Burning of Cork

Firefighters testified that British forces hindered their attempts to tackle the blazes by intimidation, cutting their hoses and shooting at them.

More than 40 business premises, 300 residential properties, the City Hall and Carnegie Library were destroyed by fires, many of which were started by incendiary bombs.

The Auxiliaries and the "Black and Tans" became infamous for carrying out numerous reprisals for IRA attacks, which included extrajudicial killings and burning property.

[4] In March 1920, the republican Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomás Mac Curtain, was shot dead at his home by police with blackened faces.

[5] In reprisal for an IRA attack in Balbriggan on 20 September 1920, "Black and Tans" burnt more than fifty homes and businesses in the village and killed two local republicans in their custody.

[7][8] IRA intelligence officer Florence O'Donoghue said the subsequent burning and looting of Cork was "not an isolated incident, but rather the large-scale application of a policy initiated and approved, implicitly or explicitly, by the British government".

On 10 December, the British authorities declared martial law in counties Cork (including the city), Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary.

IRA volunteer Seán Healy recalled that "at least 1,000 troops would pour out of Victoria Barracks at this hour and take over complete control of the city".

Five of the volunteers hid behind a stone wall while one, Michael Kenny, stood across the road dressed as an off-duty British officer.

The Auxiliaries dragged one of them to the middle of the crossroads, stripped him naked and forced him to sing "God Save the King" until he collapsed on the road.

[13] Angered by an attack so near their headquarters and seeking retribution for the deaths of their colleagues at Kilmichael, the Auxiliaries gathered to wreak their revenge.

[19] At 9:30 pm, lorries of Auxiliaries and British soldiers left the barracks and alighted at Dillon's Cross, where they broke into houses and herded the occupants on to the street.

[21] British forces began driving around the city firing at random,[17] as people rushed to get home before the 10 pm curfew.

[27] Hutson oversaw the operation on St Patrick's Street, and met Cork Examiner reporter Alan Ellis.

He told Ellis "that all the fires were being deliberately started by incendiary bombs, and in several cases he had seen soldiers pouring cans of petrol into buildings and setting them alight".

[28] Firemen later testified that British forces hindered their attempts to tackle the blazes by intimidating them and cutting or driving over their hoses.

The last act of arson took place at about 6 am when a group of policemen looted and burnt the Murphy Brothers' clothes shop on Washington Street.

[34] It is thought that, while searching the ambush site, Auxiliaries had found a cap belonging to one of the volunteers and had used bloodhounds to follow the scent to the family's home.

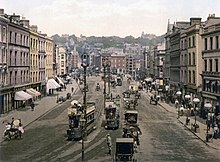

The streets ran with sooty water, the footpaths were strewn with broken glass and debris, ruins smoked and smouldered and over everything was the all-pervasive smell of burning.

Walsh said that while the people of Cork had been suffering, "not a single word of protest was uttered [by the bishop], and today, after the city has been decimated, he saw no better course than to add insult to injury".

Councillor Michael Ó Cuill, alderman Tadhg Barry and the Lord Mayor, Donal O'Callaghan, agreed with Walsh's sentiments.

[44] Three days after the burning, on 15 December, two lorry-loads of Auxiliaries were travelling from Dunmanway to Cork for the funeral of Spencer Chapman, their comrade killed at Dillon's Cross.

[48] In the British House of Commons, Sir Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, refused demands for such an inquiry.

[31][49] When asked about reports of firefighters being attacked by British forces he said "Every available policeman and soldier in Cork was turned out at once and without their assistance the fire brigade could not have gone through the crowds and did the work that they tried to do".

[49] Conservative Party leader Bonar Law said "in the present condition of Ireland, we are much more likely to get an impartial inquiry in a military court than in any other".

[50] The Irish Labour Party and Trades Union Congress published a pamphlet in January 1921 entitled Who burned Cork City?

Florence O'Donoghue, who was intelligence officer of the 1st Cork Brigade IRA at the time, wrote: What appears more probable is that the ambush provided the excuse for an act which was long premeditated and for which all arrangements had been made.

The rapidity with which supplies of petrol and Verey lights were brought from Cork barracks to the centre of the city, and the deliberate manner in which the work of firing the various premises was divided amongst groups under the control of officers, gives evidence of organisation and pre-arrangement.