Chinatown, San Francisco

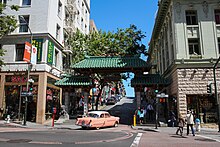

One is Grant Avenue, with the Dragon Gate ("Chinatown Gate" on some maps) at the intersection of Bush Street and Grant Avenue, designed by landscape architects Melvin Lee and Joseph Yee and architect Clayton Lee; Saint Mary's Square with a statue of Sun Yat-sen by Benjamin Bufano;[10] a war memorial to Chinese war veterans; and stores, restaurants and mini-malls that cater mainly to tourists.

The other, Stockton Street, is frequented less often by tourists, and it presents an authentic Chinese look and feel reminiscent of Hong Kong, with its produce and fish markets, stores, and restaurants.

[10] Since it is one of the few open spaces in Chinatown and sits above a large underground parking lot, Portsmouth Square is used by people such as tai chi practitioners and old men playing Chinese chess.

[15] In the 1850s, Chinese pioneers, mainly from villages in the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong, began immigrating in large numbers to San Francisco, initially drawn by the California Gold Rush and the building of the first transcontinental railroad, and settling in Chinatown for refuge from the hostilities in the West.

San Francisco's Chinatown was the port of entry for early Chinese immigrants from the west side of the Pearl River Delta, speaking mainly Hoisanese[23] and Zhongshanese,[20] in the Guangdong province of southern China from the 1850s to the 1900s.

[26]: 34–38 By 1854, the Alta California, a local newspaper which had previously taken a supportive stance on Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, began attacking them, writing after a recent influx that "if the city continues to fill up with these people, it will be ere long become necessary to make them subject of special legislation".

In 1875, the U.S. Congress followed California's action and passed the Page Law, which was the first major legal restriction to prohibit the immigration of Chinese, Japanese, and Mongolian women into America.

[42] Tour providers emphasized the vice-ridden elements of the area, strongly encouraging any curious visitors to take a professional guide or police escort with them to venture into Chinatown.

In 1850, Toy opened a chain of brothels at 34 and 36 Waverly Place[48] (then called Pike Street), importing girls from China in their teens, 20s and 30s, as well as some as young as eleven years old, to work in them.

Her neighbors on Pike Street—conveniently linked to San Francisco's business district by Commercial Street—included the elegant new "parlour house" of madame Belle Cora, and the cottage of Fanny Perrier, mistress of Judge Edward (Ned) McGowan.

From 1868 until her death in 1928, she lived a largely quiet life in Santa Clara County, returning to public attention only upon dying at age 98 in San Jose, three months short of her ninety ninth birthday.

The mostly male Chinese immigrants came to the United States with the intent of sending money home to support their families; coupled with the high cost of repaying their loans for travel, they often had to take any work that was available.

At their height in the 1880s and 1890s, twenty to thirty tongs ran highly profitable gambling houses, brothels, opium dens, and slave trade enterprises in Chinatown.

The day has passed when a progressive city like San Francisco should feel compelled to tolerate in its midst a foreign community, perpetuated in filth, for the curiosity of tourists, the cupidity of lawyers and the adoration of artists.

At the 1901 Chinese Exclusion Convention held in San Francisco, A. Sbarboro called Chinatown "synonymous with disease, dirt and unlawful deeds" that "give[s] us nothing but evil habits and noxious stenches".

"[65] The San Francisco Call reported it as "a vigorous protest" and noted that as the site of the Chinese consulate was the property of Imperial China, it could not be reassigned by the city.

[67] On July 8, 1906, after 25 committee meetings and considering various alternative sites in the city, the subcommittee submitted a final report stating their inability to drive the Chinese from their old Chinatown quarters.

[43] A group of Chinese merchants, including Mendocino-born Look Tin Eli, hired American architects to design in a Chinese-motif "Oriental" style in order to promote tourism in the rebuilt Chinatown.

[31]: 113–115 This design strategy leveraged the ethnic identity and exoticness that city planners used to justify the relocation of Chinatown to become the same forces that made the area an attractive tourist location.

[42][43] In November 1907, an article extolling the virtues of the "new Chinatown of San Francisco" was written, praising the new "substantial, modern, fireproof buildings of brick and stone ... following the Oriental style of architecture" and declaring "[n]o more picturesque squalor, no more gambling dens, opium joints or public haunts of vice" would be tolerated, at the command of the Chinese Six Companies.

Designed by W(alter) D’Arcy Ryan, who also designed the "Path of Gold" streetlights along Market Street,[31]: 124–125 the distinctive 2,750 pounds (1,250 kg) street lamp, painted in traditional Chinese colors of red, gold and green, was composed of a cast-iron hexagonal base supporting a lotus and bamboo shaft surmounted with two cast-aluminum dragons below a pagoda lantern with bells and topped by a stylized hexagonal red roof[77]—all in keeping with the Oriental style pioneered by Look Tin Eli (1910).

Since then, the original molds were used to add 24 more dragon street lamps were in 1996 (distinguishable by the foundry, whose name and location in Emporia, Kansas is cast on an access door at the base), and later, 23 more were added along Pacific by PG&E.

In October 1942, Earl Warren, running for Governor of California, wrote, "Like all native born Californians, I have cherished during my entire life a warm and cordial feeling for the Chinese people."

The Chinese Culture Center is a community based non-profit organization located on the third floor of the Hilton San Francisco Financial District, across Kearny Street from Portsmouth Square.

The Moon Festival is popularly celebrated throughout China and surrounding countries each year, with local bazaars, entertainment, and mooncakes, a pastry filled with sweet bean paste and egg.

Chinatown is frequently the venue of traditional Chinese funeral processions, where a marching band (playing Western songs such as Nearer, My God, to Thee) takes the street with a motorcycle escort.

[104] The band is followed by a car displaying an image of the deceased (akin to the Chinese custom of parading a scroll with his or her name through the village), and the hearse and the mourners, who then usually travel to Colma south of San Francisco for the actual funeral.

Contrary to popular belief, while the Chinese-American writer Amy Tan was inspired by Chinatown and its culture for the basis of her book The Joy Luck Club and the subsequent movie, she did not grow up in this area; she was born and grew up in Oakland.

[113][114] According to the San Francisco Chronicle, activist Rose Pak then "almost single-handedly persuaded the city to build" the $1.5 billion Central Subway project to compensate Chinatown for the demolition of the freeway.

It opened with a soft launch as part of a shuttle service on November 12, 2022, introducing two new metro stations downtown before officially being connected to the T Third Street line on January 7, 2023.