Diophantine equation

The solutions are described by the following theorem: Proof: If d is this greatest common divisor, Bézout's identity asserts the existence of integers e and f such that ae + bf = d. If c is a multiple of d, then c = dh for some integer h, and (eh, fh) is a solution.

On the other hand, for every pair of integers x and y, the greatest common divisor d of a and b divides ax + by.

The Chinese remainder theorem describes an important class of linear Diophantine systems of equations: let

The Chinese remainder theorem asserts that the following linear Diophantine system has exactly one solution

More generally, every system of linear Diophantine equations may be solved by computing the Smith normal form of its matrix, in a way that is similar to the use of the reduced row echelon form to solve a system of linear equations over a field.

Using matrix notation every system of linear Diophantine equations may be written

Hermite normal form may also be used for solving systems of linear Diophantine equations.

Nevertheless, Richard Zippel wrote that the Smith normal form "is somewhat more than is actually needed to solve linear diophantine equations.

Solving a homogeneous Diophantine equation is generally a very difficult problem, even in the simplest non-trivial case of three indeterminates (in the case of two indeterminates the problem is equivalent with testing if a rational number is the dth power of another rational number).

A witness of the difficulty of the problem is Fermat's Last Theorem (for d > 2, there is no integer solution of the above equation), which needed more than three centuries of mathematicians' efforts before being solved.

is completely reduced to finding the rational points of the corresponding projective hypersurface.

In this case, the problem may thus be solved by applying the method to an equation with fewer variables.

In the general case, consider the parametric equation of a line passing through R: Substituting this in q, one gets a polynomial of degree two in x1, that is zero for x1 = r1.

These quadratic polynomials with integer coefficients form a parameterization of the projective hypersurface defined by Q: A point of the projective hypersurface defined by Q is rational if and only if it may be obtained from rational values of

are homogeneous polynomials, the point is not changed if all ti are multiplied by the same rational number.

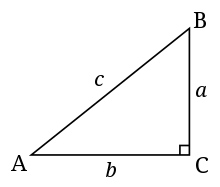

In this section, we show how the above method allows retrieving Euclid's formula for generating Pythagorean triples.

For retrieving exactly Euclid's formula, we start from the solution (−1, 0, 1), corresponding to the point (−1, 0) of the unit circle.

A line passing through this point may be parameterized by its slope: Putting this in the circle equation one gets Dividing by x + 1, results in which is easy to solve in x: It follows Homogenizing as described above one gets all solutions as where k is any integer, s and t are coprime integers, and d is the greatest common divisor of the three numerators.

This description of the solutions differs slightly from Euclid's formula because Euclid's formula considers only the solutions such that x, y, and z are all positive, and does not distinguish between two triples that differ by the exchange of x and y, The questions asked in Diophantine analysis include: These traditional problems often lay unsolved for centuries, and mathematicians gradually came to understand their depth (in some cases), rather than treat them as puzzles.

Many well known puzzles in the field of recreational mathematics lead to diophantine equations.

Stated in more modern language, "The equation an + bn = cn has no solutions for any n higher than 2."

Following this, he wrote: "I have discovered a truly marvelous proof of this proposition, which this margin is too narrow to contain."

Such a proof eluded mathematicians for centuries, however, and as such his statement became famous as Fermat's Last Theorem.

In 1900, David Hilbert proposed the solvability of all Diophantine equations as the tenth of his fundamental problems.

In 1970, Yuri Matiyasevich solved it negatively, building on work of Julia Robinson, Martin Davis, and Hilary Putnam to prove that a general algorithm for solving all Diophantine equations cannot exist.

The central idea of Diophantine geometry is that of a rational point, namely a solution to a polynomial equation or a system of polynomial equations, which is a vector in a prescribed field K, when K is not algebraically closed.

Another general method is the Hasse principle that uses modular arithmetic modulo all prime numbers for finding the solutions.

The difficulty of solving Diophantine equations is illustrated by Hilbert's tenth problem, which was set in 1900 by David Hilbert; it was to find an algorithm to determine whether a given polynomial Diophantine equation with integer coefficients has an integer solution.

Examples include: A general theory for such equations is not available; particular cases such as Catalan's conjecture and Fermat's Last Theorem have been tackled.

However, the majority are solved via ad-hoc methods such as Størmer's theorem or even trial and error.