Divine Comedy

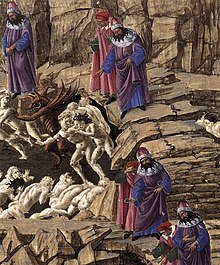

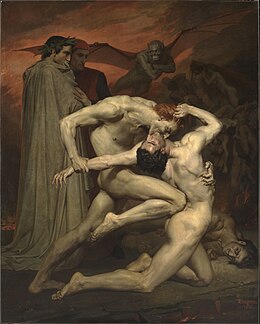

The poem discusses "the state of the soul after death and presents an image of divine justice meted out as due punishment or reward",[3] and describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven.

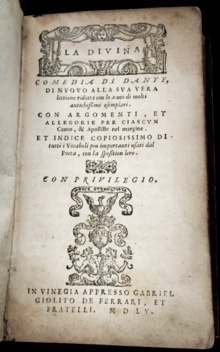

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa (pronounced [komeˈdiːa], Tuscan for "Comedy") – so also in the first printed edition, published in 1472 – later adjusted to the modern Italian Commedia.

The Divine Comedy is composed of 14,233 lines that are divided into three cantiche (singular cantica) – Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) – each consisting of 33 cantos (Italian plural canti).

Written in the first person, the poem tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300.

[11] Beatrice was a Florentine woman he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the mode of the then-fashionable courtly love tradition, which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova.

The poem begins on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300, "halfway along our life's path" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita).

Dante is thirty-five years old, half of the biblical lifespan of seventy (Psalms 89:10, Vulgate), lost in a dark wood (understood as sin),[16][17][18] assailed by beasts (a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf) he cannot evade and unable to find the "straight way" (diritta via) to salvation (symbolised by the sun behind the mountain).

Conscious that he is ruining himself and that he is falling into a "low place" (basso loco) where the sun is silent ('l sol tace), Dante is at last rescued by Virgil, and the two of them begin their journey to the underworld.

During the poem, Dante discusses the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various time zones of the Earth.

The seven subdivided into three are raised further by two more categories: the eighth sphere of the fixed stars that contain those who achieved the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love, and represent the Church Triumphant – the total perfection of humanity, cleansed of all the sins and carrying all the virtues of heaven; and the ninth circle, or Primum Mobile (corresponding to the geocentricism of medieval astronomy), which contains the angels, creatures never poisoned by original sin.

The first complete translation of the Comedy was made into Latin prose by Giovanni da Serravalle in 1416 for two English bishops, Robert Hallam and Nicholas Bubwith, and an Italian cardinal, Amedeo di Saluzzo.

The poem is often lauded for its particularly human qualities: Dante's skillful delineation of the characters he encounters in Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise; his bitter denunciations of Florentine and Italian politics; and his powerful poetic imagination.

Dante was one of the first in the Middle Ages to write of a serious subject, the Redemption of humanity, in the low and "vulgar" Italian language and not the Latin one might expect for such a serious topic.

[42] Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120).

[45] Without access to the works of Homer, Dante used Virgil, Lucan, Ovid, and Statius as the models for the style, history, and mythology of the Comedy.

[46] This is most obvious in the case of Virgil, who appears as a mentor character throughout the first two canticles and who has his epic, the Aeneid, praised with language Dante reserves elsewhere for Scripture.

[50] Dante even acknowledges Aristotle's influence explicitly in the poem, specifically when Virgil justifies the Inferno's structure by citing the Nicomachean Ethics.

[54][55] This influence is most pronounced in the Paradiso, where the text's portrayals of God, the beatific vision, and substantial forms all align with scholastic doctrine.

[56] It is also in the Paradiso that Aquinas and fellow scholastic St. Bonaventure appear as characters, introducing Dante to all of Heaven's wisest souls.

Of the twelve wise men Dante meets in Canto X of the Paradiso, Thomas Aquinas and, even more so, Siger of Brabant were strongly influenced by Arabic commentators on Aristotle.

Philosopher Frederick Copleston argued in 1950 that Dante's respectful treatment of Averroes, Avicenna, and Siger of Brabant indicates his acknowledgement of a "considerable debt" to Islamic philosophy.

Palacios argued that Dante derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter from the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi and from the Isra and Mi'raj, or night journey of Muhammad to heaven.

The 20th-century Orientalist Francesco Gabrieli expressed skepticism regarding the claimed similarities, and the lack of evidence of a vehicle through which it could have been transmitted to Dante.

[65] The Italian philologist Maria Corti pointed out that, during his stay at the court of Alfonso X, Dante's mentor Brunetto Latini met Bonaventura de Siena, a Tuscan who had translated the Kitab al Miraj from Arabic into Latin.

[67] Palacios' theory that Dante was influenced by Ibn Arabi was satirised by the Turkish academic Orhan Pamuk in his novel The Black Book.

[68] In addition to that, it has been claimed that Risālat al-Ghufrān ("The Epistle of Forgiveness"), a satirical work mixing Arabic poetry and prose written by Abu al-ʿAlaʾ al-Maʿarri around 1033 CE, had an influence on, or even inspired, Dante's Divine Comedy.

Although recognised as a masterpiece in the centuries immediately following its publication,[71] the work largely fell into obscurity during the Enlightenment, with some notable exceptions: Vittorio Alfieri; Antoine de Rivarol, who translated the Inferno into French; and Giambattista Vico, who in the Scienza nuova and in the Giudizio su Dante inaugurated what would later become the romantic reappraisal of Dante, juxtaposing him to Homer.

In Russia, beyond Alexander Pushkin's translation of a few tercets,[75] Osip Mandelstam's late poetry has been said to bear the mark of a "tormented meditation" on the Comedy.

[77] Erich Auerbach said Dante was the first writer to depict human beings as the products of a specific time, place and circumstance, as opposed to mythic archetypes or a collection of vices and virtues, concluding that this, along with the fully imagined world of the Divine Comedy, suggests that the Divine Comedy inaugurated literary realism and self-portraiture in modern fiction.

[81] Mendelson's coinage of the term contrasted Dante's initial ostracism with his later importance to Italian national identity, comparing this to the culture-building function of later encyclopedic authors like Shakespeare, Cervantes, or Melville.