Diffraction

Diffraction is the deviation of waves from straight-line propagation without any change in their energy due to an obstacle or through an aperture.

[1]: 433 Italian scientist Francesco Maria Grimaldi coined the word diffraction and was the first to record accurate observations of the phenomenon in 1660.

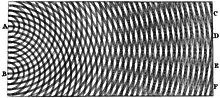

In classical physics, the diffraction phenomenon is described by the Huygens–Fresnel principle that treats each point in a propagating wavefront as a collection of individual spherical wavelets.

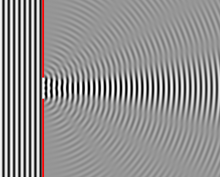

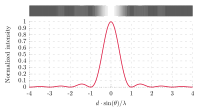

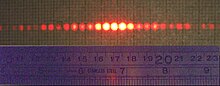

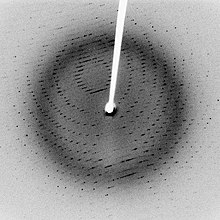

[2] The characteristic pattern is most pronounced when a wave from a coherent source (such as a laser) encounters a slit/aperture that is comparable in size to its wavelength, as shown in the inserted image.

Furthermore, quantum mechanics also demonstrates that matter possesses wave-like properties and, therefore, undergoes diffraction (which is measurable at subatomic to molecular levels).

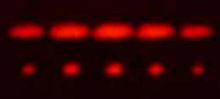

[10] Thomas Young performed a celebrated experiment in 1803 demonstrating interference from two closely spaced slits.

However, Augustin-Jean Fresnel took the prize with his new theory wave propagation,[12] combining the ideas[13] of Christiaan Huygens with Young's interference concept.

The wavefunction is determined by the physical surroundings such as slit geometry, screen distance, and initial conditions when the photon is created.

For matter waves a similar but slightly different approach is used based upon a relativistically corrected form of the Schrödinger equation,[17] as first detailed by Hans Bethe.

[18] The Fraunhofer and Fresnel limits exist for these as well, although they correspond more to approximations for the matter wave Green's function (propagator)[19] for the Schrödinger equation.

In the case of light shining through small circular holes, we will have to take into account the full three-dimensional nature of the problem.

This principle can be extended to engineer a grating with a structure such that it will produce any diffraction pattern desired; the hologram on a credit card is an example.

The speckle pattern which is observed when laser light falls on an optically rough surface is also a diffraction phenomenon.

[26] Diffraction can also be a concern in some technical applications; it sets a fundamental limit to the resolution of a camera, telescope, or microscope.

of the light onto the slit is non-zero (which causes a change in the path length), the intensity profile in the Fraunhofer regime (i.e. far field) becomes:

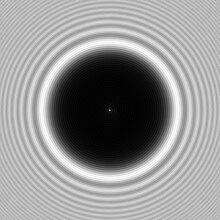

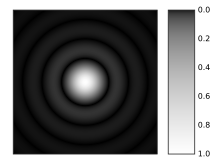

The far-field diffraction of a plane wave incident on a circular aperture is often referred to as the Airy disk.

The smaller the aperture, the larger the spot size at a given distance, and the greater the divergence of the diffracted beams.

By direct substitution, the solution to this equation can be readily shown to be the scalar Green's function, which in the spherical coordinate system (and using the physics time convention

The light is not focused to a point but forms an Airy disk having a central spot in the focal plane whose radius (as measured to the first null) is

The Rayleigh criterion specifies that two point sources are considered "resolved" if the separation of the two images is at least the radius of the Airy disk, i.e. if the first minimum of one coincides with the maximum of the other.

It is a result of the superposition of many waves with different phases, which are produced when a laser beam illuminates a rough surface.

Babinet's principle is a useful theorem stating that the diffraction pattern from an opaque body is identical to that from a hole of the same size and shape, but with differing intensities.

The knife-edge effect is explained by the Huygens–Fresnel principle, which states that a well-defined obstruction to an electromagnetic wave acts as a secondary source, and creates a new wavefront.

Knife-edge diffraction is an outgrowth of the "half-plane problem", originally solved by Arnold Sommerfeld using a plane wave spectrum formulation.

In 1974, Prabhakar Pathak and Robert Kouyoumjian extended the (singular) Keller coefficients via the uniform theory of diffraction (UTD).

Diffraction of matter waves has been observed for small particles, like electrons, neutrons, atoms, and even large molecules.

The short wavelength of these matter waves makes them ideally suited to study the atomic structure of solids, molecules and proteins.

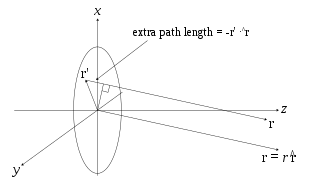

[30] The description of diffraction relies on the interference of waves emanating from the same source taking different paths to the same point on a screen.

Due to these short pulses, radiation damage can be outrun, and diffraction patterns of single biological macromolecules will be able to be obtained.

[34][35] Original : Nobis alius quartus modus illuxit, quem nunc proponimus, vocamusque; diffractionem, quia advertimus lumen aliquando diffringi, hoc est partes eius multiplici dissectione separatas per idem tamen medium in diversa ulterius procedere, eo modo, quem mox declarabimus.Translation : It has illuminated for us another, fourth way, which we now make known and call "diffraction" [i.e., shattering], because we sometimes observe light break up; that is, that parts of the compound [i.e., the beam of light], separated by division, advance farther through the medium but in different [directions], as we will soon show.