Eadred

Edmund and Eadred both inherited kingship of the whole kingdom, lost it shortly afterwards when York accepted Viking kings, and recovered it by the end of their reigns.

In 954, the York magnates expelled their last king, Erik Bloodaxe, and Eadred appointed Osullf, the Anglo-Saxon ruler of the north Northumbrian territory of Bamburgh, as the first ealdorman of the whole of Northumbria.

Eadred had been very close to Edmund and inherited many of his leading advisers, such as his mother Eadgifu, Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Æthelstan, ealdorman of East Anglia, who was so powerful that he was known as the "Half-King".

However, like earlier kings he did not share the view of the circle around Æthelwold that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile religious life and he appointed Ælfsige, a married man with a son, as Bishop of Winchester.

By 878, they had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex, but in that year the West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington.

While they were marching back to Northumbria, they were caught by an Anglo-Saxon army and decisively defeated at the Battle of Tettenhall, ending the threat from the Northumbrian Vikings for a generation.

In the 910s, Edward and Æthelflæd – his sister and Æthelred's widow – extended Alfred's network of fortresses and conquered Viking-ruled eastern Mercia and East Anglia.

On 26 May 946, he was stabbed to death trying to protect his seneschal from attack by a convicted outlaw at Pucklechurch in Gloucestershire, and as his sons were young children Eadred became king.

According to the twelfth century chronicler William of Malmesbury, Edmund was about eighteen years old when he succeeded to the throne in 939, which dates his birth to 920–921, and their father Edward died in 924, so Eadred was born around 923.

According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan showed great affection towards Edmund and Eadred: "mere infants at his father's death, he brought them up lovingly in childhood, and when they grew up gave them a share in his kingdom".

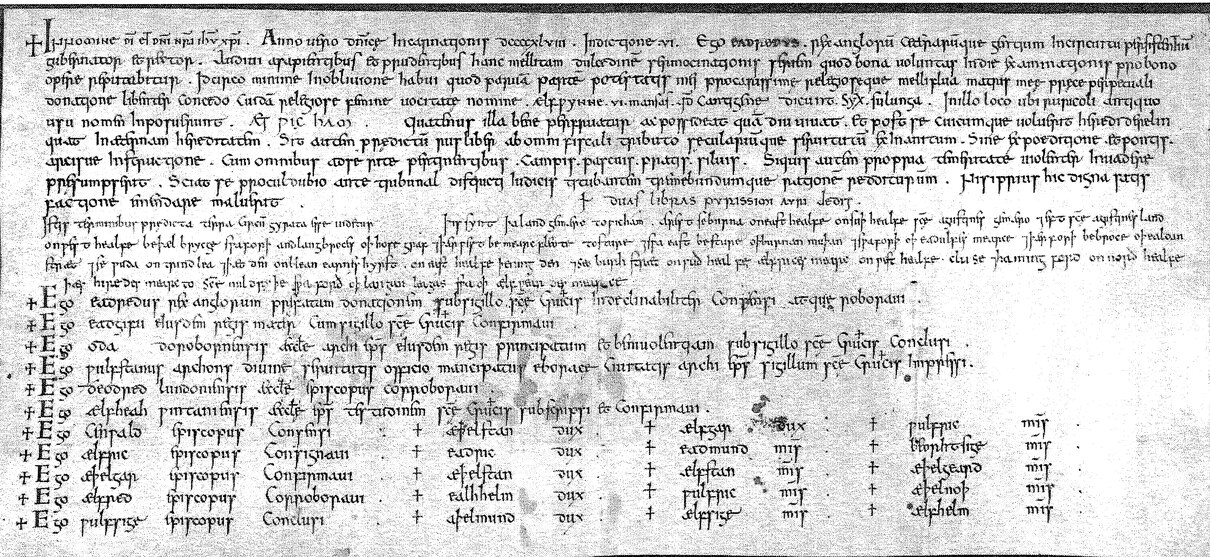

[8] At a royal assembly shortly before Æthelstan's death in 939, Edmund and Eadred attested charter S 446,[a] which granted land to their full sister, Eadburh.

Eadgifu attested around one-third of Edmund's charters, always as regis mater (king's mother), including all grants to religious institutions and individuals.

[19] He was crowned by Archbishop Oda of Canterbury on 16 August 946 at Kingston upon Thames, attended by Hywel Dda, king of Deheubarth in south Wales, Wulfstan and Osulf.

[23] Erik was assassinated shortly afterwards, possibly at the instigation of Osulf, and the historian Frank Stenton comments that the time was past when an individual adventurer could establish a dynasty in England.

[31] In his will, Eadred left 1600 pounds[e] to be used for protection of his people from famine or to buy peace from a heathen army, showing that he did not regard England as safe from attack.

[44] Force was fundamental to West Saxon kings' domination of England, and the historian George Molyneaux sees the Thetford slaughter as an example of their "intermittently unleashed crude but terrifying displays of coercive power".

A charter issued at Easter 949 describes Eadred as "exalted with royal crowns",[51] displaying the king as an exceptional and charismatic character set apart from other men.

The reason for the dramatic change in around 950 is not known, but may be due to Eadred transferring responsibility for charter production from the royal writing office to other centres when his health declined in his last years.

[56] One alternative tradition is found in the "alliterative charters", produced between 940 and 956, which display frequent use of alliteration and unusual vocabulary, in a style influenced by Aldhelm, the seventh century bishop of Sherborne.

[60] They were produced between 951 and 986,[61] but they appear to be foreshadowed by a charter of 949 granting Reculver minster and its lands to Christ Church, Canterbury, which claims to be written by Dunstan "with his own fingers".

[65] Several "alliterative" charters, including one issued on the occasion of Eadred's coronation, use expressions such as "the government of kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons and Northumbrians, of the pagans and the Britons".

[76] The major religious movement of the tenth century, the English Benedictine Reform, reached its peak under Edgar, but Eadred was a strong supporter in its early stages.

[79] The historian Nicholas Brooks comments: "The evidence is indirect and inadequate but may suggest that Dunstan drew much of his support from the regiment of powerful women in early tenth-century Wessex and from Eadgifu in particular."

[80] During Eadred's reign, Æthelwold asked for permission to go abroad to gain a deeper understanding of the scriptures and a monk's religious life, no doubt at a reformed monastery such as Fleury.

[5] Eadred refused his mother's advice that he should not allow such a wise man to leave his kingdom, instead appointing him as abbot of Abingdon, which was then served by secular priests and which Æthelwold transformed into a leading Benedictine abbey.

[85] Wilfrid had been an assertively independent northern bishop and in the historian David Rollason's view the theft may have been intended to prevent the relics from becoming a focus for opposition to the West Saxon dynasty.

[92] In 953, Eadred granted land in Sussex to his mother, and she is described in the charter as famula Dei, which probably means that she adopted a religious life while retaining her own estates, and did not enter a monastery.

[114] Northumbria fought for its independence against successive West Saxon kings, but the acceptance of Erik proved to be its last throw and it was finally conquered during Eadred's reign.

In the view of the historian Ben Snook, Eadred "relied on a kitchen cabinet to run the country on his behalf and seems never to have exercised much direct authority.

[118] When he acceded, Eadwig dispossessed Eadgifu and exiled Dunstan, apparently as part of an attempt to free himself from the powerful advisers of his father and uncle.