Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming FRS FRSE FRCS[2] (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin.

His discovery in 1928 of what was later named benzylpenicillin (or penicillin G) from the mould Penicillium rubens has been described as the "single greatest victory ever achieved over disease".

The captain of the club, wishing to retain Fleming in the team, suggested that he join the research department at St Mary's, where he became assistant bacteriologist to Sir Almroth Wright, a pioneer in vaccine therapy and immunology.

Commissioned lieutenant in 1914 and promoted captain in 1917,[11] Fleming served throughout World War I in the Royal Army Medical Corps, and was Mentioned in Dispatches.

Serving as a temporary lieutenant of the Royal Army Medical Corps, he witnessed the death of many soldiers from sepsis resulting from infected wounds.

[12] In an article published in the medical journal The Lancet in 1917, he described an ingenious experiment, which he was able to conduct as a result of his own glassblowing skills, in which he explained why antiseptics were killing more soldiers than infection itself during the war.

[13] Wright strongly supported Fleming's findings, but despite this, most army physicians over the course of the war continued to use antiseptics even in cases where this worsened the condition of the patients.

His further tests with sputum, cartilage, blood, semen, ovarian cyst fluid, pus, and egg white showed that the bactericidal agent was present in all of these.

[17] Although he was able to obtain larger amounts of lysozyme from egg whites, the enzyme was only effective against small counts of harmless bacteria, and therefore had little therapeutic potential.

"[16] He also identified the bacterium present in the nasal mucus as Micrococcus Lysodeikticus, giving the species name (meaning "lysis indicator" for its susceptibility to lysozymal activity).

"[23] It was only towards the end of the 20th century that the true importance of Fleming's discovery in immunology was realised as lysozyme became the first antimicrobial protein discovered that constitute part of our innate immunity.

When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn't plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world's first antibiotic, or bacteria killer.

In 1928, he studied the variation of Staphylococcus aureus grown under natural condition, after the work of Joseph Warwick Bigger, who discovered that the bacterium could grow into a variety of types (strains).

Henry Dale, the then Director of National Institute for Medical Research and chair of the meeting, much later reminisced that he did not even sense any striking point of importance in Fleming's speech.

[41][42] Shortly after the team published its first results in 1940, Fleming telephoned Howard Florey, Chain's head of department, to say that he would be visiting within the next few days.

[47] In his first clinical trial, Fleming treated his research scholar Stuart Craddock who had developed severe infection of the nasal antrum (sinusitis).

Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in Sheffield and former student of Fleming, was the first to use penicillin successfully for medical treatment.

However, the report that "Keith was probably the first patient to be treated clinically with penicillin ointment"[56] is no longer true as Paine's medical records showed up.

[65] As to the chemical isolation and purification, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford took up the research to mass-produce it, which they achieved with support from World War II military projects under the British and US governments.

[67] In August 1942, Harry Lambert (an associate of Fleming's brother Robert) was admitted to St Mary's Hospital due to a life-threatening infection of the nervous system (streptococcal meningitis).

The War Cabinet was convinced of the usefulness upon which Sir Cecil Weir, Director General of Equipment, called for a meeting on the mode of action on 28 September 1942.

The committee consisted of Weir as chairman, Fleming, Florey, Sir Percival Hartley, Allison and representatives from pharmaceutical companies as members.

The main goals were to produce penicillin rapidly in large quantities with collaboration of American companies, and to supply the drug exclusively for Allied armed forces.

In such cases the thoughtless person playing with penicillin is morally responsible for the death of the man who finally succumbs to infection with the penicillin-resistant organism.

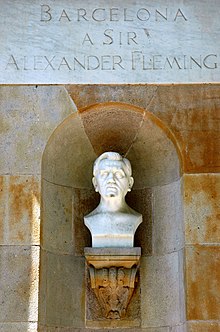

The Sir Alexander Fleming Building on the South Kensington campus was opened in 1998, where his son Robert and his great-granddaughter Claire were presented to the Queen; it is now one of the main preclinical teaching sites of the Imperial College School of Medicine.

His other alma mater, the Royal Polytechnic Institution (now the University of Westminster) has named one of its student halls of residence Alexander Fleming House, which is near to Old Street.

By the middle of the century, Fleming's discovery had spawned a huge pharmaceutical industry, churning out synthetic penicillins that would conquer some of mankind's most ancient scourges, including syphilis, gangrene and tuberculosis.

When Fleming used the first few samples prepared by the Oxford team to treat Harry Lambert who had streptococcal meningitis,[3] the successful treatment was major news, particularly popularised in The Times.

Wright wrote to the editor of The Times, which eagerly interviewed Fleming, but Florey prohibited the Oxford team from seeking media coverage.

He was saved by the new sulphonamide drug sulphapyridine, known at the time under the research code M&B 693, discovered and produced by May & Baker Ltd, Dagenham, Essex – a subsidiary of the French group Rhône-Poulenc.