Doping at the Tour de France

Cycling, having been from the start a sport of extremes, whether of speed by being paced by tandems, motorcycles and even cars, or of distance, the suffering involved encouraged the means to alleviate it.

[8] The American specialist in doping, Max M. Novich, wrote: "Trainers of the old school who supplied treatments which had cocaine as their base declared with assurance that a rider tired by a six-day race would get his second breath after absorbing these mixtures.

Henri Pélissier explained the problem – whether or not he had the right to take off a jersey – and went on to talk of drugs, reported in Londres' race diary, in which he coined the phrase Les Forçats de la Route (The Convicts of the Road): Henri spoke of being as white as shrouds once the dirt of the day had been washed off, then of their bodies being drained by diarrhoea, before continuing: Francis Pélissier said much later: "Londres was a famous reporter but he didn't know about cycling.

He spoke of "medicine from the heart of Africa... healers laying on hands or giving out irradiating balms, feet plunged into unbelievable mixtures which could lead to eczema, so-called magnetised diets and everything else you could imagine.

"[21] Such was the extent to which stronger drugs entered cycling that the French team manager, Marcel Bidot, was cited to an inquiry by the Council of Europe as saying: "Three-quarters of riders were doped.

In 1960, Pierre Dumas walked into a hotel bedroom on his nightly tour of teams to find eventual winner Gastone Nencini prone on his bed with a plastic tube running from each arm to a bottle containing hormones.

Ten kilometres from the summit, said the journalist Jacques Augendre, French rider Jean Malléjac was: "Streaming with sweat, haggard and comatose, he was zigzagging and the road wasn't wide enough for him...

In the 1960 Tour, Roger Rivière was second to the Italian Gastone Nencini, a rider he planned to beat by tagging along with him in the mountains and then speeding away on the flat.

Rivière quickly passed the blame for his fall and his broken back on the team mechanic, accusing him of leaving oil on the wheels and the brakes for not working.

Jacques Goddet wrote that he suspected doping but nothing was proven – other than that none of the hotels the previous night had served fish, the hoteliers being anxious to clear their reputation.

In 1960, the Danish rider Knud Enemark Jensen collapsed during the 100 km team time trial at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome and died later in hospital.

[20] Alec Taylor, team manager of rider Tom Simpson who died following doping usage in the 1967 Tour, said officials treated controls in fear, knowing what was there, afraid of what they might find.

[citation needed] About two kilometres from the summit of the day's main climb, Mont Ventoux, Simpson began to zig-zag across the road, eventually falling against an embankment.

[citation needed] A motorcycle policeman summoned Pierre Dumas, who took over team officials' first attempts at saving Simpson, including mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

[citation needed] Drug usage was only hinted at in the news coverage, particularly by Jacques Goddet, who referred in L'Équipe to Simpson's "errors in the way he looked after himself."

The following month, Manning went further, in a piece headed "Evidence in the case of Simpson who crossed the frontier of endurance without being able to know he had 'had enough'": During 1974, a number of riders failed tests for amphetamines, including Claude Tollet at the Tour.

According to Dr Jean-Pierre de Mondenard, steroids were not used to build muscle bulk, but rather to improve recovery and thereby let competitors train harder and longer and with less rest.

When Gutierrez went to provide his sample, the doctor – a man called Le Calvez spending his first day with the race – grew suspicious and tugged up his jersey, revealing a system of tubes and a bottle of urine.

At 8pm, the organiser, Félix Lévitan, told the press that the UCI had ruled that Pollentier would be fined 5,000 Swiss francs and start an immediate suspension of two months.

[37] On 8 July 1998, French Customs arrested Willy Voet, a soigneur for the Festina team, for the possession of illegal drugs, including narcotics, erythropoietin (EPO), growth hormones, testosterone, and amphetamines.

In June, British cyclist David Millar, also of Cofidis, and time trial world champion, was detained by French police, his apartment searched and two used EPO syringes found.

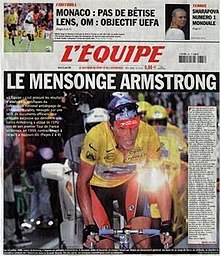

On 22 October 2012, Armstrong was banned for life and stripped of all his titles since 1 August 1998, including all seven of his Tour de France victories, because an investigation by USADA concluded that he had been engaged in a massive doping scheme.

Of the cyclists who finished on the podium in the era in which Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France seven times (1999–2005), Fernando Escartín is the sole rider not to be implicated in a doping scandal.

In 2006, several riders, including Jan Ullrich and Ivan Basso, were barred from the eve of the race amid allegations by Spanish police as a result of their Operación Puerto investigation.

[44] The Astana-Würth team could not start because, despite a ruling by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, five of its nine Tour riders were barred after being officially named in the Operacion Puerto affair.

[56] Then on 24 July it was revealed that Alexander Vinokourov had failed a test for blood doping after the time trial in Albi, which he won by more than a minute[57] As a result, the Astana Team withdrew.

[58] A day later, after winning the 16th stage on the Col d'Aubisque—a victory that assured he would be the overall winner—it was alleged that Rasmussen had lied to his Rabobank team about his whereabouts on 13 and 14 June, prior to the Tour.

[62] Tour winner Alberto Contador also continued to be linked to doping allegations, focussing on his relationship with Eufemiano Fuentes and his role in Operación Puerto, but without new revelations.

The report contained affidavits from the following riders, each of whom described widespread use by Tour racers of banned substances such as Erythropoietin (EPO), transfused blood, and testosterone.

[77][78][79] Landis also maintains that he witnessed Armstrong receiving multiple blood transfusions, and dispensing testosterone patches to his teammates on the United States Postal Service Team.