Doomsday argument

The argument was subsequently championed by the philosopher John A. Leslie and has since been independently conceived by J. Richard Gott[2] and Holger Bech Nielsen.

A more general form was given earlier in the Lindy effect,[4] which proposes that for certain phenomena, the future life expectancy is proportional to (though not necessarily equal to) the current age and is based on a decreasing mortality rate over time.

Depending on the projection of the world population in the forthcoming centuries, estimates may vary, but the argument states that it is unlikely that more than 1.2 trillion humans will ever live.

It is possible to sum the probabilities for each value of N and, therefore, to compute a statistical 'confidence limit' on N. For example, taking the numbers above, it is 99% certain that N is smaller than 6 trillion.

Gott specifically proposes the functional form for the prior distribution of the number of people who will ever be born (N).

Gott's DA used the vague prior distribution: where Since Gott specifies the prior distribution of total humans, P(N), Bayes' theorem and the principle of indifference alone give us P(N|n), the probability of N humans being born if n is a random draw from N: This is Bayes' theorem for the posterior probability of the total population ever born of N, conditioned on population born thus far of n. Now, using the indifference principle: The unconditioned n distribution of the current population is identical to the vague prior N probability density function,[note 1] so: giving P (N | n) for each specific N (through a substitution into the posterior probability equation): The easiest way to produce the doomsday estimate with a given confidence (say 95%) is to pretend that N is a continuous variable (since it is very large) and integrate over the probability density from N = n to N = Z.

This was much higher than the temporal confidence bound produced by counting births, because it applied the principle of indifference to time.

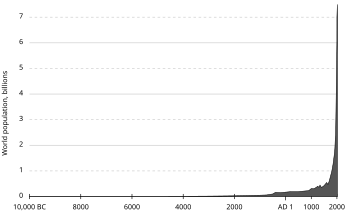

Heinz von Foerster argued that humanity's abilities to construct societies, civilizations and technologies do not result in self-inhibition.

Von Foerster found that this model fits some 25 data points from the birth of Jesus to 1958, with only 7% of the variance left unexplained.

The most remarkable thing about von Foerster's model was it predicted that the human population would reach infinity or a mathematical singularity, on Friday, November 13, 2026.

The "standard" doomsday argument hypothesis skips over this point entirely, merely stating that the reference class is the number of "people".

According to Nick Bostrom, consciousness is (part of) the discriminator between what is in and what is out of the reference class, and therefore extraterrestrial intelligence might have a significant impact on the calculation.

[citation needed] The following sub-sections relate to different suggested reference classes, each of which has had the standard doomsday argument applied to it.

If the "reference class" is the set of humans to ever be born, this gives N < 20n with 95% confidence (the standard doomsday argument).

Robin Hanson's paper sums up these criticisms of the doomsday argument:[9] All else is not equal; we have good reasons for thinking we are not randomly selected humans from all who will ever live.The a posteriori observation that extinction level events are rare could be offered as evidence that the doomsday argument's predictions are implausible; typically, extinctions of dominant species happen less often than once in a million years.

In Bayesian terms, this response to the doomsday argument says that our knowledge of history (or ability to prevent disaster) produces a prior marginal for N with a minimum value in the trillions.

This is an equally impeccable Bayesian calculation, rejecting the Copernican principle because we must be 'special observers' since there is no likely mechanism for humanity to go extinct within the next hundred thousand years.

This response is accused of overlooking the technological threats to humanity's survival, to which earlier life was not subject, and is specifically rejected by most[by whom?

If q is large, then our 95% confidence upper bound is on the uniform draw, not the exponential value of N. The simplest way to compare this with Gott's Bayesian argument is to flatten the distribution from the vague prior by having the probability fall off more slowly with N (than inverse proportionally).

are improper priors, this applies to Gott's vague-prior distribution also, and they can all be converted to produce proper integrals by postulating a finite upper population limit.)

[13] The Bayesian argument by Carlton M. Caves states that the uniform distribution assumption is incompatible with the Copernican principle, not a consequence of it.

)Although this example exposes a weakness in J. Richard Gott's "Copernicus method" DA (that he does not specify when the "Copernicus method" can be applied) it is not precisely analogous with the modern DA[clarification needed]; epistemological refinements of Gott's argument by philosophers such as Nick Bostrom specify that: Careful DA variants specified with this rule aren't shown implausible by Caves' "Old Lady" example above, because the woman's age is given prior to the estimate of her lifespan.

Since human age gives an estimate of survival time (via actuarial tables) Caves' Birthday party age-estimate could not fall into the class of DA problems defined with this proviso.

To produce a comparable "Birthday Party Example" of the carefully specified Bayesian DA, we would need to completely exclude all prior knowledge of likely human life spans; in principle this could be done (e.g.: hypothetical Amnesia chamber).

Without knowing the lady's age, the DA reasoning produces a rule to convert the birthday (n) into a maximum lifespan with 50% confidence (N).

Western demographics are now fairly uniform across ages, so a random birthday (n) could be (very roughly) approximated by a U(0,M] draw where M is the maximum lifespan in the census.

The other half of the time 2n underestimates M, and in this case (the one Caves highlights in his example) the subject will die before the 2n estimate is reached.

Some philosophers have suggested that only people who have contemplated the doomsday argument (DA) belong in the reference class "human".

An attendant could have argued thus: Presently, only one person in the world understands the Doomsday argument, so by its own logic there is a 95% chance that it is a minor problem which will only ever interest twenty people, and I should ignore it.Jeff Dewynne and Professor Peter Landsberg suggested that this line of reasoning will create a paradox for the doomsday argument:[10] If a member of the Royal Society did pass such a comment, it would indicate that they understood the DA sufficiently well that in fact 2 people could be considered to understand it, and thus there would be a 5% chance that 40 or more people would actually be interested.

In both cases, he concludes that the doomsday argument's claim, that there is a "Bayesian shift" in favor of the shorter future duration, is fallacious.