Jackie Robinson

Following his college career, Robinson was drafted for service during World War II but was court-martialed for refusing to sit at the back of a segregated Army bus, eventually being honorably discharged.

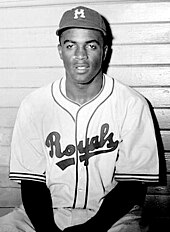

Afterwards, he signed with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro leagues, where he caught the eye of Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who thought he would be the perfect candidate for breaking the color line in MLB.

[14] In late January 1937, the Pasadena Star-News newspaper reported that Robinson "for two years has been the outstanding athlete at Muir, starring in football, basketball, track, baseball, and tennis.

[11][26] After graduating from PJC in spring 1939,[27] Robinson enrolled at UCLA, where he became the school's first athlete to win varsity letters in four sports: baseball, basketball, football, and track.

[40][42] After a short season, Robinson returned to California in December 1941 to pursue a career as running back for the Los Angeles Bulldogs of the Pacific Coast Football League.

[43] By that time, however, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had taken place, which drew the United States into World War II and ended Robinson's nascent football career.

[47] After protests by heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis (then stationed at Fort Riley) and with the help of Truman Gibson (then an assistant civilian aide to the Secretary of War),[48] the men were accepted into OCS.

[63][64] Although his teams were outmatched by opponents, Robinson was respected as a disciplinarian coach,[51] and drew the admiration of, among others, Langston University basketball player Marques Haynes, a future member of the Harlem Globetrotters.

Rickey selected Robinson from a list of promising black players and interviewed him for possible assignment to Brooklyn's International League farm club, the Montreal Royals.

He was not allowed to stay with his white teammates at the team hotel, and instead lodged at the home of Joe and Dufferin Harris, a politically active African-American couple who introduced the Robinsons to civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune.

[1] In the fall of 1946, following the baseball season, Robinson returned home to California and briefly played professional basketball for the short-lived Los Angeles Red Devils.

[80] Robinson made his debut as a Dodger wearing uniform number 42 on April 11, 1947, in a preseason exhibition game against the New York Yankees at Ebbets Field with 24,237 in attendance.

[144] Robinson also talked frequently with Larry Doby, who endured his own hardships since becoming the first black player in the American League with the Cleveland Indians, as the two spoke to each other via telephone throughout the season.

[150] The Dodgers briefly moved into first place in the National League in late August 1948, but they ultimately finished third as the Braves went on to win the pennant and lose to the Cleveland Indians in the World Series.

In July, he was called to testify before the United States House of Representatives' Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) concerning statements made that April by black athlete and actor Paul Robeson.

[160] The project had been previously delayed when the film's producers refused to accede to demands of two Hollywood studios that the movie include scenes of Robinson being tutored in baseball by a white man.

[161] The New York Times wrote that Robinson, "doing that rare thing of playing himself in the picture's leading role, displays a calm assurance and composure that might be envied by many a Hollywood star.

Robinson was disappointed at the turn of events and wrote a sympathetic letter to Rickey, whom he considered a father figure, stating, "Regardless of what happens to me in the future, it all can be placed on what you have done and, believe me, I appreciate it.

[173] That year, on the television show Youth Wants to Know, Robinson challenged the Yankees' general manager, George Weiss, on the racial record of his team, which had yet to sign a black player.

[176] In 1953, Robinson had 109 runs, a .329 batting average, and 17 steals, leading the Dodgers to another National League pennant (and another World Series loss to the Yankees, this time in six games).

After World War II, several other forces were also leading the country toward increased equality for blacks, including their accelerated migration to the North, where their political clout grew, and President Harry Truman's desegregation of the military in 1948.

[189] Robinson's breaking of the baseball color line and his professional success symbolized these broader changes and demonstrated that the fight for equality was more than simply a political matter.

"[190] According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Robinson's "efforts were a monumental step in the civil-rights revolution in America ... [His] accomplishments allowed black and white Americans to be more respectful and open to one another and more appreciative of everyone's abilities.

[193] Robinson's career is generally considered to mark the beginning of the post–"long ball" era in baseball, in which a reliance on raw power-hitting gave way to balanced offensive strategies that used footspeed to create runs through aggressive baserunning.

At a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) speech in Greenville, South Carolina, Robinson urged "complete freedom" and encouraged black citizens to vote and to protest their second-class citizenship.

He identified himself as a political independent,[236][237] although he held conservative opinions on several issues, including the Vietnam War (he once wrote to Martin Luther King Jr. to defend the Johnson Administration's military policy).

[188] Robinson protested against the major leagues' ongoing lack of minority managers and central office personnel, and he turned down an invitation to appear in an old-timers' game at Yankee Stadium in 1969.

[244][245] He gratefully accepted a plaque honoring the twenty-fifth anniversary of his MLB debut, but also commented, "I'm going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a black face managing in baseball.

[258][260] Tens of thousands of people lined the subsequent procession route to Robinson's interment site at Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn, where he was buried next to his son Jackie and mother-in-law Zellee Isum.

[290] Ultimately, more than 200 players wore number 42, including the entire rosters of the Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Mets, Houston Astros, Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, Milwaukee Brewers, and Pittsburgh Pirates.