Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot was born in Cairo, Egypt,[13] the oldest of the four daughters whose parents worked in North Africa and the middle East in the colonial administration and later as archaeologists.

[14] Her parents were John Winter Crowfoot (1873–1959), working for the country's Ministry of Education, and his wife Grace Mary (née Hood) (1877–1957), known to friends and family as Molly.

[15] The family lived in Cairo during the winter months, returning to England each year to avoid the hotter part of the season in Egypt.

[17][18] In 1921 Hodgkin's father entered her in the Sir John Leman Grammar School in Beccles, England,[10] where she was one of two girls allowed to study chemistry.

[19] Only once, when she was 13, did she make an extended visit to her parents, then living in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, where her father was Principal of Gordon College.

[20] Resuming the pre-war pattern, her parents lived and worked abroad for part of the year, returning to England and their children for several months every summer.

In 1926, on his retirement from the Sudan Civil Service, her father took the post of Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, where he and her mother remained until 1935.

[21] In 1928, Hodgkin joined her parents at the archaeological site of Jerash, in present-day Jordan, where she documented the patterns of mosaics from multiple Byzantine-era Churches dated to the 5th–6th centuries.

She spent more than a year finishing the drawings as she started her studies in Oxford, while also conducting chemical analyses of glass tesserae from the same site.

[22] Her attention to detail through the creation of precise scale drawings of these mosaics mirrors her subsequent work in recognising and documenting patterns in chemistry.

[14] Hodgkin developed a passion for chemistry from a young age, and her mother, a proficient botanist, fostered her interest in the sciences.

On her 16th birthday her mother gave her a book by W. H. Bragg on X-ray crystallography, "Concerning the Nature of Things", which helped her decide her future.

Her Leman School headmaster, George Watson, gave her personal tuition in the subject, enabling her to pass the University of Oxford entrance examination.

[29] The pepsin experiment is largely credited to Hodgkin, however she always made it clear that it was Bernal who initially took the photographs and gave her additional key insights.

[32] In April 1953, together with Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton, Hodgkin was one of the first people to travel from Oxford to Cambridge to see the model of the double helix structure of DNA, constructed by Francis Crick and James Watson, which was based on data and technique acquired by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin.

According to the late Dr Beryl Oughton (married name, Rimmer), they drove to Cambridge in two cars after Hodgkin announced that they were off to see the model of the structure of DNA.

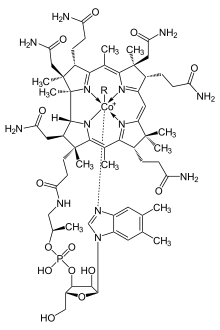

[36] In 1945, Hodgkin and her colleagues, including biochemist Barbara Low, solved the structure of penicillin, demonstrating, contrary to scientific opinion at the time, that it contains a β-lactam ring.

[47] After some treatment, Hodgkin returned to the lab, where she struggled to use the main switch on the x-ray equipment due to the condition of her hands.

[49] In 1937, Dorothy Crowfoot married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, an historian's son, who was then teaching an adult-education class in mining and industrial communities in the north of England after he resigned from the Colonial Office.

[50] He was an intermittent member of the Communist Party and later wrote several major works on African politics and history, becoming a well-known lecturer at Balliol College in Oxford.

Overall, Thomas Hodgkin spent extended periods of time in West Africa, where he was an enthusiastic supporter and chronicler of the emerging postcolonial states.

Hodgkin published as "Dorothy Crowfoot" until 1949, when she was persuaded by Hans Clarke's secretary to use her married name on a chapter she contributed to The Chemistry of Penicillin.

[59] Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Hodgkin established and maintained lasting contacts with scientists in her field abroad—at the Institute of Crystallography in Moscow; in India; and with the Chinese group working in Beijing and Shanghai on the structure of insulin.

[60] Particularly memorable was the visit in 1971 after the Chinese group themselves independently solved the structure of insulin, later than Hodgkin's team but to a higher resolution.

At the age of 73, Hodgkin wrote a foreword to the English edition of Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene, published by Robert Maxwell as the work of Elena Ceaușescu, wife of Romania's communist dictator.

[62] Because of Hodgkin's political activities, and her husband's association with the Communist Party, she was banned from entering the US in 1953 and subsequently not allowed to visit the country except by CIA waiver.

[57][67][68] A portrait of Dorothy Hodgkin by Bryan Organ was commissioned by private subscription to become part of the collection of the Royal Society.