Economic history of India

[3] The resulting political unity and military security allowed for a common economic system and enhanced trade and commerce, with increased agricultural productivity.

[citation needed] The Maurya Empire was followed by classical and early medieval kingdoms, including the Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras, Guptas, Western Gangas, Harsha, Palas, Rashtrakutas and Hoysalas.

[10] The Maratha Empire also managed an effective administration and tax collection policy throughout the core areas under its control and extracted chauth from vassal states.

The Republic of India, founded in 1947, adopted central planning for most of its independent history, with extensive public ownership, regulation, red tape and trade barriers.

[17] Evidence of well-laid streets, drainage systems and water supply in the valley's major cities, Dholavira, Harappa, Lothal, Mohenjo-daro and Rakhigarhi, reveals their knowledge of urban planning.

[21] Along with the family- and individually-owned businesses, ancient India possessed other forms of engaging in collective activity, including the gana, pani, puga, vrata, sangha, nigama and Shreni.

Historians Tapan Raychaudhuri and Irfan Habib claim this state patronage for overseas trade came to an end by the 13th century AD, when it was largely taken over by the local Parsi, Jewish, Syrian Christian and Muslim communities, initially on the Malabar and subsequently on the Coromandel coast.

[34][35][36][37] Further north, the Saurashtra and Bengal coasts played an important role in maritime trade, and the Gangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce.

[citation needed] From the 13th century onwards, India began adopting some mechanical technologies from the Islamic world, including gears and pulleys, machines with cams and cranks.

[73] Demand for European goods in Mughal India was lighter, Europe's exports being largely limited to some woolens, ingots, glassware, mechanical clocks, weapons, particularly blades for Firangi swords, and a few luxury items.

[74] The trade imbalance caused Europeans to export large quantities of silver and to a lesser extent gold to Mughal India to pay for South Asian imports.

[73] Bengali silk, cotton textiles, and cowrie shells were exported in large quantities to Europe, Indonesia, Japan,[77] and Africa, where they formed a significant element in the exchange of goods for slaves,[78] and treasure.

[90] Prasannan Parthasarathi countered that several post-Mughal states did not decline, notably Bengal, Marathas and Mysore, which were comparable to Britain into the late 18th century.

Immediately following the East India Company gaining the right to collect revenue, on behalf of the Nawab of Bengal, the Company largely ceased a century and a half practice of importing gold and silver, and for more than a decade, which it had hitherto used to pay for the goods shipped back to Britain, the American colonies, East Asia, or on to African Slavers, to be bartered for Slaves in the Atlantic Slave trade:[79] In addition, as under Mughal rule, land and opium revenue collected in the Bengal Presidency helped finance the company's administration, raise Sepoy armies, and fund wars in other parts of India, and later further afield, for example the Opium Wars, with additional capital raised, at typically 10%, from Banias money lenders.

[94] The abolition of the Atlantic slave trade, from 1807, both eliminated a significant export market,[79] and encouraged Caribbean plantations to organize the import of South Asian labor.

[98] The middlemen often failed to deliver the ordered quantity, or quality, to the contracted party, with pieces purchased with one companies money, from local weavers across the region, instead sold to a higher bidder.

[98] As they did they after the British East India Company started dictating the price of yarn sold within the region, which had historically accounted for the majority of the cost of a cotton piece.

[98] From the late 18th century British industry began to lobby their government to reintroduce the Calico Acts, and again start taxing Indian textile imports, while in parallel allow them access to the markets of India.

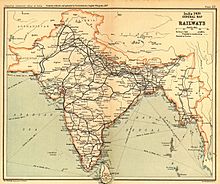

During the British Raj, massive railway projects were begun in earnest and government jobs and guaranteed pensions attracted a large number of upper caste Hindus into the civil service for the first time.

The issue was first raised by Edmund Burke who in the 1780s vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society, and elaborated on in the 19th century by Romesh Chunder Dutt.

Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.Economic historians have investigated regional differences in taxation, and public good provision, across the British Raj, with a strong positive correlation found between education spending, and Literacy in India; with historic Provincial policies still impacting comparative economic development, productivity, and employment.

[136] Other economic historians debate the impact of Mahatma Gandhi's establishment of the Swadeshi movement, and All India Village Industries Association, in the 1930s, to promote an alternative, self sufficient, indigenous, village economy, approach to development, over the Classical Western economic model; along with the impact of the Nonviolent resistance movement, with the mass boycottIng of industrial goods, tax strikes, and abolition of the salt tax, on public revenues, public programs, growth and industrialisation, in the last quarter of the British Raj.

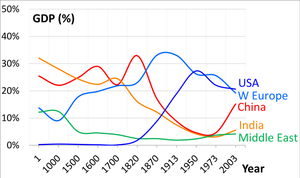

[58] Stephen Broadberry, Johann Custodis, and Bishnupriya Gupta, in 2014, offered the following comparative estimates for: Several economic historians claimed that in the 18th century real wages were falling in India, and were "far below European levels".

Between 1750 and 1810, they suggest the loss of Mughal hegemony allowed new despotic rulers to revenue farm their conquered populations, seeing tax and rent demands increase to 50% of production, compared to the 5–6% extracted in China during the period, and levied largely to fund regional warfare.

Angus Maddison states:[143] This was a shattering blow to manufacturers of fine muslins, jewellery, luxury clothing and footwear, decorative swords and weapons.

Extensive irrigation systems were built, providing an impetus for growing cash crops for export and for raw materials for Indian industry, especially jute, cotton, sugarcane, coffee, rubber, and tea.

[citation needed] With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to make munitions; the locomotives, rolling stock, and track of some entire lines were shipped to the Middle East.

[163] Economic historians such as Prasannan Parthasarathi have criticized these estimates,[51][12] arguing primary sources show Real (grain) wages in 18th-century Bengal and Mysore were comparable to Britain.

[171] Others such as Andre Gunder Frank, Robert A. Denemark, Kenneth Pomeranz and Amiya Kumar Bagchi also criticised estimates that showed low per-capita income and GDP growth rates in Asia (especially China and India) prior to the 19th century, pointing to later research that found significantly higher per-capita income and growth rates in China and India during that period.

[173] The economic problems inherited at independence were exacerbated by the costs associated with the partition, which had resulted in about 2 to 4 million refugees fleeing past each other across the new borders between India and Pakistan.