Discovery of penicillin

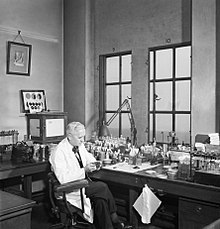

While working at St Mary's Hospital in London in 1928, Scottish physician Alexander Fleming was the first to experimentally demonstrate that a Penicillium mould secretes an antibacterial substance, which he named "penicillin".

In 1939, a team of scientists at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford, led by Howard Florey that included Edward Abraham, Ernst Chain, Norman Heatley and Margaret Jennings, began researching penicillin.

They carried out experiments with animals to determine penicillin's safety and effectiveness before conducting clinical trials and field tests.

The private sector and the United States Department of Agriculture located and produced new strains and developed mass production techniques.

Many ancient cultures, including those in Australia, China, Egypt, Greece and India, independently discovered the useful properties of fungi and plants in treating infection.

[1][2] While working at St Mary's Hospital, London, in 1928, a Scottish physician, Alexander Fleming, was investigating the pattern of variation in S. aureus.

Their experiment was successful and Fleming was planning and agreed to write a report in A System of Bacteriology to be published by the Medical Research Council (MRC) by the end of 1928.

[3] In August, Fleming spent the summer break with his family at his country home The Dhoon at Barton Mills, Suffolk.

While on vacation, he was appointed Professor of Bacteriology at the St Mary's Hospital Medical School on 1 September 1928.

He later recounted his experience: When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer.

He called this juice "penicillin", explaining the reason as "to avoid the repetition of the rather cumbersome phrase 'Mould broth filtrate'.

It was due to his failure to isolate the compound that Fleming practically abandoned further research on the chemical aspects of penicillin.

He was fortunate that Charles John Patrick La Touche, an Irish botanist, had just recently joined St Mary's as a mycologist to investigate fungi as the cause of asthma.

[20] Whole genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis in 2011 revealed that Fleming's mould belongs to P. rubens, a species described by Belgian microbiologist Philibert Biourge in 1923.

[24] Ronald Hare also agreed in 1970 that the window was most often locked because it was difficult to reach due to a large table with apparatuses placed in front of it.

[23] Fleming gave some of his original penicillin samples to his colleague, surgeon Arthur Dickson Wright for clinical testing in 1928.

[28] In 1930 and 1931, Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in Sheffield, was the first to successfully use penicillin for medical treatment.

[29] He attempted to treat sycosis (eruptions in beard follicles) with penicillin but was unsuccessful, probably because the drug did not penetrate deep enough into the skin.

E. Breen, a fellow member of the Chelsea Arts Club, once asked Fleming if he thought it would ever be possible to make practical use of penicillin.

[36] In 1944, Margaret Jennings determined how penicillin acts, and showed that it has no lytic effects on mature organisms, including staphylococci; lysis occurs only if penicillin acts on bacteria during their initial stages of division and growth, when it interferes with the metabolic process that forms the cell wall.

[37][38][14] In 1939, ten years after work ceased at St. Mary's, a team of scientists at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford, led by Howard Florey that included Edward Abraham, Ernst Chain, Norman Heatley and Margaret Jennings, began researching penicillin.

[41][42][43] They developed a method for cultivating the mould and extracting, purifying and storing penicillin from it,[44][45] together with an assay for measuring its purity.

[44][46] They carried out experiments with animals to determine penicillin's safety and effectiveness before conducting clinical trials and field tests.

[37][49][50] The private sector and the United States Department of Agriculture located and produced new strains and developed mass production techniques.

The British medical historian Bill Bynum wrote:The discovery and development of penicillin is an object lesson of modernity: the contrast between an alert individual (Fleming) making an isolated observation and the exploitation of the observation through teamwork and the scientific division of labour (Florey and his group).

The secretary of the Nobel committee, Göran Liljestrand, made an assessment of Fleming and Florey in the same year, but little was known about penicillin in Sweden at the time, and he concluded that more information was required.

[58][59][60] The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute considered awarding half to Fleming and one-quarter each to Florey and Chain, but in the end decided to divide it equally three ways.

[58] On 25 October 1945, it announced that Fleming, Florey and Chain equally shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases.