Discovery of nuclear fission

[8] Subsequently, Paul Villard discovered a third type of Becquerel radiation which, following Rutherford's scheme, were called "gamma rays", and Curie noted that radium also produced a radioactive gas.

[15][16][17] Soddy and Kasimir Fajans independently observed in 1913 that alpha decay caused atoms to shift down two places in the periodic table, while the loss of two beta particles restored it to its original position.

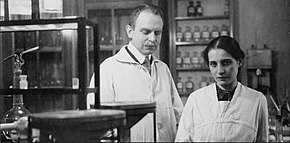

At McGill he had become accustomed to working closely with a physicist, so he teamed up with Lise Meitner, who had received her doctorate from the University of Vienna in 1906, and had then moved to Berlin to study physics under Max Planck at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität.

Meitner submitted her and Hahn's findings for publication in March 1918 to the scientific paper Physikalischen Zeitschrift under the title Die Muttersubstanz des Actiniums; ein neues radioaktives Element von langer Lebensdauer.

[33] Just a few weeks before Cockcroft and Walton's feat, another scientist at the Cavendish Laboratory, James Chadwick, discovered the neutron, using an ingenious device made with sealing wax, through the reaction of beryllium with alpha particles:[34][35] Irène Curie and Frédéric Joliot irradiated aluminium foil with alpha particles and found that this results in a short-lived radioactive isotope of phosphorus with a half-life of around three minutes: which then decays to a stable isotope of silicon: They noted that radioactivity continued after the neutron emissions ceased.

But Rasetti went on his Easter vacation without preparing the polonium-beryllium source, and Fermi realised that since he was interested in the products of the reaction, he could irradiate his sample in one laboratory and test it in another down the hall.

[40][41] Working in assembly-line fashion, they started by irradiating water, and then progressed up the periodic table through lithium, beryllium, boron and carbon, without inducing any radioactivity.

[42][43] Meitner was one of the select group of physicists to whom Fermi mailed advance copies of his papers, and she was able to report that she had verified his findings with respect to aluminium, silicon, phosphorus, copper and zinc.

[41] When a new copy of La Ricerca Scientifica arrived at the Niels Bohr's Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, her nephew, Otto Frisch, as the only physicist there who could read Italian, found himself in demand from colleagues wanting a translation.

Following the displacement law, they checked for the presence of lead, bismuth, radium, actinium, thorium and protactinium (skipping the elements whose chemical properties were unknown), and (correctly) found no indication of any of them.

[47] However, in this paper Fermi cautioned that "a careful search for such heavy particles has not yet been carried out, as they require for their observation that the active product should be in the form of a very thin layer.

[45] Leo Szilard and Thomas A. Chalmers reported that neutrons generated by gamma rays acting on beryllium were captured by iodine, a reaction that Fermi had also noted.

When Meitner repeated their experiment, she found that neutrons from the gamma-beryllium sources were captured by heavy elements like iodine, silver and gold, but not by lighter ones like sodium, aluminium and silicon.

[53] His simple and elegant model was refined and developed by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and, after the discovery of the neutron, by Werner Heisenberg in 1935 and Niels Bohr in 1936.

In the model, the nucleons were held together in the smallest possible volume (a sphere) by the strong nuclear force, which was capable of overcoming the longer ranged Coulomb electrical repulsion between the protons.

The model remained in use for certain applications into the 21st century, when it attracted the attention of mathematicians interested in its properties,[54][55][56] but in its 1934 form it confirmed what physicists thought they already knew: that nuclei were static, and that the odds of a collision chipping off more than an alpha particle were practically zero.

Meitner never tried to conceal her Jewish descent, but initially was exempt from its impact on multiple grounds: she had been employed before 1914, had served in the military during the World War, was an Austrian rather than a German citizen, and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was a government-industry partnership.

[72] Carl Bosch, the director of IG Farben, a major sponsor of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, assured Meitner that her position there was safe, and she agreed to stay.

[79][80][81] Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion ("Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion.

They investigated the chemistry, and found that the 3.5-hour activity was coming from something that seemed to be chemically similar to lanthanum (which in fact it was), which they attempted unsuccessfully to isolate with a fractional crystallization process.

[99][100] Nonetheless, she had immediately written back to Hahn to say: "At the moment the assumption of such a thoroughgoing breakup seems very difficult to me, but in nuclear physics we have experienced so many surprises, that one cannot unconditionally say: 'It is impossible.

Logically, if barium was formed, the other element must be krypton,[105] although Hahn mistakenly believed that the atomic masses had to add up to 239 rather than the atomic numbers adding up to 92, and thought it was masurium (technetium), and so did not check for it:[106] Over a series of long-distance phone calls, Meitner and Frisch came up with a simple experiment to bolster their claim: to measure the recoil of the fission fragments, using a Geiger counter with the threshold set above that of the alpha particles.

[121] This would be experimentally verified in February 1940, after Alfred Nier was able to produce sufficient pure uranium-235 for John R. Dunning, Aristid von Grosse and Eugene T. Booth to test.

[127] Both Hahn and Meitner had been nominated for the chemistry and the physics Nobel Prizes many times even before the discovery of nuclear fission for their work on radioactive isotopes and protactinium.

[132]In 1946, the Nobel Committee for Physics considered nominations for Meitner and Frisch received from Max von Laue, Niels Bohr, Oskar Klein, Egil Hylleraas and James Franck.

As president of the Max Planck Society from 1946 to 1960, he projected an image of German science as undiminished in brilliance and untainted by Nazism to an audience that wanted to believe it.

Lawrence Badash wrote: "His wartime recognition of the perversion of science for the construction of weapons and his postwar activity in planning the direction of his country's scientific endeavours now inclined him increasingly toward being a spokesman for social responsibility.

She attended a cocktail party for Lieutenant General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project (who gave her sole credit for the discovery of fission in his 1962 memoirs), and was named Woman of the Year by the Women's National Press Club.

[146] Meitner's diploma bore the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies leading to the discovery of fission".

Scientists questioned the focus on chemistry, historians challenged the accepted narrative of the Nazi period, and feminists saw Meitner as yet another example of the Matilda effect, where a woman had been airbrushed from the pages of history.