Discovery Expedition

Further achievements included the discoveries of the Cape Crozier emperor penguin colony, King Edward VII Land, and the Polar Plateau (via the western mountains route) on which the South Pole is located.

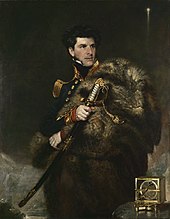

Markham's vision of a full-blown naval affair after the style of Ross or Franklin was opposed by sections of the joint committee, but his tenacity was such that the expedition was eventually moulded largely to his wishes.

Thirteen years later, Scott, by now a torpedo lieutenant on HMS Majestic, was looking for a path to career advancement, and a chance meeting with Sir Clements in London led him to apply for the leadership of the expedition.

[15] However, the Joint Committee had, with Markham's acquiescence, secured the appointment of John Walter Gregory, Professor of Geology at the University of Melbourne and former assistant geologist at the British Museum, as the expedition's scientific director.

[19][B] Among the lower deck complement were some who became Antarctic veterans, including Frank Wild, William Lashly, Thomas Crean (who joined the expedition following the desertion of a seaman in New Zealand),[21] Edgar Evans and Ernest Joyce.

Marine biologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, from Plymouth Museum, was a more mature figure, as was the senior of the two doctors, Reginald Koettlitz, who, at 39, was the oldest member of the expedition.

[25] The junior doctor and zoologist was Edward Wilson, who became close to Scott and provided the qualities of calmness, patience and detachment that the captain reportedly lacked.

She eventually sailed under the Merchant Shipping Act, flying the RGS house flag and the Blue Ensign and burgee of the Royal Harwich Yacht Club.

At McMurdo Sound Discovery turned eastward, touching land again at Cape Crozier where a pre-arranged message point was set up so that relief ships would be able to locate the expedition.

Wilson wrote: "We all realized our extreme good fortune in being led to such a winter quarter as this, safe for the ship, with perfect shelter from all ice pressure.

Scott had decided that the expedition should continue to live and work aboard ship, and he allowed Discovery to be frozen into the sea ice, leaving the main hut to be used as a storeroom and shelter.

[54] The dangers of the unfamiliar conditions were confirmed when, on 11 March, a party returning from an attempted journey to Cape Crozier became stranded on an icy slope during a blizzard.

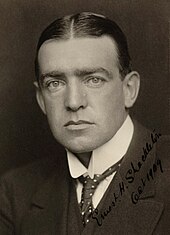

[57] As winter ended, trial sledge runs resumed, to test equipment and rations in advance of the planned southern journey which Scott, Wilson and Shackleton were to undertake.

The expedition's organisers had assumed that the Discovery would be free from the ice in early 1903, enabling Scott to carry out further seaborne exploration and survey work before winter set in.

Armitage's reconnaissance party of the previous year had pioneered a route up to altitude 8,900 feet (2,700 m) before returning, but Scott wished to march west from this point, if possible to the location of the South Magnetic Pole.

After the return of geological and supporting parties, Scott, Evans and Lashly continued westward across the featureless plain for another eight days, covering a distance of about 150 miles to reach their most westerly point on 30 November.

The return journey to the Ferrar Glacier was undertaken in conditions which limited them to no more than a mile an hour, with supplies running low and dependent on Scott's rule of thumb navigation.

[73] On the descent of the glacier Scott and Evans survived a potentially fatal fall into a crevasse, before the discovery of a snow-free area or dry valley, a rare Antarctic phenomenon.

Another party had explored the Koettlitz Glacier to the south-west, and Wilson had travelled to Cape Crozier to observe the emperor penguin colony at close quarters.

Work had begun with ice saws, but after 12 days' labour only two short parallel cuts of 450 feet (140 m) had been carved, with the ship still 20 miles (32 km) from open water.

Explosives were used to break up the ice, and the sawing parties resumed work, but although the relief ships were able to edge closer, by the end of January Discovery remained icebound, two miles (approx.

[79] A final explosive charge removed the remaining ice on 16 February, and the following day, after a last scare when she became temporarily grounded on a shoal, Discovery began the return journey to New Zealand.

Scott was quickly promoted to captain, and invited to Balmoral Castle to meet King Edward VII, who invested him as a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO).

On the medical side, Wilson discovered the anti-scorbutic effects of fresh seal meat, which resolved the lethal threat of scurvy to this and subsequent expeditions.

[92] However, when the meteorological data were published their accuracy was disputed within the scientific establishment, including by the President of the Physical Society of London, Dr Charles Chree.

In particular, the glorification by Scott of man-hauling as something intrinsically more noble than other ice travel techniques led to a general distrust of methods involving ski and dogs, a mindset that was carried forward into later expeditions.

Apart from Scott and Shackleton, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce from the lower deck returned repeatedly to the ice, apparently unable to settle back into normal life.

[106] William Lashly and Edgar Evans, Scott's companions on the 1903 western journey, aligned themselves with their leader's future plans and became his regular sledging partners.

[107] Soon after resuming his naval duties, Scott revealed to the Royal Geographical Society his intention to return to Antarctica, but the information was not at that stage made public.

[108] Scott was forestalled by Shackleton, who early in 1907 announced his plans to lead an expedition with the twin objectives of reaching the geographic and magnetic South Poles.