Documentary hypothesis

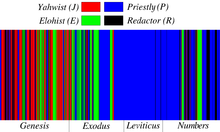

The documentary hypothesis (DH) is one of the models used by biblical scholars to explain the origins and composition of the Torah (or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy).

[5] It posited that the Pentateuch is a compilation of four originally independent documents: the Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, and Priestly sources, frequently referred to by their initials.

[5] This was triggered in large part by the influential publications of John Van Seters, Hans Heinrich Schmid, and Rolf Rendtorff in the mid-1970s,[7] who argued that J was to be dated no earlier than the time of the Babylonian captivity (597–539 BCE),[8] and rejected the existence of a substantial E source.

[12] According to tradition, they were dictated by God to Moses,[13] but when modern critical scholarship began to be applied to the Bible, it was discovered that the Pentateuch was not the unified text one would expect from a single author.

[15][16][Note 2] In the mid-18th century, some scholars started a critical study of doublets (parallel accounts of the same incidents), inconsistencies, and changes in style and vocabulary in the Torah.

[15] In 1780, Johann Eichhorn, building on the work of the French doctor and exegete Jean Astruc's "Conjectures" and others, formulated the "older documentary hypothesis": the idea that Genesis was composed by combining two identifiable sources, the Jehovist ("J"; also called the Yahwist) and the Elohist ("E").

[21] The supplementary hypothesis was better able to explain this unity: it maintained that the Torah was made up of a central core document, the Elohist, supplemented by fragments taken from many sources.

[33][34][35] By contrast, scholars such as John Van Seters advocate a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah is the result of two major additions—Yahwist and Priestly—to an existing corpus of work.

[10] The majority of scholars today continue to recognise Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.

[39] The general trend in recent scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, likely completed during the Persian period (539–333 BCE).

[44] Wellhausen used the sources of the Torah as evidence of changes in the history of Israelite religion as it moved (in his opinion) from free, simple and natural to fixed, formal and institutional.

- J: Yahwist (10th–9th century BCE) [ 1 ] [ 2 ]

- E: Elohist (9th century BCE) [ 1 ]

- Dtr1: early (7th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- Dtr2: later (6th century BCE) Deuteronomist historian

- P*: Priestly (6th–5th century BCE) [ 3 ] [ 2 ]

- D†: Deuteronomist

- R: redactor

- DH: Deuteronomistic history (books of Joshua , Judges , Samuel , Kings )