Dunstanburgh Castle

Thomas was a leader of a baronial faction opposed to King Edward II, and probably intended Dunstanburgh to act as a secure refuge, should the political situation in southern England deteriorate.

The castle was maintained in the 15th century by the Crown, and formed a strategic northern stronghold in the region during the Wars of the Roses, changing hands between the rival Lancastrian and Yorkist factions several times.

[1] As the Scottish border became more stable, the military utility of the castle steadily diminished, and King James I finally sold the property off into private ownership in 1604.

The Grey family owned it for several centuries; increasingly ruinous, it became a popular subject for artists, including Thomas Girtin and J. M. W. Turner, and formed the basis for a poem by Matthew Lewis in 1808.

The castle's ownership changed during the 19th and 20th centuries; by the 1920s its owner Sir Arthur Sutherland could no longer afford to maintain Dunstanburgh, and he placed it under the guardianship of the state in 1930.

The ruins are protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building and are part of a Site of Special Scientific Interest, forming an important natural environment for birds and amphibians.

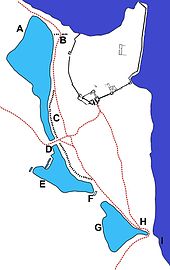

Dunstanburgh Castle was built in the centre of a designed medieval landscape, surrounded by three artificial lakes called meres covering a total of 4.25 hectares (10.5 acres).

[10] In the years following Gaveston's death, however, civil conflict in England rarely seemed far away, and it is currently believed that Thomas probably intended to create a secure retreat, a safe distance away from Edward's forces in the south.

Northumbria was a lawless region in this period, suffering from the activities of thieves and schavaldours, a type of border brigand, many of whom were members of Edward II's household, and the harbour may have represented a safer way to reach the castle than land routes.

[24] By 1326, the castle was given back to Thomas's brother, Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, with Lilburn returning as its constable, and continued to be of use in defence against the Scottish invasions over the next few decades.

[27] The surrounding manor of Embleton had nonetheless suffered from Scottish raids and Gaunt had concerns over the condition of the castle's defences, ordering the building of additional fortifications around the gatehouse.

[30] He found himself stranded in the north of England in the early part of the revolt but considered Dunstanburgh insufficiently secure to function as a safe haven, and was forced to turn to Alnwick Castle instead, which refused to let him in, fearing that his presence would invite a rebel attack.

[31] A wide range of work was carried out under the direction of the constable, Thomas of Ilderton, and the mason Henry of Holme, including blocking up the entrance in the gatehouse to turn it into a keep.

[37] The castle formed part of a sequence of fortifications protecting the eastern route into Scotland, and in 1461 King Edward IV attempted to break the Lancastrian stranglehold on the region.

[13] In 1462, Henry VI's wife, Margaret of Anjou, invaded England with a French army, landing at Bamburgh; Percy then switched sides and declared himself for the Lancastrians.

[39] Percy was left in charge of Dunstanburgh as part of Edward IV's attempts at reconciliation, but the next year he once again switched sides, returning the castle to the Lancastrians.

[54] The historian Cadwallader John Bates undertook fieldwork at the castle in the 1880s, publishing a comprehensive work in 1891, and a professional architectural plan of the ruins was produced in 1893.

[49] Thomas Girtin toured the region and painted the castle, his picture dominated by what art historian Souren Melikian describes as "the forces of nature unleashed", with "wild waves" and dark clouds swirling around the ruins.

[59] A similarly wild view was painted by Thomas Allom showing a ship in a heavy sea offshore, the wreck of which is taken up by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in her poetical illustration to an engraving of that work Dunstanburgh Castle.

[68] The castle itself was occupied by a unit of the Royal Armoured Corps, who served as observers; the soldiers appear to have relied on the stone walls for protection rather than trenches, and, unusually, no additional firing points were cut out of the stonework, as typically happened elsewhere.

[69] The surrounding beaches were defended with lines of barbed wire, slit trenches and square weapons pits, reinforced by concrete pillboxes to the north and south of the castle, at least partially laid down by the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment.

[91] A protective earthen bank, probably originally reinforced by a timber palisade, ran for approximately 490 feet (150 m) along either side of the West Gate, where a gatehouse was probably built.

[107] This was heavily influenced by the Edwardian gatehouses in North Wales, such as that at Harlech, but contains unique features, such as the frontal towers, and is considered by historians Alastair Oswald and Jeremy Ashbee to be "one of the most imposing structures in any English castle".

[98] Early analysis of Dunstanburgh Castle focused on its qualities as a military, and a defensive site, but more recent work has emphasised the symbolic aspects of its design and the surrounding landscape.

[127] Although the castle was intended as a secure bolt-hole for Thomas of Lancaster should events go awry in the south of England, it was, however "clearly not an inconspicuous hiding place", as the English Heritage research team have pointed out: it was a spectacular construction, located in the centre of a huge, carefully designed medieval landscape.

[131] The Lilburn Tower was positioned to be clearly – and provocatively – visible to Edward II's castle at Bamburgh, 9 miles (14 km) away along the coast, and would have been elegantly framed by the entranceway to the Great Gatehouse for any visitors.

[135] Dunstanburgh, with an ancient fort at its centre encircled by water, may have been an allusion to Camelot, and in turn to Thomas's claim to political authority over the failing Edward II, and was also strikingly similar to contemporary depictions of Sir Lancelot's castle of "Joyous Garde".

[137] Different versions of the story vary slightly in their details, but typically involve a knight, Sir Guy, arriving at Dunstanburgh Castle, where he was met by a wizard and led inside.

[140] Another centres on a man called Gallon who was left in charge of the castle by Margaret of Anjou and entrusted with a set of valuables; captured by the Yorkists, he escaped and later returned to reclaim six Venetian glasses.

[140] The historian Katrina Porteous has noted that in the 14th century there are records of receivers and bailiffs at the castle called Galoun, potentially linked to the origins of the Gallon of this story.

Sir Guy the Seeker