France in the early modern period

The period is dominated by the figure of the "Sun King", Louis XIV (his reign of 1643–1715 being one of the longest in history), who managed to eliminate the remnants of medieval feudalism and established a centralized state under an absolute monarch, a system that would endure until the French Revolution and beyond.

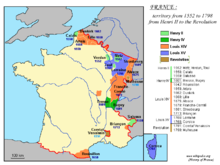

In the mid 15th century, France was significantly smaller than it is today,[a] and numerous border provinces (such as Roussillon, Cerdagne, Calais, Béarn, Navarre, County of Foix, Flanders, Artois, Lorraine, Alsace, Trois-Évêchés, Franche-Comté, Savoy, Bresse, Bugey, Gex, Nice, Provence, Corsica and Brittany) were autonomous or foreign-held (as by the Kingdom of England); there were also foreign enclaves, like the Comtat Venaissin.

During this period, France expanded to nearly its modern territorial extent through the acquisition of Picardy, Burgundy, Anjou, Maine, Provence, Brittany, Franche-Comté, French Flanders, Navarre, Roussillon, the Duchy of Lorraine, Alsace and Corsica.

Although Paris was the capital of France, the later Valois kings largely abandoned the city as their primary residence, preferring instead various châteaux of the Loire Valley and Parisian countryside.

The southern half of the country continued to speak Occitan languages (such as Provençal), and other inhabitants spoke Breton, Catalan, Basque, Dutch (West Flemish), and Franco-Provençal.

In 1492 and 1493, after supporting the victorious House of Tudor in the Battle of Bosworth Field, Charles VIII of France signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England, Maximilian I of Habsburg, and Ferdinand II of Aragon respectively at Étaples (1492), Senlis (1493) and in Barcelona (1493).

Charles VIII marched into Italy with a core force consisting of noble horsemen and non-noble foot soldiers, but in time the role of the latter grew stronger so that by the middle of the 16th century, France had a standing army of 5000 cavalry and 30,000 infantry.

[7] Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, seeking an ally against the Republic of Venice, encouraged Charles VIII of France to invade Italy, using the Angevin claim to the throne of Naples, then under Aragonese control, as a pretext.

Ludovico, having betrayed the French at Fornovo, retained his throne until 1499, when Charles's successor, Louis XII of France, invaded Lombardy and seized Milan.

The Holy League, left victorious, fell apart over the subject of dividing the spoils, and in 1513 Venice allied with France, agreeing to partition Lombardy between them.

A lack of cooperation between the Spanish and English armies, coupled with increasingly aggressive Ottoman attacks, led Charles to abandon these conquests, restoring the status quo once again.

In 1547, Henry II of France, who had succeeded Francis to the throne, declared war against Charles with the intent of recapturing Italy and ensuring French, rather than Habsburg, domination of European affairs.

A growing urban-based Protestant minority (later dubbed Huguenots) faced ever harsher repression under the rule of Francis I's son King Henry II.

[11] Henry IV's son Louis XIII and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu, elaborated a policy against Spain and the German emperor during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) which had broken out among the lands of Germany's Holy Roman Empire.

An English-backed Huguenot rebellion (1625–1628) defeated, France intervened directly (1635) in the wider European conflict following her ally (Protestant) Sweden's failure to build upon initial success.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.

For most of the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715), France was the dominant power in Europe, aided by the diplomacy of Richelieu's successor (1642–1661) Cardinal Mazarin and the economic policies (1661–1683) of Colbert.

The resistance of peasants to adopt the potato, according to some monarchist apologists, and other new agricultural innovations while continuing to rely on cereal crops led to repeated catastrophic famines long after they had ceased in the rest of Western Europe.

With the Palais du Luxembourg, the Château de Maisons and Vaux-le-Vicomte, French classical architecture was admired abroad even before the creation of Versailles or Perrault's Louvre colonnade.

In an effort to prevent the nobility from revolting and challenging his authority, Louis implemented an extremely elaborate system of court etiquette with the idea that learning it would occupy most of the nobles' time and they could not plan rebellion.

Also, Louis willingly granted titles of nobility to those who had performed distinguished service to the state so that it did not become a closed caste and it was possible for commoners to rise through the social ranks.

Starting in the 1670s, Louis XIV established the so-called Chambers of Reunion, courts in which judges would determine whether certain Habsburg territories belonged rightfully to France.

The reign (1715–1774) of Louis XV saw an initial return to peace and prosperity under the regency (1715–1723) of Philip II, Duke of Orléans, whose policies were largely continued (1726–1743) by Cardinal Fleury, prime minister in all but name.

But alliance with the traditional Habsburg enemy (the "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756) against the rising power of Britain and Prussia led to costly failure in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) and the loss of France's North American colonies.

While less liberal than England during the same period, the French monarchy never approached the absolutism of the eastern rulers in Vienna, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Constantinople in part because the country's traditional development as a decentralized, feudal society acted as a restraint on the power of the king.

On the eve of the French Revolution of 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.

[18] Within early modern society, women of urban artisanal classes participated in a range of public activities and also shared work settings with men (even though they were generally disadvantaged in terms of tasks, wages and access to property.

The sons and daughters of the noble and bourgeois elites, however, were given quite distinct educations: boys were sent to upper school, perhaps a university, while their sisters (if they were lucky enough to leave the house) were sent for finishing at a convent.

[22] By a policy adopted at the beginning of the 16th century, adulterous women during the ancien régime were sentenced to a lifetime in a convent unless pardoned by their husbands and were rarely allowed to remarry even if widowed.

The ensuring French Wars of Religion, and particularly the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, decimated the Huguenot community;[26][27] Protestants declined to seven to eight percent of the kingdom's population by the end of the 16th century.

Last King of Early France. By Joseph Duplessis (1775) .