Druid

*druwides), whose original meaning is traditionally taken to be "oak-knower", based upon the association of druids' beliefs with oak trees, which was made by Pliny the Elder, who also suggested that the word is borrowed from the Greek word δρῦς (drỹs) 'oak tree'[13][10][14][15][16] but nowadays it is more often understood as originally meaning 'one with firm knowledge' (i.e. 'a great sage'),[17][18] as Pliny is the only ancient author drawing the association between oaks and druids[19] and the intensifying modifier sense of the first element fits better with other similar compounds attested in Old Irish (suí 'sage, wise man' < *su-wid-s 'good knower', duí 'idiot, fool' < *du-wid-s 'bad knower', ainb 'ignorant' < *an-wid-s 'not-knower').

In his description, Julius Caesar wrote that they were one of the two most important social groups in the region (alongside the equites, or nobles) and were responsible for organizing worship and sacrifices, divination, and judicial procedure in Gallic, British, and Irish societies.

[24][failed verification] He wrote that they were exempt from military service and from paying taxes, and had the power to excommunicate people from religious festivals, making them social outcasts.

He remarked upon the importance of prophets in druidic ritual: These men predict the future by observing the flight and calls of birds and by the sacrifice of holy animals: all orders of society are in their power ... and in very important matters they prepare a human victim, plunging a dagger into his chest; by observing the way his limbs convulse as he falls and the gushing of his blood, they are able to read the future.Archaeological evidence from western Europe has been widely used to support the theory that Iron Age Celts practiced human sacrifice.

[39] Nora Chadwick, an expert in medieval Welsh and Irish literature who believed the druids to be great philosophers, has also supported the idea that they had not been involved in human sacrifice, and that such accusations were imperialist Roman propaganda.

Subsidiary to the teachings of this main principle, they hold various lectures and discussions on the stars and their movement, on the extent and geographical distribution of the earth, on the different branches of natural philosophy, and on many problems connected with religion.Diodorus Siculus, writing in 36 BCE, described how the druids followed "the Pythagorean doctrine", that human souls "are immortal, and after a prescribed number of years they commence a new life in a new body".

Diogenes Laertius, in the 3rd century CE, wrote that "Druids make their pronouncements by means of riddles and dark sayings, teaching that the gods must be worshipped, and no evil done, and manly behavior maintained".

[43] Druids play a prominent role in Irish folklore, generally serving lords and kings as high ranking priest-counselors with the gift of prophecy and other assorted mystical abilities – the best example of these possibly being Cathbad.

[53] Biróg, another bandruí of the Tuatha Dé Danann, plays a key role in an Irish folktale where the Fomorian warrior Balor attempts to thwart a prophecy foretelling that he would be killed by his own grandson by imprisoning his only daughter Eithne in the tower of Tory Island, away from any contact with men.

[54][55] Bé Chuille (daughter of the woodland goddess Flidais, and sometimes described as a sorceress rather than a bandruí) features in a tale from the Metrical Dindshenchas, where she joins three other of the Tuatha Dé to defeat the evil Greek witch Carman.

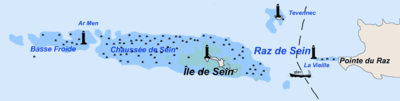

[53] According to classical authors, the Gallizenae (or Gallisenae) were virgin priestesses of the Île de Sein off Pointe du Raz, Finistère, western Brittany.

[59] According to Pomponius Mela, the Gallizenae acted as both councilors and practitioners of the healing arts: Sena, in the Britannic Sea, opposite the coast of the Osismi, is famous for its oracle of a Gaulish god, whose priestesses, living in the holiness of perpetual virginity, are said to be nine in number.

They call them Gallizenae, and they believe them to be endowed with extraordinary gifts to rouse the sea and the wind by their incantations, to turn themselves into whatsoever animal form they may choose, to cure diseases which among others are incurable, to know what is to come and to foretell it.

Archaeologist Stuart Piggott compared the attitude of the Classical authors toward the druids as being similar to the relationship that had existed in the 15th and 18th centuries between Europeans and the societies that they were just encountering in other parts of the world, such as the Americas and the South Sea Islands.

[66] Historian Nora Chadwick, in a categorization subsequently adopted by Piggott, divided the Classical accounts of the druids into two groups, distinguished by their approach to the subject as well as their chronological contexts.

She calls the first of these groups the "Posidonian" tradition after one of its primary exponents, Posidonious, and notes that it takes a largely critical attitude towards the Iron Age societies of Western Europe that emphasizes their "barbaric" qualities.

[69] The earliest record of the druids comes from two Greek texts of c. 300 BCE: a history of philosophy written by Sotion of Alexandria, and a study of magic widely attributed to Aristotle.

The earliest extant text that describes druids in detail is Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, book VI, written in the 50s or 40s BCE.

A general who was intent on conquering Gaul and Britain, Caesar described the druids as being concerned with "divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, private or public, and the interpretation of ritual questions".

They were concerned with "the stars and their movements, the size of the cosmos and the earth, the world of nature, and the power and might of the immortal gods", indicating they were involved with not only such common aspects of religion as theology and cosmology, but also astronomy.

[78] John Creighton has speculated that in Britain, the druidic social influence was already in decline by the mid-1st century BCE, in conflict with emergent new power structures embodied in paramount chieftains.

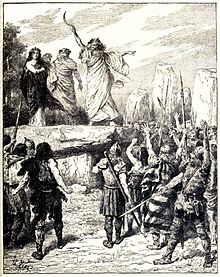

[41] Such an idea was expanded upon by Strabo, writing in the 20s CE, who declared that amongst the Gauls, there were three types of honoured figures:[82] The Roman writer Tacitus, who was himself a senator and historian, described how when the Roman army, led by Suetonius Paulinus, attacked the island of Mona (Anglesey; Welsh: Ynys Môn), the legionaries were awestruck on landing, by the appearance of a band of druids, who, with hands uplifted to the sky, poured forth terrible imprecations on the heads of the invaders.

[84] In the Middle Ages, after Ireland and Wales were Christianized, druids appear in a number of written sources, mainly tales and stories such as Táin Bó Cúailnge, and in the hagiographies of various saints.

The evidence of the law-texts, which were first written-down in the 600s and 700s CE, suggests that with the coming of Christianity, the role of the druid in Irish society was rapidly reduced to that of a sorcerer who could be consulted to cast spells or do healing magic, and that his standing declined accordingly.

Another law-text, Uraicecht Becc ('small primer'), gives the druid a place among the dóer-nemed, or professional classes, which depend upon a patron for their status, along with wrights, blacksmiths, and entertainers, as opposed to the fili, who alone enjoyed free nemed-status.

Minister Macauley (1764) reported the existence of five druidic altars, including a large circle of stones fixed perpendicularly in the ground near the Stallir House on Boreray near the westernmost settlement of the UK St, Kilda.

[101] Classics professor Phillip Freeman discusses a later reference to 'dryades', which he translates as 'druidesses', writing, "The fourth century CE collection of imperial biographies known as the Historia Augusta contains three short passages involving Gaulish women called 'dryades' ('druidesses').

Next, as they endeavoured, with every possible effort, to move forward, but were not able to take a step farther, they began to whirl themselves about in the most ridiculous fashion, until, not able any longer to sustain the weight, they set down the dead body."

Another Welshman, William Price (4 March 1800 – 23 January 1893), a physician known for his support of Welsh nationalism, Chartism, and his involvement with the Neo-Druidic religious movement, has been recognized as a significant figure of 19th century Wales.

In the 20th century, as new forms of textual criticism and archaeological methods were developed, allowing for greater accuracy in understanding the past, various historians and archaeologists published books on the subject of the druids, and came to their own conclusions.