Earth's rotation

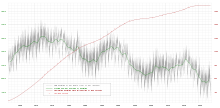

Atomic clocks show that the modern day is longer by about 1.7 milliseconds than a century ago,[1] slowly increasing the rate at which UTC is adjusted by leap seconds.

[4] This increase in speed is thought to be due to various factors, including the complex motion of its molten core, oceans, and atmosphere, the effect of celestial bodies such as the Moon, and possibly climate change, which is causing the ice at Earth's poles to melt.

Conservation of angular momentum dictates that a mass distributed more closely around its centre of gravity spins faster.

[7] This was accepted by most of those who came after, in particular Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century CE), who thought Earth would be devastated by gales if it rotated.

[11] According to al-Biruni, al-Sijzi (d. c. 1020) invented an astrolabe called al-zūraqī based on the idea believed by some of his contemporaries "that the motion we see is due to the Earth's movement and not to that of the sky.

[15] In medieval Europe, Thomas Aquinas accepted Aristotle's view[16] and so, reluctantly, did John Buridan[17] and Nicole Oresme[18] in the fourteenth century.

Not until Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543 adopted a heliocentric world system did the contemporary understanding of Earth's rotation begin to be established.

[19] Tycho Brahe, who produced accurate observations on which Kepler based his laws of planetary motion, used Copernicus's work as the basis of a system assuming a stationary Earth.

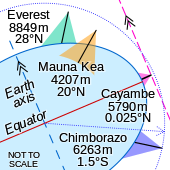

However, measurements by Maupertuis and the French Geodesic Mission in the 1730s established the oblateness of Earth, thus confirming the positions of both Newton and Copernicus.

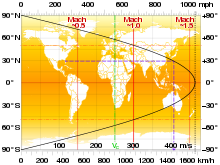

The Coriolis effect is mainly observable at a meteorological scale, where it is responsible for the opposite directions of cyclone rotation in the Northern and Southern hemispheres (anticlockwise and clockwise, respectively).

Hooke, following a suggestion from Newton in 1679, tried unsuccessfully to verify the predicted eastward deviation of a body dropped from a height of 8.2 meters, but definitive results were obtained later, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, by Giovanni Battista Guglielmini in Bologna, Johann Friedrich Benzenberg in Hamburg and Ferdinand Reich in Freiberg, using taller towers and carefully released weights.

[29][30][31] Random fluctuations due to core-mantle coupling have an amplitude of about 5 ms.[32][33] The mean solar second between 1750 and 1892 was chosen in 1895 by Simon Newcomb as the independent unit of time in his Tables of the Sun.

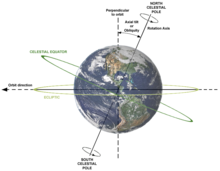

Earth's rotation period relative to the International Celestial Reference Frame, called its stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), is 86 164.098 903 691 seconds of mean solar time (UT1) (23h 56m 4.098903691s, 0.99726966323716 mean solar days).

This is a result of the Earth turning 1 additional rotation, relative to the celestial reference frame, as it orbits the Sun (so 366.24 rotations/y).

[35][n 4] Multiplying by (180°/π radians) × (86,400 seconds/day) yields 360.9856 °/day, indicating that Earth rotates more than 360 degrees relative to the fixed stars in one solar day.

[43] Earth's rotation axis moves with respect to the fixed stars (inertial space); the components of this motion are precession and nutation.

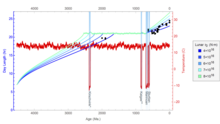

Over millions of years, Earth's rotation has been slowed significantly by tidal acceleration through gravitational interactions with the Moon.

This process has gradually increased the length of the day to its current value, and resulted in the Moon being tidally locked with Earth.

[46] The current rate of tidal deceleration is anomalously high, implying Earth's rotational velocity must have decreased more slowly in the past.

[47] Some recent large-scale events, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, have caused the length of a day to shorten by 3 microseconds by reducing Earth's moment of inertia.

For example, NASA scientists calculated that the water stored in the Three Gorges Dam has increased the length of Earth's day by 0.06 microseconds due to the shift in mass.

[53] There are recorded observations of solar and lunar eclipses by Babylonian and Chinese astronomers beginning in the 8th century BCE, as well as from the medieval Islamic world[54] and elsewhere.

These observations can be used to determine changes in Earth's rotation over the last 27 centuries, since the length of the day is a critical parameter in the calculation of the place and time of eclipses.

This primordial cloud was composed of hydrogen and helium produced in the Big Bang, as well as heavier elements ejected by supernovas.

As this interstellar dust is heterogeneous, any asymmetry during gravitational accretion resulted in the angular momentum of the eventual planet.

[58] However, if the giant-impact hypothesis for the origin of the Moon is correct, this primordial rotation rate would have been reset by the Theia impact 4.5 billion years ago.