Floppy disk

Originally designed to be more practical than the 8-inch format, it was becoming considered too large; as the quality of recording media grew, data could be stored in a smaller area.

The advantages of the 3½-inch disk were its higher capacity, its smaller physical size, and its rigid case which provided better protection from dirt and other environmental risks.

By the early 1990s, the increasing software size meant large packages like Windows or Adobe Photoshop required a dozen disks or more.

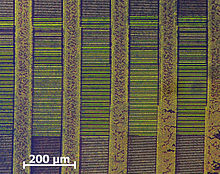

[15] An attempt to enhance the existing 3½-inch designs was the SuperDisk in the late 1990s, using very narrow data tracks and a high precision head guidance mechanism with a capacity of 120 MB[16] and backward-compatibility with standard 3½-inch floppies; a format war briefly occurred between SuperDisk and other high-density floppy-disk products, although ultimately recordable CDs/DVDs, solid-state flash storage, and eventually cloud-based online storage would render all these removable disk formats obsolete.

Other formats, such as magneto-optical discs, had the flexibility of floppy disks combined with greater capacity, but remained niche due to costs.

High-capacity backward compatible floppy technologies became popular for a while and were sold as an option or even included in standard PCs, but in the long run, their use was limited to professionals and enthusiasts.

Flash-based USB thumb drives finally provided a practical and popular replacement that supported traditional file systems and all common usage scenarios of floppy disks.

The music and theatre industries still use equipment requiring standard floppy disks (e.g. synthesizers, samplers, drum machines, sequencers, and lighting consoles).

This equipment may not be replaced due to cost or requirement for continuous availability; existing software emulation and virtualization do not solve this problem because a customized operating system is used that has no drivers for USB devices.

Hardware floppy disk emulators can be made to interface floppy-disk controllers to a USB port that can be used for flash drives.

In May 2016, the United States Government Accountability Office released a report that covered the need to upgrade or replace legacy computer systems within federal agencies.

According to this document, old IBM Series/1 minicomputers running on 8-inch floppy disks are still used to coordinate "the operational functions of the United States' nuclear forces".

The 8-inch and 5¼-inch floppy disks contain a magnetically coated round plastic medium with a large circular hole in the center for a drive's spindle.

The fabric is designed to reduce friction between the medium and the outer cover, and catch particles of debris abraded off the disk to keep them from accumulating on the heads.

[citation needed] A small notch on the side of the disk identifies whether it is writable, as detected by a mechanical switch or photoelectric sensor.

The latter worked because single- and double-sided disks typically contained essentially identical actual magnetic media, for manufacturing efficiency.

This small signal is amplified and sent to the floppy disk controller, which converts the streams of pulses from the media into data, checks it for errors, and sends it to the host computer system.

During formatting, the magnetizations of the particles are aligned forming tracks, each broken up into sectors, enabling the controller to properly read and write data.

A cyclic redundancy check (CRC) is written into the sector headers and at the end of the user data so that the disk controller can detect potential errors.

This physical striking is responsible for the 5¼-inch drive clicking during the boot of an Apple II, and the loud rattles of its DOS and ProDOS when disk errors occurred and track zero synchronization was attempted.

[citation needed] The Apple II computer system is notable in that it did not have an index hole sensor and ignored the presence of hard or soft sectoring.

[citation needed] In IBM-compatible PCs, the three densities of 3½-inch floppy disks are backwards-compatible; higher-density drives can read, write and format lower-density media.

Data is generally written to floppy disks in sectors (angular blocks) and tracks (concentric rings at a constant radius).

For example, Microsoft applications were often distributed on 3½-inch 1.68 MB DMF disks formatted with 21 sectors instead of 18; they could still be recognized by a standard controller.

[79] This higher capacity came with a disadvantage: the format used a unique drive mechanism and control circuitry, meaning that Mac disks could not be read on other computers.

Areas of the disk unusable for storage due to flaws can be locked (marked as "bad sectors") so that the operating system does not attempt to use them.

[citation needed] Mixtures of decimal prefixes and binary sector sizes require care to properly calculate total capacity.

Whereas semiconductor memory naturally favors powers of two (size doubles each time an address pin is added to the integrated circuit), the capacity of a disk drive is the product of sector size, sectors per track, tracks per side and sides (which in hard disk drives with multiple platters can be greater than 2).

For example, 1.44 MB 3½-inch HD disks have the "M" prefix peculiar to their context, coming from their capacity of 2,880 512-byte sectors (1,440 KiB), consistent with neither a decimal megabyte nor a binary mebibyte (MiB).

[citation needed] The raw maximum transfer rate of 3½-inch ED floppy drives (2.88 MB) is nominally 1,000 kilobits/s, or approximately 83% that of single-speed CD‑ROM (71% of audio CD).

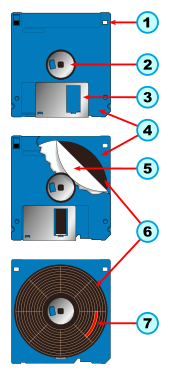

inserted in drive,

(3½-inch floppy diskette,

in front, shown for scale)

- A hole that indicates a high-capacity disk.

- The hub that engages with the drive motor.

- A shutter that protects the surface when removed from the drive.

- The plastic housing.

- A polyester sheet reducing friction against the disk media as it rotates within the housing.

- The magnetic coated plastic disk.

- A schematic representation of one sector of data on the disk; the tracks and sectors are not visible on actual disks.

- The write protection tab (unlabeled) in upper left.