EC Comics

Noted for their high quality and shock endings,[2] these stories were also unique in their socially conscious, progressive themes (including racial equality, anti-war advocacy, nuclear disarmament, and environmentalism) that anticipated the Civil Rights Movement and the dawn of the 1960s counterculture.

[3] In 1954–55, censorship pressures prompted it to concentrate on the humor magazine Mad, leading to the company's greatest and most enduring success.

After four years (1942–1946) in the Army Air Corps, Gaines had returned home to finish school at New York University, planning to work as a chemistry teacher.

His editors, Al Feldstein and Harvey Kurtzman, who also drew covers and stories, gave assignments to such prominent and highly accomplished freelance artists as Johnny Craig, Reed Crandall, Jack Davis, Will Elder, George Evans, Frank Frazetta, Graham Ingels, Jack Kamen, Bernard Krigstein, Joe Orlando, John Severin, Al Williamson, Basil Wolverton, and Wally Wood.

These titles reveled in a gruesome joie de vivre, with grimly ironic fates meted out to many of the stories' protagonists.

The company's war comics, Frontline Combat and Two-Fisted Tales, often featured weary-eyed, unheroic stories out of step with the jingoistic times.

Shock SuspenStories tackled weighty political and social issues such as racism, sex, drug use, and the American way of life.

As noted by Max Allan Collins in his story annotations for Russ Cochran's 1983 hardcover reprint of Crime SuspenStories, Johnny Craig had developed a "film noir-ish bag of effects" in his visuals,[page needed] while characters and themes found in the crime stories often showed the strong influence of writers associated with film noir, notably James M.

[citation needed] Craig excelled in drawing stories of domestic scheming and conflict, leading David Hajdu to observe: To young people of the postwar years, when the mainstream culture glorified suburban domesticity as the modern American ideal – the life that made the Cold War worth fighting – nothing else in the panels of EC comics, not the giant alien cockroach that ate earthlings, not the baseball game played with human body parts, was so subversive as the idea that the exits of the Long Island Expressway emptied onto levels of Hell.

Gaines would generally stay up late and read large amounts of material while seeking "springboards" for story concepts.

Besides gleefully recounting the unpleasant details of the stories, the characters squabbled with one another, unleashed an arsenal of puns, and even insulted and taunted the readers: "Greetings, boils and ghouls..." This irreverent mockery of the audience also became the trademark attitude of Mad, and such glib give-and-take was later mimicked by many, including Stan Lee at Marvel Comics.

[citation needed] EC's most enduring legacy came with Mad, which started as a side project for Kurtzman before buoying the company's fortunes and becoming one of the country's most notable and long-running humor publications.

[15] Gaines switched focus to EC's Picto-Fiction titles, a line of typeset black-and-white magazines with heavily illustrated stories.

Fiction was formatted to alternate illustrations with blocks of typeset text, and some of the contents were rewrites of stories previously published in EC's comic books.

EC's Ray Bradbury adaptations were collected in The Autumn People (horror and crime) and Tomorrow Midnight (science fiction).

In addition to the stories from EC's horror titles, the book also included Bernard Krigstein's famous "Master Race" story from Impact and the first publication of Angelo Torres' "An Eye for an Eye", originally slated for the final issue of Incredible Science Fiction but rejected by the Comics Code.

[citation needed] In February 2010, IDW Publishing began publishing a series of Artist's Editions books in 15" × 22" format, which consist of scans of the original inked comic book art, including pasted lettering and other editorial artifacts that remain on the original pages.

The problem came to a head in 1948 with the publication by Dr. Fredric Wertham of two articles: "Horror in the Nursery" (in Collier's) and "The Psychopathology of Comic Books" (in the American Journal of Psychotherapy).

As a result, an industry trade group, the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, was formed in 1948 but proved ineffective.

At the same time, a federal investigation led to a shakeup in the distribution companies that delivered comic books and pulp magazines across America.

When distributors refused to handle many of his comics, Gaines ended publication of his three horror and the two SuspenStory titles on September 14, 1954.

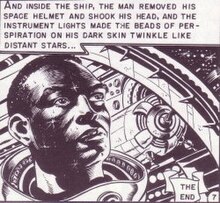

[37] The story, by the writer Al Feldstein and artist Joe Orlando, was a reprint from the pre-Code Weird Fantasy #18 (April 1953), inserted when the Code Authority had rejected an initial, original story, "An Eye for an Eye", drawn by Angelo Torres, but was itself also "objected to" because of "the central character being Black".

[38] The story depicted a human astronaut, a representative of the Galactic Republic, visiting the planet Cybrinia, inhabited by robots.

He finds the robots divided into functionally identical orange and blue races, with one having fewer rights and privileges than the other.

The astronaut determines that due to the robots' bigotry, the Galactic Republic should not admit the planet until these problems are resolved.

[citation needed] As Diehl recounted in Tales from the Crypt: The Official Archives: This really made 'em go bananas in the Code czar's office.

[Feldstein] reported the results of his audience with the czar to Gaines, who was furious [and] immediately picked up the phone and called Murphy.

[15]Feldstein, interviewed for the book Tales of Terror: The EC Companion, reiterated his recollection of Murphy making the request: So he said it can't be a Black [person].