Ecological efficiency

It is determined by a combination of efficiencies relating to organismic resource acquisition and assimilation in an ecosystem.

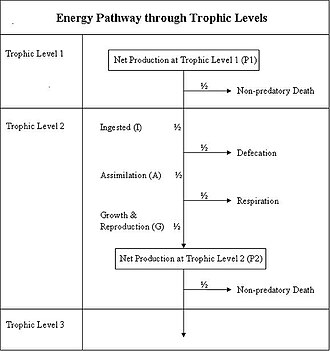

Due to non-predatory death, egestion, and cellular respiration, a significant amount of energy is lost to the environment instead of being absorbed for production by consumers.

The loss of energy by a factor of one half from each of the steps of non-predatory death, defecation, and respiration is typical of many living systems.

Finally one half of the remaining energy is lost through respiration while the rest (63 units) is used for growth and reproduction.

This energy expended for growth and reproduction constitutes to the net production of trophic level 1, which is equal to

Assessing ingestion, for example, requires knowledge of the gross amount of food consumed in an ecosystem as well as its caloric content.

On the other hand, an approximation may be enough for most ecosystems, where it is important not to get an exact measure of efficiency, but rather a general idea of how energy is moving through its trophic levels.

In agricultural environments, maximizing energy transfer from producer (food) to consumer (livestock) can yield economic benefits.

A sub-field of agricultural science has emerged that explores methods of monitoring and improving ecological and related efficiencies.

While it is possible to improve the efficiency of energy use by livestock, it is vital to the world food question to also consider the differences between animal husbandry and plant agriculture.

The rest of the energy input into cultivating feed is respired or egested by the livestock and unable to be used by humans.

In comparing the cultivation of animals versus plants, there is a clear difference in magnitude of energy efficiency.

When organisms are consumed, approximately 10% of the energy in the food is fixed into their flesh and is available for next trophic level (carnivores or omnivores).

When a carnivore or an omnivore in turn consumes that animal, only about 10% of energy is fixed in its flesh for the higher level.

Furthermore, the ten percent law shows the inefficiency of energy capture at each successive trophic level.