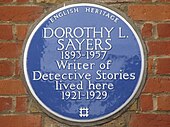

Dorothy L. Sayers

The appointment carried a better stipend than the Christ Church posts and the large rectory had considerably more room than the family's house in Oxford,[8] but the move cut them off from the city's lively social scene.

[9] In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), Catherine Kenney writes that the lack of siblings and neighbouring children of her own age or class made Sayers's childhood fairly solitary, although her parents were loving and attentive.

[11] As an Anglican with strong high-church views, she was repelled by the form of Christianity practised at Godolphin, described by her biographer James Brabazon as "a low-church pietism, drab and mealy-mouthed", which came close to putting her off religion completely.

[4] Later in her time at Oxford, she became attracted to a fellow student named Roy Ridley, later chaplain of Balliol, on whose appearance and manner she later drew for her best-known character, Lord Peter Wimsey.

She had begun writing it before joining Benson's, and it was published in 1923, to mixed reviews; one critic thought it a "somewhat complicated mystery ... clever but crude", and another found the aristocratic Wimsey unconvincing as a detective and the story "a poor specimen of sensationalism".

[39] Some other reviews were more favourable: "the solution does not, as is so often the case, come as an anti-climax to disappoint expectations and lead the reader to feel that he has been 'had' ... We hope to hear from the noble sleuth again";[40] "We had hardly thought a woman writer could be so robustly gruesome ... a very diverting problem";[41] "First-rate construction ... a thoroughly satisfactory yarn from start to finish".

Eustace, a medical practitioner, provided the main plot device and scientific details; Sayers turned them into prose, hoping to write a novel in the manner of the 19th-century author Wilkie Collins, whose work she admired.

In terms of its literary status in relation to more manifestly serious fiction of Sayers's day, Kenney ranks it below the final three Wimsey novels, The Nine Tailors, Gaudy Night and Busman's Honeymoon.

At the BBC's request she created a cycle of twelve radio plays portraying the life of Jesus, The Man Born to Be King (1941–42), which, Kenney observes, were broadcast to "a huge audience of Britons during the darkest days of the Second World War".

[116] Sayers made a last foray into crime fiction in 1953 with No Flowers By Request, another collaborative serial, published in The Daily Sketch, co-written with E. C. R. Lorac, Anthony Gilbert, Gladys Mitchell and Christianna Brand.

[125] According to the literary critic Bernard Benstock, Sayers's reputation as a novelist is based on her works featuring Peter Wimsey, the aristocratic amateur detective who appears in eleven of her twelve novels and four collections of short stories.

[129] The crime writer Julian Symons observes that the growth of the Golden Age writing in Britain during the inter-war years came "not by adherence to the rules but through a measure of revolt against them" by Sayers, Anthony Berkeley and Agatha Christie.

In 1963, in an article in The Listener, the cultural critic Martin Green described Sayers as "one of the world's masters of the pornography of class-distinction", while he outlined Wimsey's treatment of his social inferiors.

[141] The writer Colin Watson in his study of interwar thrillers, Snobbery with Violence, also saw in Wimsey the habit of mocking those from different social classes;[142] for Sayers's descriptions of the wealthy and titled, he described her a "sycophantic bluestocking".

[152] A London critic wrote, "Not only is this play sincere and impressive ... it is good entertainment ... an essentially serious treatment of theological questions ... which with rare skill Miss Sayers has made at the same time dramatic".

[152] According to the historian Lucy Wooding the plays and the books combine a high degree of professional competence with "fresh and penetrating insights into the meaning of the Christian faith in the modern world".

[156] In a 2017 study for the Ecclesiastical History Society, Margaret Wiedemann Hunt writes that The Man Born to Be King was "an astonishing and far-reaching innovation", not only because it used colloquial speech and because Jesus was portrayed by an actor (something not then permitted in theatres in Britain), but also because "it brought the gospels into people's lives in a way that demanded an imaginative response".

[157] In preparation for writing the cycle, Sayers made her own translations of the Gospels from the original Greek into modern English; she hoped to persuade listeners that the 17th-century King James version was over-familiar to churchgoers and incomprehensible to everyone else.

[167] The theological academic Mary Prentice Barrows considers that when the form is used in English translations of Dante, including those by Sayers, "the necessity of fitting the exact sense into triple rhymes inevitably forces distorted syntax and strange choices of words, so that the limpidity—the characteristic beauty of the original—is lost".

[169] The critic Dudley Fitts criticised Sayers's use of terza rima in English, and her use of some archaisms for the sake of rhyme which "are so nearly pervasive that they reduce the impact of a work generously conceived and lovingly elaborated".

Notes were included on each canto to explain the allegories and symbology; the writer Anne Perry considers these "acutely satisfying and thought provoking and infinitely enriching the work".

Philip L. Scowcroft, in a study of her approach to race, cites examples from Unnatural Death such as "The second man ... seemed to wear the long-toed boots affected by Jew boys of the louder sort"; "'God bless my soul', said Sir Charles horrified, 'an English girl in the hands of a nigger.

[177]Scowcroft concludes his examination by saying that although Sayers showed some elements of contemporary attitudes, "the much stronger evidence of her Jewish and foreign characters as they unfold in her books suggest that in the matter of 'racial prejudice', ... she and Lord Peter were more enlightened than the average.

[190]Sayers published no autobiographical work, and told her literary executor, Muriel St Clare Byrne, that she wanted no biography of her to be written until fifty years after her death.

[195] Such books were written without access to Sayers's personal papers, which included a large archive of correspondence, an unpublished memoir of her early years and an unfinished autobiographical novel.

[207] As a reviewer Sayers wrote of one book by a now neglected writer, A. E. Fielding, "The plot is extremely intricate and full of red herrings, and the solution is kept a dark secret up to the last moment.

[208] James notes that Sayers nonetheless wrote within the "Golden Age" conventions,[n 16] with a central mystery, a closed circle of suspects and a solution that the reader can work out by logical deduction from clues "planted with deceptive cunning but essential fairness ... Those were not the days of the swift bash to the skull followed by 60,000 words of psychological insight".

[210] On BBC radio, in numerous adaptations of Sayers's detective stories, Wimsey has been played by more than a dozen actors, including Rex Harrison, Hugh Burden, Alan Wheatley, Ian Carmichael and Gary Bond.

The asteroid was discovered by Luboš Kohoutek, but the name was suggested by the astronomer Brian G. Marsden, with whom Sayers consulted extensively during the last year of her life, in her attempt to rehabilitate the Roman poet Lucan.

[223] The Dorothy L. Sayers Society was founded in 1976 and, as at 2024, continues in its mission "to promote the study of the life, works and thoughts of this great scholar and writer, to encourage the performance of her plays and the publication of books by and about her, to preserve original material for posterity and to provide assistance for researchers".