Difference engine

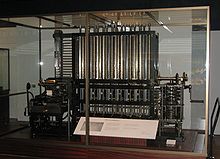

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions.

The British government was interested, since producing tables was time-consuming and expensive and they hoped the difference engine would make the task more economical.

Although Babbage's design was feasible, the metalworking techniques of the era could not economically make parts in the precision and quantity required.

Thus the implementation proved to be much more expensive and doubtful of success than the government's initial estimate.

In 1832, Babbage and Joseph Clement produced a small working model (one-seventh of the plan),[5] which operated on 6-digit numbers by second-order differences.

[9][10] Lady Byron described seeing the working prototype in 1833: "We both went to see the thinking machine (or so it seems) last Monday.

By the time the government abandoned the project in 1842,[10][12] Babbage had received and spent over £17,000 on development, which still fell short of achieving a working engine.

1 was put on display to the public at the 1862 International Exhibition in South Kensington, London.

[15][16] Inspired by Babbage's difference engine in 1834, the Swedish inventor Per Georg Scheutz built several experimental models.

In 1851, funded by the government, construction of the larger and improved (15-digit numbers and fourth-order differences) machine began, and finished in 1853.

The machine was demonstrated at the World's Fair in Paris, 1855 and then sold in 1856 to the Dudley Observatory in Albany, New York.

In 1874 the Boston Thursday Club raised a subscription for the construction of a large-scale model, which was built in 1876.

[23][26][27] Burroughs Corporation in about 1912 built a machine for the Nautical Almanac Office which was used as a difference engine of second-order.

[30] Alexander John Thompson about 1927 built integrating and differencing machine (13-digit numbers and fifth-order differences) for his table of logarithms "Logarithmetica britannica".

[31][32][33] Leslie Comrie in 1928 described how to use the Brunsviga-Dupla calculating machine as a difference engine of second-order (15-digit numbers).

[28] He also noted in 1931 that National Accounting Machine Class 3000 could be used as a difference engine of sixth-order.

[23]: 137–138 During the 1980s, Allan G. Bromley, an associate professor at the University of Sydney, Australia, studied Babbage's original drawings for the Difference and Analytical Engines at the Science Museum library in London.

[35] The conversion of the original design drawings into drawings suitable for engineering manufacturers' use revealed some minor errors in Babbage's design (possibly introduced as a protection in case the plans were stolen),[36] which had to be corrected.

Babbage intended that the Engine's results be conveyed directly to mass printing, having recognized that many errors in previous tables were not the result of human calculating mistakes but from slips in the manual typesetting process.

[7] The printer's paper output is mainly a means of checking the engine's performance.

2, which was on exhibit at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, from May 2008 to January 2016.

[44] In the Babbage design, one iteration (i.e. one full set of addition and carry operations) happens for each rotation of the main shaft.

Each iteration creates a new result, and is accomplished in four steps corresponding to four complete turns of the handle shown at the far right in the picture below.

2, finally built in 1991, can hold 8 numbers of 31 decimal digits each and can thus tabulate 7th degree polynomials to that precision.

The initial values can be calculated to any degree of accuracy; if done correctly the engine will give exact results for first N steps.

Setting 0 as the start of computation we get the simplified Maclaurin series The same method of calculating the initial values from the coefficients can be used as for polynomial functions.

The polynomial constant coefficients will now have the value The problem with the methods described above is that errors will accumulate and the series will tend to diverge from the true function.

Using a curve fitting technique like Gaussian reduction an N−1th degree polynomial interpolation of the function is found.