

Jackie Robinson and Johnny Wright were assigned to Montreal, but also that season Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella became members of the Nashua Dodgers in the class-B New England League.

Peeples went hitless in two games played and four at bats on April 9–10, 1954, was demoted one classification to the Jacksonville Braves of the Sally League, and the SA reverted to white-only status.

In April 1945, the Red Sox refused to consider signing Jackie Robinson (and future Boston Braves outfielder Sam Jethroe) after giving him a brief tryout at Fenway Park.

[36] The tryout, however, was a farce chiefly designed to assuage the desegregationist sensibilities of Boston City Councilman Isadore H. Y. Muchnick, who threatened to revoke the team's exemption from Sunday blue laws.

[39] On April 7, 1959, during spring training, Yawkey and general manager Bucky Harris were named in a lawsuit charging them with discrimination and the deliberate barring of black players from the Red Sox.

[40] The NAACP issued charges of "following an anti-Negro policy", and the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination announced a public hearing on racial bias against the Red Sox.

[41] Thus, the Red Sox were forced to integrate, becoming the last pre-expansion major-league team to do so when Harris promoted Pumpsie Green from Boston's AAA farm club.

On July 21, Green debuted for the team as a pinch runner, and would be joined later that season by Earl Wilson, the second black player to play for the Red Sox.

[43] Listed chronologically † The Sporting News contemporaneously reported it as "the first all-Negro starting lineup"; later sources state Black and Latino or "all-minority".

[50] Prior to the next season, the Official Baseball Guide published by The Sporting News stated, "he [Banks] became the major leagues' first black manager—but only for a day".