Roman Britain

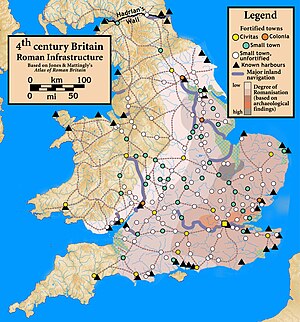

[9] In the early fourth century, Britannia was divided into four provinces under the direction of a vicarius, who administered the Diocese of the Britains, and who was himself under the overall authority of the praetorian prefecture of the Gallic region, based at Trier.

Despite the military failure, it was a political success, with the Roman Senate declaring a 20-day public holiday in Rome to honour the unprecedented achievement of obtaining hostages from Britain and defeating Belgic tribes on returning to the continent.

[15] The second invasion involved a substantially larger force and Caesar coerced or invited many of the native Celtic tribes to pay tribute and give hostages in return for peace.

[22] This policy was followed until 39 or 40 AD, when Caligula received an exiled member of the Catuvellaunian dynasty and planned an invasion of Britain that collapsed in farcical circumstances before it left Gaul.

The IX Hispana may have been permanently stationed, with records showing it at Eboracum (York) in 71 and on a building inscription there dated 108, before being destroyed in the east of the Empire, possibly during the Bar Kokhba revolt.

British archaeologist Richard Hingley said that the Roman conquest of Britain, beginning with Julius Caesar's expeditions and culminating with the construction of Hadrian's Wall, was a drawn-out process rather than an inevitable or swift victory.

Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, the conqueror of Mauretania (modern day Algeria and Morocco), then became governor of Britain, and in 60 and 61 he moved against Mona (Anglesey) to settle accounts with Druidism once and for all.

Around 105 there appears to have been a serious setback at the hands of the tribes of the Picts: several Roman forts were destroyed by fire, with human remains and damaged armour at Trimontium (at modern Newstead, in SE Scotland) indicating hostilities at least at that site.

Trajan's Dacian Wars may have led to troop reductions in the area or even total withdrawal followed by slighting of the forts by the Picts rather than an unrecorded military defeat.

In the reign of Antoninus Pius (138–161) the Hadrianic border was briefly extended north to the Forth–Clyde isthmus, where the Antonine Wall was built around 142 following the military reoccupation of the Scottish lowlands by a new governor, Quintus Lollius Urbicus.

The second occupation was probably connected with Antoninus's undertakings to protect the Votadini or his pride in enlarging the empire, since the retreat to the Hadrianic frontier occurred not long after his death when a more objective strategic assessment of the benefits of the Antonine Wall could be made.

Archaeological evidence shows that Senecio had been rebuilding the defences of Hadrian's Wall and the forts beyond it, and Severus's arrival in Britain prompted the enemy tribes to sue for peace immediately.

Carausius was a Menapian naval commander of the Britannic fleet; he revolted upon learning of a death sentence ordered by the emperor Maximian on charges of having abetted Frankish and Saxon pirates and having embezzled recovered treasure.

[44] The tasks of the vicarius were to control and coordinate the activities of governors; monitor but not interfere with the daily functioning of the Treasury and Crown Estates, which had their own administrative infrastructure; and act as the regional quartermaster-general of the armed forces.

In short, as the sole civilian official with superior authority, he had general oversight of the administration, as well as direct control, while not absolute, over governors who were part of the prefecture; the other two fiscal departments were not.

Little is known of his campaigns with scant archaeological evidence, but fragmentary historical sources suggest he reached the far north of Britain and won a major battle in early summer before returning south.

A series of forts had been built, starting around 280, to defend the coasts, but these preparations were not enough when, in 367, a general assault of Saxons, Picts, Scoti and Attacotti, combined with apparent dissension in the garrison on Hadrian's Wall, left Roman Britain prostrate.

Urban life had generally grown less intense by the fourth quarter of the 4th century, and coins minted between 378 and 388 are very rare, indicating a likely combination of economic decline, diminishing numbers of troops, problems with the payment of soldiers and officials or with unstable conditions during the usurpation of Magnus Maximus 383–87.

Mass-produced wheel thrown pottery ended at approximately the same time; the rich continued to use metal and glass vessels, while the poor made do with humble "grey ware" or resorted to leather or wooden containers.

[64] With the imperial layers of the military and civil government gone, administration and justice fell to municipal authorities, and local warlords gradually emerged all over Britain, still utilizing Romano-British ideals and conventions.

A significant date in sub-Roman Britain is the Groans of the Britons, an unanswered appeal to Aetius, leading general of the western Empire, for assistance against Saxon invasion in 446.

[66] During the Roman period Britain's continental trade was principally directed across the Southern North Sea and Eastern Channel, focusing on the narrow Strait of Dover, with more limited links via the Atlantic seaways.

[67][73][76] This came about as a result of the rapid decline in the size of the British garrison from the mid-3rd century onwards (thus freeing up more goods for export), and because of 'Germanic' incursions across the Rhine, which appear to have reduced rural settlement and agricultural output in northern Gaul.

At Wroxeter in Shropshire, stock smashed into a gutter during a 2nd-century fire reveals that Gaulish samian ware was being sold alongside mixing bowls from the Mancetter-Hartshill industry of the West Midlands.

In Britain, a governor's role was primarily military, but numerous other tasks were also his responsibility, such as maintaining diplomatic relations with local client kings, building roads, ensuring the public courier system functioned, supervising the civitates and acting as a judge in important legal cases.

To assist him in legal matters he had an adviser, the legatus juridicus, and those in Britain appear to have been distinguished lawyers perhaps because of the challenge of incorporating tribes into the imperial system and devising a workable method of taxing them.

[81] The various civitates sent representatives to a yearly provincial council in order to profess loyalty to the Roman state, to send direct petitions to the Emperor in times of extraordinary need, and to worship the imperial cult.

[99] The earliest confirmed written evidence for Christianity in Britain is a statement by Tertullian, c. 200 AD, in which he described "all the limits of the Spains, and the diverse nations of the Gauls, and the haunts of the Britons, inaccessible to the Romans, but subjugated to Christ".

A possible Roman 4th-century church and associated burial ground was also discovered at Butt Road on the south-west outskirts of Colchester during the construction of the new police station there, overlying an earlier pagan cemetery.

A letter found on a lead tablet in Bath, Somerset, datable to c. 363, had been widely publicised as documentary evidence regarding the state of Christianity in Britain during Roman times.