Disney's America

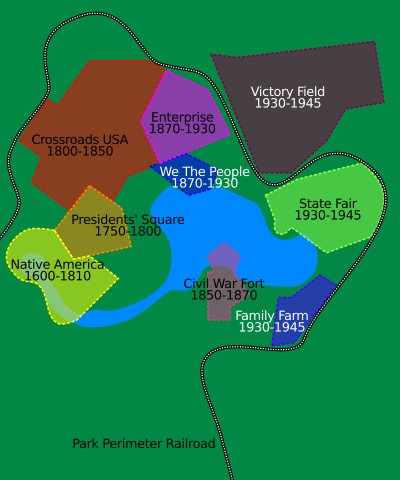

Disney's America would have consisted of nine distinctly-themed areas spanning 125–185 acres (51–75 ha), and it would have featured hotels, housing, a golf course, and nearly 2,000,000 square feet (190,000 m2) of retail and commercial development.

It was cancelled in September 1994 following disappointing early results for Euro Disney (now Disneyland Paris), the death of Frank Wells, rising costs, and the prospect of reduced profits with the park being closed for four months each year.

[6] At the time it was announced on November 11, 1993, Disney had already purchased or held options on the 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) of land needed for the proposed park.

Rummell acknowledged that creating entertainment around historical events such as slavery and the Civil War could be controversial, but he elaborated that "an intelligent story, properly told, shouldn't offend anybody ...

"[7] The location was chosen to tap into the tourist crowds visiting Washington, D.C., and several local attractions, including the battlefield at Manassas, Kings Dominion, Busch Gardens, Jamestown, Yorktown, Colonial Williamsburg, and the Dulles-based Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum.

[13] Although Disney did not ask for concessions at the announcement in November 1993,[7] the company warned the purchase of land options would not proceed without improvements in roads and infrastructure.

[18] Public opposition to the theme park and associated development was stronger than Disney expected, especially from a vocal group of prominent historians named Protect Historic America.

[19] Other members of Protect Historic America included C. Vann Woodward, John Hope Franklin, James M. McPherson, Barbara J.

Fields, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Shelby Foote, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., William Styron, Tom Wicker, Richard Moe and Roger Wilkins.

[23]: 45 Disney also faced opposition from groups concerned that historical events such as the Civil War and slavery could be trivialized by teaching history through entertainment and possibly selling "little souvenir slave ships.

[26] Proponents of the theme park project alleged Protect Historic America was merely a front to advance the interests of wealthy landowners who owned land close to the planned development.

[20] The Disney official in charge of the project, Mark Pacala, penned an editorial touting planned road improvements as benefiting all motorists.

[27] Virginia Transportation Secretary Robert E. Martinez announced the state would seek a full federal review of the planned freeway improvements, which would delay the approval of road construction funds.

[29][30] Disney Vice President John Dreyer dismissed these protesters as stereotypical NIMBY citizens, saying "I think it's very similar to the arguments you've heard about a dozen projects around the country—which is, 'I'm here, I don't want anyone else to come.'

[23]: 47 But even as several representatives promised to take any federal actions to prevent Disney's America from being built near Manassas, Eisner and House Speaker Tom Foley (D-WA) hosted a lunch for Congress members in support of the project.

John Warner (R-VA), Ben Nighthorse Campbell (D-CO), and other officials argued that Congress had no business intervening in what was a state project.

[34][35][36] The same day, a Prince William County judge dismissed a lawsuit that had been brought by Disney's America opponents on the grounds that the proposed park violated local zoning ordinances.

[36] Disney's America not only will not replace historic sites but rather will add to their luster by enthusing our guests about events that occurred there and the people who took part in them.

We plan to use all of the tools available to us -- filmmaking, animation, environments, music, interactive media, live interpretation -- to bring the American experience to life.

Together, we have identified some common themes that run through the American experience -- our persistent resistance to injustice, our quest for tolerance and inclusion, our history of rising to challenges, our faith in the promise of the future and our belief that ordinary people can accomplish extraordinary things.

This is the vision and purpose of Disney's America.Eisner rebuked protesters and detractors, especially the historian members of Protect Historic America, saying in a June 1994 interview with The Washington Post that "I sat through many history classes where I read some of their stuff, and I didn't learn anything.

"[38] Eisner was surprised by the opposition, stating that he had "expected to be taken around on people's shoulders" for both the economic stimulus of 19,000 new jobs and the entertainment value that would allow visitors "to get high on history.

"[42] We remain convinced that a park that celebrates America and an exploration of our heritage is a great idea, and we will continue to work to make it a reality.

[47] The land slated for the proposed park has instead since been used to build tens of thousands of single and multi-family homesites in the Dominion Valley and Piedmont housing developments and Camp William B. Snyder for the Boy Scouts of America.

The main factor was that the Knott family had rejected Disney's bid since they were afraid that the Imagineers would replace much of what their parents had originally built.

Other concepts originally intended for Disney's America were slightly re-themed and re-worked as elements of Disney California Adventure, including the Bountiful Valley Farm (Family Farm), Grizzly River Run (Lewis and Clark Expedition raft ride), California Screamin' (State Fair roller coaster ride) as well as Condor Flats (Victory Field).