History of ancient Israel and Judah

The earliest documented mention of "Israel" as a people appears on the Merneptah Stele, an ancient Egyptian inscription dating back to around 1208 BCE.

According to the biblical account, the armies of Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem between 589 and 586 BCE, which led to the destruction of Solomon's Temple and the exile of the Jews to Babylon; this event was also recorded in the Babylonian Chronicles.

[9][10] Cyrus' proclamation began the exiles' return to Zion, inaugurating the formative period in which a more distinctive Jewish identity developed in the Persian province of Yehud.

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai Peninsula, and 100 to 150 km east to west between the sea and the Arabian Desert.

[16] Canaan in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.

"[25] This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity, well enough established for the Egyptians to perceive it as a possible challenge, but an ethnic group rather than an organized state.

[28] Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite – collared-rim jars and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites,[29] and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.

[31] Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations.In The Bible Unearthed (2001), Finkelstein and Silberman summarized recent studies.

The discovery of the remains of a dense network of highland villages – all apparently established within the span of few generations – indicated that a dramatic social transformation had taken place in the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE.

According to Israel Finkelstein, after an emergent and large polity was suddenly formed based on the Gibeon-Gibeah plateau and destroyed by Shoshenq I, the biblical Shishak, in the 10th century BCE,[43] a return to small city-states was prevalent in the Southern Levant, but between 950 and 900 BCE another large polity emerged in the northern highlands with its capital eventually at Tirzah, that can be considered the precursor of the Kingdom of Israel.

[4] Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.

[45] In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital,[45] possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I records a series of campaigns directed at the area.

At this time Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon and Aram Damascus in the east for control of Gilead;[45] the Mesha Stele (c. 830 BCE), left by a king of Moab, celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of Omri" (i.e., Israel).

[47] A century later Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722 BCE).

Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates.

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[61] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.

[62] Jerusalem, destroyed but probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the settlements surrounding it, as well as the towns in the former kingdom's western borders, were all devastated as a result of the Babylonian campaign.

[63][64] This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location.

[67] The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"[68] the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.

[73] Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.

[75] Conversely, Avraham Faust writes that archaeological and demographic surveys show that the population of Judah was significantly reduced to barely 10% of what it had been in the time before the exile.

[77] Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by Samaritans, Arabs, and Ammonites.

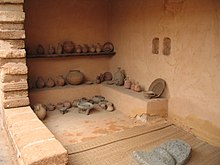

[81][82][page needed][83] In addition to the Temple in Jerusalem, there was public worship practised all over Israel and Judah in shrines and sanctuaries, outdoors, and close to city gates.

In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, the kings Hezekiah and Josiah of Judah implemented a number of significant religious reforms that aimed to centre worship of the God of Israel in Jerusalem and eliminate foreign customs.

Many believe that this quote demonstrates that the early Israelite kingdom followed traditions similar to ancient Mesopotamia, where each major urban centre had a supreme god.

[101] There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the Bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in c. 722 BCE.

Judah at this time was a vassal state of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and around 622 Josiah and his supporters launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone".

[102] According to the Deuteronomists, as scholars call these Judean nationalists, the treaty with Yahweh would enable Israel's god to preserve both the city and the king in return for the people's worship and obedience.

The destruction of Jerusalem, its Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was deeply traumatic and led to revisions of the national mythos during the Babylonian exile.

The national god Yahweh, who selects those to rule his realm and his people, is depicted in the Hebrew Bible as having a hand in the establishment of the royal institution.