Domestication

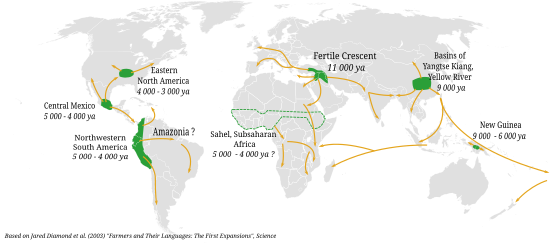

The domestication of plants began around 13,000–11,000 years ago with cereals such as wheat and barley in the Middle East, alongside crops such as lentil, pea, chickpea, and flax.

Beginning around 10,000 years ago, Indigenous peoples in the Americas began to cultivate peanuts, squash, maize, potatoes, cotton, and cassava.

Three groups of insects, namely ambrosia beetles, leafcutter ants, and fungus-growing termites have independently domesticated species of fungi, on which they feed.

[7] Michael D. Purugganan notes that domestication has been hard to define, despite the "instinctual consensus" that it means "the plants and animals found under the care of humans that provide us with benefits and which have evolved under our control.

The changes include increased docility and tameness, coat coloration, reductions in tooth size, craniofacial morphology, ear and tail form (e.g., floppy ears), estrus cycles, levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone and neurotransmitters, prolongations in juvenile behavior, and reductions in brain size and of particular brain regions.

The domestication of animals and plants was triggered by the climatic and environmental changes that occurred after the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum and which continue to this present day.

[1] The Younger Dryas 12,900 years ago was a period of intense cold and aridity that put pressure on humans to intensify their foraging strategies but did not favour agriculture.

In East Asia 8,000 years ago, pigs were domesticated from wild boar genetically different from those found in the Fertile Crescent.

[1] The cat was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent, perhaps 10,000 years ago,[22] from European wildcats, possibly to control rodents that were damaging stored food.

[40] The archaeological and genetic data suggest that long-term bidirectional gene flow between wild and domestic stocks – such as in donkeys, horses, New and Old World camelids, goats, sheep, and pigs – was common.

Domesticated birds principally mean poultry, raised for meat and eggs:[46] some Galliformes (chicken, turkey, guineafowl) and Anseriformes (waterfowl: ducks, geese, and swans).

[17][49] Several other invertebrates have been domesticated, both terrestrial and aquatic, including some such as Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies and the freshwater cnidarian Hydra for research into genetics and physiology.

The phyla involved are Cnidaria, Platyhelminthes (for biological pest control), Annelida, Mollusca, Arthropoda (marine crustaceans as well as insects and spiders), and Echinodermata.

Several parasitic or parasitoidal insects, including the fly Eucelatoria, the beetle Chrysolina, and the wasp Aphytis are raised for biological control.

[14] The founder crops of the West Asian Neolithic included cereals (emmer, einkorn wheat, barley), pulses (lentil, pea, chickpea, bitter vetch), and flax.

[55][56] Sorghum was widely cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa,[57] while peanuts,[58] squash,[58][59] cotton,[58] maize,[60] potatoes,[61] and cassava[62] were domesticated in the Americas.

[58] Continued domestication was gradual and geographically diffuse – happening in many small steps and spread over a wide area – on the evidence of both archaeology and genetics.

[69] Farmers did select for reduced bitterness and lower toxicity and for food quality, which likely increased crop palatability to herbivores as to humans.

[69] However, a survey of 29 plant domestications found that crops were as well-defended against two major insect pests (beet armyworm and green peach aphid) both chemically (e.g. with bitter substances) and morphologically (e.g. with toughness) as their wild ancestors.

These steps are large and essentially instantaneous changes to the genome and the epigenome, enabling a rapid evolutionary response to artificial selection.

For example, cattle have given humanity various viral poxes, measles, and tuberculosis; pigs and ducks have contributed influenza; and horses have brought the rhinoviruses.

Anarcho-primitivism critiques domestication as destroying the supposed primitive state of harmony with nature in hunter-gatherer societies, and replacing it, possibly violently or by enslavement, with a social hierarchy as property and power emerged.

This, in turn, he argues, corrupted human ethics and paved the way for "conquest, extermination, displacement, repression, coerced and enslaved servitude, gender subordination and sexual exploitation, and hunger.

"[94] Domesticated ecosystems provide food, reduce predator and natural dangers, and promote commerce, but their creation has resulted in habitat alteration or loss, and multiple extinctions commencing in the Late Pleistocene.

[98][99] Mutational load can be increased by reduced selective pressure against moderately harmful traits when reproductive fitness is controlled by human management.

[25] However, there is evidence against a bottleneck in crops, such as barley, maize, and sorghum, where genetic diversity slowly declined rather than showing a rapid initial fall at the point of domestication.

[8][100] Ambrosia beetles in the weevil subfamilies Scolytinae and Platypodinae excavate tunnels in dead or stressed trees into which they introduce fungal gardens, their sole source of nutrition.

[101] Symbiotic fungi produce and detoxify ethanol, which is an attractant for ambrosia beetles and likely prevents the growth of antagonistic pathogens and selects for other beneficial symbionts.