European Union competition law

To avoid different interpretations of EC Competition Law, which could vary from one national court to the next, the commission was made to assume the role of central enforcement authority.

Yet some analysts assert that the commission's monopoly policy (the enforcement of Art 102) has been "largely ineffective",[5] because of the resistance of individual Member State governments that sought to shield their most salient national companies from legal challenges.

For instance, Valentine Korah, an eminent legal analyst in the field, argued that the commission was too strict in its application of EC Competition rules and often ignored the dynamics of company behaviour, which, in her opinion, could actually be beneficial to consumers and to the quality of available goods in some cases.

Nonetheless, the arrangements in place worked fairly well until the mid-1980s, when it became clear that with the passage of time, as the European economy steadily grew in size and anti-competitive activities and market practices became more complex in nature, the commission would eventually be unable to deal with its workload.

In its 2005 report,[specify] the OECD lauded the modernisation effort as promising, and noted that decentralisation helps to redirect resources so the DG Competition can concentrate on complex, Community-wide investigations.

For instance, on 20 December 2006, the Commission publicly backed down from 'unbundling' French (EdF) and German (E.ON) energy giants, facing tough opposition from Member State governments.

Another legal battle is currently ongoing over the E.ON-Endesa merger, where the commission has been trying to enforce the free movement of capital, while Spain firmly protects its perceived national interests.

[9] However, when there are such differences in many Member States' policy preferences and given the benefits of experimentation, in 2020 one might ask whether more diversity (within limits) might not produce a more efficient, effective and legitimate competition regime.

[13] This means that trade unions cannot be regarded as subject to competition law, because their central objective is to remedy the inequality of bargaining power that exists in dealing with employers who are generally organised in a corporate form.

[17] Under the original EUMR, according to Article 2(3), for a merger to be declared compatible with the common market, it must not create or strengthen a dominant position where it could affect competition,[18] thus the central provision under EU law ask whether a concentration would if it went ahead would "significantly impede effective competition…".

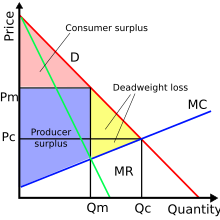

[55] The Commission provides examples of normal, positive, competitive behavior as offering lower prices, better quality products and a wider choice of new and improved goods and services.

[56] From this, it can be inferred that behavior that is abnormal – or not 'on the merits' – and therefore amounting to abuse, includes such infractions as margin squeezing, refusals to supply and the misleading of patent authorities.

[67][68] In order for behaviour to be objectively justifiable, the conduct in question must be proportionate[69] and would have to be based on factors external to the dominant undertaking's control,[70] such as health or safety considerations.

Any "undertaking" is regulated, and this concept embraces de facto economic units, or enterprises, regardless of whether they are a single corporation, or a group of multiple companies linked through ownership or contract.

Covered therefore is a whole range of behaviour from a strong handshaken, written or verbal agreement to a supplier sending invoices with directions not to export to its retailer who gives "tacit acquiescence" to the conduct.

However, a coincidental increase in prices will not in itself prove a concerted practice, there must also be evidence that the parties involved were aware that their behaviour may prejudice the normal operation of the competition within the common market.

The Council Regulation n. 139/2004[82] established antitrust national authorities of EU member States have the competence to judge on undertakings whose economic and financial impact are limited to their respective internal market.

The Commission guideline on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 23 (2) (a) of Regulation 1/2003[87] uses a two-step methodology: The basic amount relates, inter alia, to the proportion of the value of the sales depending on the degree of the gravity of the infringement.

In the latter case, immunity from fines may be granted to the company who submits evidence first to the European Commission which enables it to carry out an investigation and/or to find an infringement of Article 101 TFEU.

However, when there are such differences in many Member States' policy preferences and given the benefits of experimentation, in 2020 one might ask whether more diversity (within limits) might not produce a more efficient, effective and legitimate competition regime.

The structure of the economy, inherited from the central planning system, was characterised with a high level of monopolisation, which could significantly limit the success of the economic transformation.

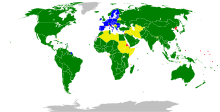

Romania has moved up in the rankings of the Global Competition Review since 2017 and won 3 stars, along with seven other EU countries (Austria, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Sweden).

According to Global Trend Monitor 2018 (published on PaRR-global.com), Romania is one of the most competitive jurisdictions between countries in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, ranked 10th in this top (after moving up 4 positions compared to the previous year).

[107] The Big Data platform would give the Authority significant resources with regards to (i) bid rigging cases; (ii) cartel screening; (iii) Structural and commercial connections between undertakings; (iv) sectorial inquiries; (v) mergers.

Chapter 5 of the post war Havana Charter contained an Antitrust code[108] but this was never incorporated into the WTO's forerunner, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1947.

Office of Fair Trading Director and Professor Richard Whish wrote sceptically that it "seems unlikely at the current stage of its development that the WTO will metamorphose into a global competition authority.

This affirms, "the place occupied by services of general economic interest in the shared values of the Union as well as their role in promoting social and territorial cohesion."

GB argued that the special rights enjoyed by RTT under Belgian law infringed Article 86, and the case went to the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

France's former president Nicolas Sarkozy has called for the reference in the preamble to the Treaty of the European Union to the goal of "free and undistorted competition" to be removed.

Deutsche Post was accused of predatory pricing in the business parcel delivery sector (i.e. not one of the services "reserved" under the directive) by the private firm UPS.