Desert locust

In some years, they may thus form locust plagues, invading new areas, where they may consume all vegetation including crops, and at other times, they may live unnoticed in small numbers.

The desert locust's migratory nature and capacity for rapid population growth present major challenges for control, particularly in remote semiarid areas, which characterize much of their range.

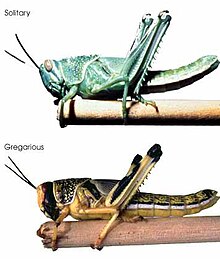

[7] Locusts differ from other grasshoppers in their ability to change from a solitary living form into gregarious, highly mobile, adult swarms and hopper bands, as their numbers and densities increase.

They exist in different states known as recessions (with low and intermediate numbers), rising to local outbreaks and regional upsurges with increasingly high densities, to plagues consisting of numerous swarms.

The major desert locust upsurge in 2004–05 caused significant crop losses in West Africa and diminished food security in the region.

[15]The change from an innocuous solitary insect to a voracious gregarious one normally follows a period of drought, when rain falls and vegetation flushes occur in major desert locust breeding locations.

Under optimal ecological and climatic conditions, several successive generations can occur, causing swarms to form and invade countries on all sides of the recession area, as far north as Spain and Russia, as far south as Nigeria and Kenya, and as far east as India and southwest Asia.

Desert locust invasions can be absolutely devastating and have serious repercussions on national and regional food security and on the livelihoods of affected rural communities, particularly the poorest.

Added to this damage is the cost of control operations implemented to protect crops, which also help to stop the spread of the invasion, which could otherwise continue for many years and over larger areas.

In the event of an invasion, control operations are of such magnitude that the products used can have serious side effects on human health, the environment, non-target organisms and biodiversity.

Correct application of the preventive strategy recommended by the FAO[23] and the use of good treatment practices that are more respectful of people and the environment can limit the negative impacts of these large-scale sprayings.

Crop and pasture losses can lead to severe food shortages and a large imbalance in food rations, large price fluctuations in markets, insufficient availability of grazing areas, the sale of animals at very low prices to meet household subsistence needs and to buy feed for remaining animals, early transhumance of herds and high tensions between transhumant herders and local farmers, and significant human migration to urban areas (sometimes fatal for the elderly, the weak and young children).

Other economic consequences can occur during harvest, as cereals can be contaminated with insect parts and downgraded to feed grains that are sold at a lower price.

[25] Early warning and preventive control is the strategy adopted by locust-affected countries in Africa and Asia to try to stop locust plagues from developing and spreading.

The teams use a variety of innovative digital devices, such as eLocust3,[29] to collect, record and transmit standardized data in real-time to their national locust centres for decision-making.

Within this system, the field data are combined with the latest satellite imagery to actively monitor rainfall, vegetation and soil moisture conditions in the locust breeding area from West Africa to India.

Models are used to estimate egg and hopper development rates and swarm trajectories (NOAA HYSPLIT) and dispersion (UK Met Office NAME).

DLIS uses a custom GIS to analyze the field data, satellite imagery, weather predictions and model results to assess the current situation and forecast the timing, scale, and location of breeding and migration up to six weeks in advance.

At present, the primary method of controlling desert locust infestations is with insecticides applied in small, concentrated doses by vehicle-mounted and aerial sprayers at ultra-low volume rates of application.

[17] Farmers often try mechanical means of killing locusts, such as digging trenches and burying hopper bands, but this is very labour-intensive and is difficult to undertake when large infestations are scattered over a wide area.

Biological control products have been under development since the late 1990s; Green Muscle and NOVACRID are based on a naturally occurring entomopathogenic fungus, Metarhizium acridum.

Green Muscle was developed under the LUBILOSA programme, which was initiated in 1989 in response to environmental concerns over the heavy use of chemical insecticides to control locusts and grasshoppers during the 1987-89 plague.

Two days of unusually heavy rains that stretched from Dakar, Senegal, to Morocco in October allowed breeding conditions to remain favourable for the next 6 months and the desert locusts rapidly increased.

The costs of fighting this upsurge have been estimated by the FAO to have exceeded US$400 million, and harvest losses were valued at up to US$2.5 billion, which had disastrous effects on food security in West Africa.

Both areas received good rains, including heavy flooding in southwest Iran (the worst in 50 years), that allowed another two generations of breeding to take place.

As a result, new swarms formed that crossed the southern Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden and invaded the Horn of Africa, specifically northeast Ethiopia and northern Somalia in June 2019.

The situation improved in Kenya and elsewhere by the summer of 2020 due to large-scale aerial control operations, made available by generous assistance from international partners.

Again, unexpected rains fell in late April and early May, this time further north that allowed substantial breeding to occur in eastern Ethiopia and northern Somalia in May and June 2021.

New swarms formed in June and July that moved to northeast Ethiopia for a generation of breeding that could not be addressed due to conflict and insecurity, which prolonged the upsurge in the Horn of Africa.

These results indicated that the formation of chiasmata is not an isolated event but the end product of an interrelated series of processes initiated at some earlier stage of meiosis.