Dorgon

Dorgon also introduced the policy of forcing all Han Chinese men to shave the front of the heads and wear their hair in queues just like the Manchus.

Dorgon was one of the most influential among Nurhaci's sons, and his role was instrumental to the Qing occupation of Beijing, the capital of the fallen Ming dynasty, in 1644.

The conflict was resolved with a compromise – both backed out, and Hong Taiji's ninth son, Fulin, ascended the throne as the Shunzhi Emperor.

It was rumoured that Dorgon had a romantic affair with the Shunzhi Emperor's mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, and even secretly married her, but there are also refutations.

[3] On 17 February 1644, Jirgalang, who was a capable military leader but appeared uninterested in managing state affairs, willingly yielded control of all official matters to Dorgon.

[9] The last obstacle between Dorgon and Beijing was Wu Sangui, a former Ming general guarding the Shanhai Pass at the eastern end of the Great Wall.

[14] After six weeks of mistreatment at the hands of rebel troops, the residents of Beijing sent a party of elders and officials to greet their liberators on 5 June.

[15] They were startled when, instead of meeting Wu Sangui and the Ming heir apparent, they saw Dorgon, a horse-riding Manchu with the front half of his head shaved, present himself as the Prince-Regent.

[16] In the midst of this upheaval, Dorgon installed himself as Prince-Regent in Wuying Palace (武英殿), the only building that remained more or less intact after Li Zicheng had set fire to the Forbidden City on 3 June.

[27] In June 1645, Dorgon eventually decreed that all official documents should refer to him as "Imperial Uncle Prince Regent" (皇叔父攝政王), leaving him one step short of claiming the throne for himself.

[29] To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree from the Shunzhi Emperor allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners or the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners, it was only later in the Qing dynasty that these policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.

"[34] Despite tax remissions and large-scale building programmes designed to facilitate the transition, in 1648 many Chinese civilians still lived among the newly arrived Banner population and there was still animosity between the two groups.

"[38] Under the Shunzhi Emperor's reign, the average number of graduates of the metropolitan examination per session was the highest of the Qing dynasty ("to win more Chinese support"), continuing until 1660 when lower quotas were established.

[42] From newly captured Xi'an, in early April 1645, the Qing forces mounted a campaign against the rich commercial and agricultural region of Jiangnan south of the lower Yangtze River, where in June 1644 the Prince of Fu had established a regime loyal to the Ming.

[49] On 21 July 1645, after Jiangnan had been superficially pacified, Dorgon issued a most inopportune edict ordering all Han Chinese men to shave the front half of their heads and wear the rest of their hair in queues identical to those of the Manchus.

When the city walls were finally breached on 9 October 1645, the Qing army led by the previous Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐; d. 1667) massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.

[57] A few committed loyalists became hermits, hoping that for lack of military success, their withdrawal from the world would at least symbolise their continued defiance against Qing rule.

[59] In July 1646, a new southern campaign led by Bolo sent Prince Lu's Zhejiang court into disarray and proceeded to attack the Longwu regime in Fujian.

[62] The two Ming regimes fought each other until 20 January 1647, when a small Qing force led by Li Chengdong captured Guangzhou, killed the Shaowu Emperor, and sent the Yongli court fleeing to Nanning in Guangxi.

[63] In May 1648, however, Li mutinied against the Qing Empire, and the concurrent rebellion of another former Ming general in Jiangxi helped the Yongli Emperor to retake most of south China.

[65] Finally on 24 November 1650, Qing forces led by Shang Kexi captured Guangzhou and massacred the city's population, killing as many as 70,000 people.

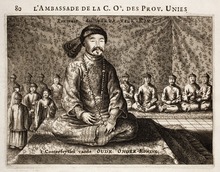

[66] Although Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof who witnessed the event happened claimed only 8000 people were slaughtered[67][68] Meanwhile, in October 1646, Qing armies led by Hooge reached Sichuan, where their mission was to destroy the regime of bandit chief Zhang Xianzhong.

[70] Also late in 1646 but further north, forces assembled by a Muslim leader known in Chinese sources as Milayin (米喇印) revolted against Qing rule in Ganzhou (Gansu).

[71] Both Milayin and Ding Guodong were captured and killed by Meng Qiaofang (孟喬芳; 1595–1654) in 1648, and by 1650 the Muslim rebels had been crushed in campaigns that inflicted heavy casualties.

[72]· Dorgon died on 31 December 1650, during a hunting trip in Kharahotun[citation needed] (present-day Chengde, Hebei), after sustaining injuries despite the presence of imperial doctors.

The official Qing history claim that he injured his leg while riding on his horse and that the injuries were so severe that he could not survive the trip back to the Forbidden City, despite the presence of imperial doctors, was dubious at best.

As a Chinese character, Yuan 袁 (Yuen) substantially resembles the word "Gon 袞" as in "Dorgon 多尔袞" in the written form.

After successfully escaping execution, the camouflage to re-emerge as a Han Chinese person was considered perfect, as Yuan 袁 (Yuen) was also the family name of Yuan Chonghuan 袁崇煥 the Han Chinese general who fatally wounded Nurhaci in the 1626 Battle of Ningyuan, making it highly unlikely that pursuing forces from the Forbidden City would suspect that he and/or his descendants were members of the Dorgon clan.

The village where his descendants have sprung up since 1651 was named "Revelation of the Dragon 顯龍", indicating his hope that one day someone in his line would be able to reclaim the throne, which never happened through the remaining years of the Qing dynasty.

[73] These were policies designed to bolster the rule of the Qing conquerors, but which caused considerable disturbance and bloodshed in China, and included: According to the account of Japanese travellers, Dorgon was a 34- or 35-year-old man with slightly dark skin complexion and sharp eyes.