Diversity in early Christian theology

This view was challenged by the publication of Walter Bauer's Rechtgläubigkeit und Ketzerei im ältesten Christentum ("Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity") in 1934.

Some scholars clearly support Bauer's conclusions and others express concerns about his "attacking [of] orthodox sources with inquisitional zeal and exploiting to a nearly absurd extent the argument from silence.

[3] One of the discussions among scholars of early Christianity in the past century is to what extent it is appropriate to speak of "orthodoxy" and "heresy".

During the 1970s, increasing focus on the effect of social, political and economic circumstances on the formation of early Christianity occurred as Bauer's work found a wider audience.

However, some feel that instead of an even and neutral approach to historical analysis that the heterodox sects are given an assumption of superiority over the orthodox (or proto-orthodox) movement.

While it is difficult to summarize all current views, general statements may be made, remembering that such broad strokes will have exceptions in specific cases.

[8] While the 27 books that became the New Testament canon present Jesus as fully human,[9][10] Adoptionists (who may have used non-canonical gospels) in addition excluded any miraculous origin for him, seeing him as simply the child of Joseph and Mary, born of them in the normal way.

[11] Some scholars regard a non-canonical gospel used by the Ebionites, now lost except for fragments quoted in the Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis,[12] as the first to be written,[13][14][15] and believe Adoptionist theology may predate the New Testament.

These words from Psalm 2 are also used twice in the canonical Epistle to the Hebrews,[20] which on the contrary presents Jesus as the Son "through whom (God) made the universe.

"[21] The Adoptionist view was later developed by adherents of the form of Monarchianism that is represented by Theodotus of Byzantium and Paul of Samosata.

Arianism, declared by the Council of Nicaea to be heresy, denied the full divinity of Jesus Christ, and is so called after its leader Arius.

[25] Because of the agitation aroused by the dispute,[23] Emperor Constantine I sent Hosius of Córdoba to Alexandria to attempt a settlement; but the mission failed.

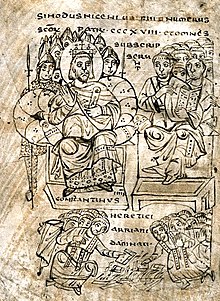

[25] Accordingly, in 325, Constantine convened the First Council of Nicaea, which, largely through the influence of Athanasius of Alexandria, then a deacon but destined to be Alexander's successor, defined the co-eternity and coequality of the Father and the Son, using the now famous term homoousios to express the oneness of their being, while Arius and some bishops who supported him, including Eusebius, were banished.

One such sect, that of the Simonians, was said to have been founded by Simon Magus, the Samaritan who is mentioned in the 1st-century Acts 8:9–24 and who figures prominently in several apocryphal and heresiological accounts by Early Christian writers, who regarded him as the source of all heresies.

Valentinus and other Christian gnostics identified Jesus as the Savior, a spirit sent from the true God into the material world to liberate the souls trapped there.

In Mandaeist Gnosticism, Mandaeans maintain that Jesus was a mšiha kdaba or "false messiah" who perverted the teachings entrusted to him by John the Baptist.

[33] A modern view has argued that Marcionism is mistakenly reckoned among the Gnostics, and really represents a fourth interpretation of the significance of Jesus.

Traveling in his native Anatolia, he and two women preached a return to primitive Christian simplicity, prophecy, celibacy, and asceticism.

[24] Montanus's followers revered him as the Paraclete that Christ had promised, and he led his sect out into a field to meet the New Jerusalem.