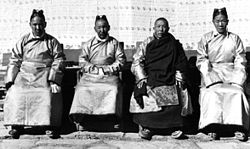

Tibetan dual system of government

Under the Cho-sid-nyi, both religious and temporal authorities wield actual political power, albeit within officially separate institutions.

Since at least the period of the Mongol presence in Tibet during the 13th and 14th centuries, Buddhist and Bön clerics had participated in secular government, having the same rights as laymen to be appointed state officials, both military and civil.

[1] By the Ming dynasty (founded 1368), the Sakya held office above the heads of both components, embodying a government of both chos and srid.

[1] The dual system was implemented during a period of consolidation under the Fifth Dalai Lama (r. 1642–1682), who unified Tibet religiously and politically after a prolonged civil war.

He brought the government of Tibet under the control of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism after defeating the rival Kagyu and Jonang sects and the secular ruler, the Tsangpa prince.

In Ladakh and Sikkim, two related Chogyal dynasties reigned with absolute control, punctuated by periods of invasion and colonization by Tibet, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and the British Empire.

The autonomy of the Tibetan élite in Ladakh, as well as their system of government, ended with the campaigns of General Zorawar Singh and Rajput suzerainty.

[8][9] In 1962, Jigme Ngawang Namgyal, known as Shabdrung Rimpoche to his followers, fled Bhutan for India where he spent the remainder of his life.

Furthermore, the Druk Gyalpo appoints the Je Khenpo on advice of the Five Lopons, and the democratic Constitution itself is the supreme law of the land, as opposed to a Shabdrung figurehead.

Aside from seats reserved for religious representatives, offices are generally open to clerics: the Prime Minister of its Parliament is Lobsang Tenzin, a Buddhist monk.

The administration of the government in exile was headed for decades by the Dalai Lama, but in 2011, he ceded his temporal (secular) powers, keeping only his role as spiritual leader.