Insect wing

The wings are strengthened by a number of longitudinal veins, which often have cross-connections that form closed "cells" in the membrane (extreme examples include the dragonflies and lacewings).

The patterns resulting from the fusion and cross-connection of the wing veins are often diagnostic for different evolutionary lineages and can be used for identification to the family or even genus level in many orders of insects.

Two types of hair may occur on the wings: microtrichia, which are small and irregularly scattered, and macrotrichia, which are larger, socketed, and may be restricted to veins.

Large numbers of cross-veins are present in some insects, and they may form a reticulum as in the wings of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) and at the base of the forewings of Tettigonioidea and Acridoidea (katydids and grasshoppers respectively).

Since all winged insects are believed to have evolved from a common ancestor, the archedictyon represents the "template" that has been modified (and streamlined) by natural selection for 200 million years.

The stem of the media is often united with the radius, but when it occurs as a distinct vein its base is associated with the distal median plate (m') or is continuously sclerotized with the latter.

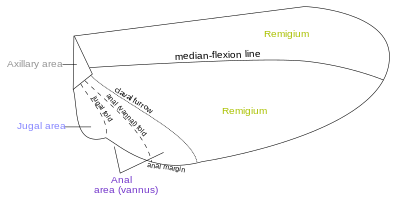

[14] There are about four different fields found on the insect wings: Most veins and crossveins occur in the anterior area of the remigium, which is responsible for most of the flight, powered by the thoracic muscles.

When the jugal area of the forewing is developed as a free lobe, it projects beneath the humeral angle of the hindwing and thus serves to yoke the two wings together.

In many Diptera a deep incision of the anal area of the wing membrane behind the single vannal vein sets off a proximal alar lobe distal to the outer squama of the alula.

The third axillary, therefore, is usually the posterior hinge plate of the wing base and is the active sclerite of the flexor mechanism, which directly manipulates the vannal veins.

The contraction of the flexor muscle (D) revolves the third axillary on its mesal articulations (b, f) and thereby lifts its distal arm; this movement produces the flexion of the wing.

The distal plate (m') is less constantly present as a distinct sclerite and may be represented by a general sclerotization of the base of the mediocubital field of the wing.

In more derived orders of insects, such as Diptera (flies) and Hymenoptera (wasp), the indirect muscles occupy the greatest volume of the pterothorax and function as the primary source of power for the wingstroke.

The most primitive extant flying insects, Ephemeroptera (mayflies) and Odonata (dragonflies), use direct muscles that are responsible for developing the needed power for the up and down strokes.

The fuel and oxygen rich blood is carried to the muscles through diffusion occurring in large amounts, in order to maintain the high level of energy used during flight.

The earliest winged insects are from this time period (Pterygota), including the Blattoptera, Caloneurodea, primitive stem-group Ephemeropterans, Orthoptera and Palaeodictyopteroidea.

[39] Their prototypes may have had the beginnings of many modern attributes even by late Carboniferous and it is possible that they even captured small vertebrates, for some species had a wing span of 71 cm.

Hemiptera, or true bugs had appeared in the form of Arctiniscytina and Paraknightia having forewings with unusual venation, possibly diverging from Blattoptera.

Crosby).This family Tilliardipteridae, despite the numerous 'tipuloid' features, should be included in Psychodomorpha sensu Hennig on account of loss of the convex distal 1A reaching wing margin and formation of the anal loop.

[45] An alternative idea is that it derives from directed aerial gliding descent—a preflight phenomena found in some apterygote, a wingless sister taxa to the winged insects.

[32] Natural selection has played an enormous role in refining the wings, control and sensory systems, and anything else that affects aerodynamics or kinematics.

[47] The first indication of the wing buds is of a thickening of the hypodermis, which can be observed in insect species as early the embryo, and in the earliest stages of the life cycle.

It is not until the butterfly is in its pupal stage that the wing-bud becomes exposed, and shortly after eclosion, the wing begins to expand and form its definitive shape.

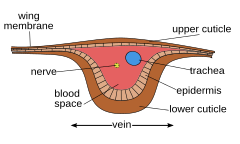

[47] In the earlier stages of its development, the wing-bud is not provided with special organs of respiration such as tracheation, as it resembles in this respect the other portions of the hypodermis of which it is still a part.

The histoblast is developed near a large trachea, a cross-section of which is shown in, which represents sections of these parts of the first, second, third and fourth instars respectively.

In many species of Sphingidae (sphinx moths), the forewings are large and sharply pointed, forming with the small hindwings a triangle that is suggestive of the wings of fast, modern airplanes.

The mesothorax is evolved to have more powerful muscles to propel moth or butterfly through the air, with the wing of said segment having a stronger vein structure.

Until the early years of the 20th century Odonata were often regarded as being related to lacewings and were given the ordinal name Paraneuroptera, but any resemblance between these two orders is entirely superficial.

[49] Other orders such as the Dermaptera (earwigs), Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets), Mantodea (praying mantis) and Blattodea (cockroaches) have rigid leathery forewings that are not flapped while flying, sometimes called tegmen (pl.

[13] Termites are relatively poor fliers and are readily blown downwind in wind speeds of less than 2 km/h, shedding their wings soon after landing at an acceptable site, where they mate and attempt to form a nest in damp timber or earth.

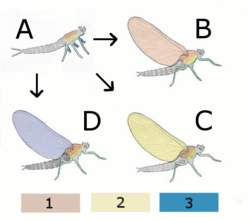

A Hypothetical wingless ancestor

B Paranotal theory:

Hypothetical insect with wings from the back (Notum)

C Hypothetical insect with wings from the Pleurum

D Epicoxal theory

Hypothetical insect with wings from annex of the legs

1 Notum (back)

2 Pleurum

3 Exite (outer attachments of the legs)