Ductus venosus

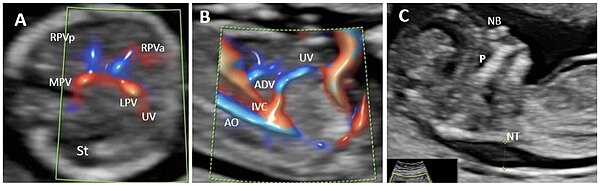

In the fetus, the ductus venosus ("DV"; Arantius' duct after Julius Caesar Aranzi[1]) shunts a portion of umbilical vein blood flow directly to the inferior vena cava.

Compared to the 50% shunting of umbilical blood through the ductus venosus found in animal experiments, the degree of shunting in the human fetus under physiological conditions is considerably less, 30% at 20 weeks, which decreases to 18% at 32 weeks, suggesting a higher priority of the fetal liver than previously realized.

[3] In conjunction with the other fetal shunts, the foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus, it plays a critical role in preferentially shunting oxygenated blood to the fetal brain.

This anatomic course is important to recall when assessing the success of neonatal umbilical venous catheterization, as failure to cannulate through the ductus venosus results in malpositioned hepatic catheterization via the left or right portal veins.

If the ductus venosus fails to occlude after birth, it remains patent (open), and the individual is said to have a patent ductus venosus and thus an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (PSS).

[5] Possibly, increased levels of dilating prostaglandins leads to a delayed occlusion of the vessel.