Dodola and Perperuna

are rainmaking pagan customs widespread among different peoples in Southeast Europe until the 20th century, found in Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, and Serbia.

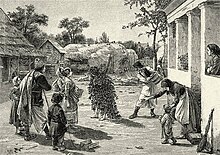

[1][2] The ceremonial ritual is an analogical-imitative magic rite that consists of singing and dancing done by young girls or boys in processions following a main performer who is dressed with fresh branches, leaves and herbs, with the purpose of invoking rain, usually practiced in times of droughts, especially in the summer season, when drought endangers crops and pastures, even human life itself.

Περπερούνα περπατεί / Perperouna perambulates Κή τόν θεό περικαλεί / And to God prays Θέ μου, βρέξε μια βροχή / My God, send a rain Μιἁ βροχή βασιλική / A right royal rain Οσ ἀστἀχυα ς τἀ χωράΦια / That as many (as are there) ears of corn in the fields Τόσα κούτσουρα ς τ ἁμπέλια / So many stems (may spring) on the vines Rainmaking rites are generally called after the divine figure invoked in the ritual songs, as well as the boy or girl who perform the rite, who are called with different names among different peoples (South Slavs, Albanians, Greeks, Hungarians, Moldovans, Romanians, Vlachs or Aromanians, including regions of Bukovina and Bessarabia).

[5][14][15] Those with root "peper-", "papar-" and "pirpir-" were changed accordingly modern words for pepper-tree and poppy plant,[5][16] possibly also perper and else.

[28] The uncertainty of the etymologies provided by scholars leads to a call for a "detailed and in-depth comparative analysis of formulas, set phrases and patterns of imagery in rainmaking songs from all the Balkan languages".

[32][33][34][35] William Shedden-Ralston noted that Jacob Grimm thought Perperuna/Dodola were "originally identical with the Bavarian Wasservogel and the Austrian Pfingstkönig" rituals.

[36] Ancient rainmaking practices have been widespread Mediterranean traditions, already documented in the Balkans since Minoan and Mycenaean times.

[37][38] There is a lack of any strong historical evidence for a link between the figures and practices of the ancient times and those that survided to the end of the 20th century, however, according to Richard Berengarten, if seen as "typologically parallel" practices in the ancient world, they may be interpretable at least as forerunners, even if not as direct progenitors of the modern Balkan rainmaking customs.

It has parallels in ritual prayers for bringing rain in times of drought dedicated to rain-thunder deity Parjanya recorded in the Vedas and Baltic thunder-god Perkūnas, cognates alongside Perun of Proto-Indo-European weather-god Perkwunos.

[5][54] Serbo-Croatian archaic variant Prporuša and verb prporiti se ("to fight") also have parallels in Old Russian ("porъprjutъsja").

[24] Another explanation for the variations of the name Dodola is relation to the Slavic spring goddess (Dido-)Lada/Lado/Lela,[36] some scholars relate Dodole with pagan custom and songs of Lade (Ladarice) in Hrvatsko Zagorje (so-called "Ladarice Dodolske"),[59][60][61] and in Žumberak-Križevci for the Preperuša custom was also used term Ladekarice.

[62][63] Other scholars like Vitomir Belaj, due to the geographical distribution, consider that the rainmaking ritual could also have Paleo-Balkan origin,[64][65] or formed separate of worship of Perun but could be etymologically related.

[70] The Romanian-Aromanian and Greek ethnic origin was previously rejected by Alan Wace, Maurice Scott Thompson, George Frederick Abbott among others.

[71] Perperuna and Dodola are considered very similar pagan customs with common origin,[72][73] with main difference being in the most common gender of the central character (possibly related to social hierarchy of the specific ethnic or regional group[74]), lyric verses, sometimes religious content, and presence or absence of a chorus.

[75] They essentially belong to rituals related to fertility, but over time differentiated to a specific form connected with water and vegetation.

[82] The first written mentions and descriptions of the pagan custom are from the 18th century by Dimitrie Cantemir in Descriptio Moldaviae (1714/1771, Papaluga),[9][83] then in a Greek law book from Bucharest (1765, it invoked 62nd Cannon to stop the custom of Paparuda),[9][84] and by the Bulgarian hieromonk Spiridon Gabrovski who also noted to be related to Perun (1792, Peperud).

[65][85] South Slavs and non-Slavic peoples alike used to organise the Perperuna/Dodola ritual in times of spring and especially summer droughts, where they worshipped the god/goddess and prayed to him/her for rain (and fertility, later also asked for other field and house blessings).

They would be naked, but were not anymore in latest forms of 19-20th century, wearing a skirt and dress densely made of fresh green knitted vines, leaves and flowers of Sambucus nigra, Sambucus ebulus, Clematis flammula, Clematis vitalba, fern and other deciduous shrubs and vines, small branches of Tilia, Oak and other.

They whirled and were followed by a small procession of children who walked and danced with them around the same village and fields, sometimes carrying oak or beech branches, singing the ritual prayer, stopping together at every house yard, where the hosts would sprinkle water on chosen boy/girl who would shake and thus sprinkle everyone and everything around it (example of "analogical magic"[9]), hosts also gifted treats (bread, eggs, cheese, sausages etc., in a later period also money) to children who shared and consumed them among them and sometimes even hosts would drink wine, seemingly as a sacrifice in Perun's honor.

[94][95] By the 20th century once common rituals almost vanished in the Balkans, although rare examples of practice can be traced until 1950-1980s and remained in folk memory.

[1][2] The main reason is the development of agriculture and consequently lack of practical need for existence of mystical connection and customs with nature and weather.

In the old days, Prporuša were very much like a pious ritual, only later the leaders - Prpac - began to boast too much, and Prporuše seemed to be more interested in gifts than beautiful singing and prayer".

[97][98][100][101][102] Due to Anti-Romani sentiment, the association with Romani also caused repulsion, shame and ignorance among last generations of members of ethnic groups who originally performed it.

[86] On island of Krk was also known as Barburuša/Barbaruša/Bambaruša (occurrence there is possibly related to the 15th century migration which included besides Croats also Vlach-Istro-Romanian shepherds[109]).

[110][111] It was also widespread in Dalmatia (especially Zadar hinterland, coast and islands), Žumberak (also known as Pepeluše, Prepelice[96]) and Western Slavonia (Križevci).

[117] According to Natko Nodilo the discrepancy in distribution between these two countries makes an idea that originally Perperuna was Croatian while Dodola was Serbian custom.

[118] Seemingly it was not present in Slovenia, Northern Croatia, almost all of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro (only sporadically in Boka Kotorska).

[121] Letela e peperuda Daĭ, Bozhe, dŭzhd Daĭ, Bozhe, dŭzhd Ot orache na kopache Da se rodi zhito, proso Zhito, proso i pshenitsa Da se ranyat siracheta Siracheta, siromasi Rona-rona, Peperona Bjerë shi ndë arat tona!

Prporuše hodile Slavu Boga molile I šenice bilice Svake dobre sričice Bog nan ga daj Jedan tihi daž!

I dicu poženili / Struni bojžu rosicu Skupi, Bože, oblake / Na tu svetu zemljicu!