Economic history of Nicaragua

Nicaragua's economic history has shifted from concentration in gold, beef, and coffee to a mixed economy under the Sandinista government to an International Monetary Fund policy attempt in 1990.

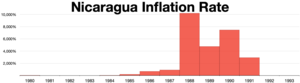

Between decreasing revenues, mushrooming military expenditures, and printing large amounts of paper money, inflation peaked at 14,000% annually in 1987.

The Chamorro administration embraced International Monetary Fund and World Bank policy with the Mayoraga Plan.

Foreign aid and investment had not returned in significant amounts.The first Spanish explorers of Nicaragua found a well-developed agrarian society in the central highlands and Pacific lowlands.

The rich volcanic soils produced a wide array of products, including beans, peppers, corn, cocoa, and cassava (manioc).

[1] By the early 17th century, cattle raising, along with small areas of corn and cocoa cultivation and forestry, had become the primary function of Nicaragua's land.

[2] By the early 1850s, passengers crossing Nicaragua en route to California were served large quantities of Nicaraguan coffee.

[2] Unlike traditional cattle raising or subsistence farming, coffee production required significant capital and large pools of labor.

[2] By the end of the 19th century, the entire economy came to resemble what is often referred to as a "banana republic" economy—one controlled by foreign interests and a small domestic elite oriented toward the production of a single agriculture export.

[3] Under the stimulus of the newly formed Central American Common Market, Nicaragua achieved a certain degree of specialization in processed foods, chemicals, and metal manufacturing.

[3] The 1969 Football War between Honduras and El Salvador, two members of the CACM, effectively suspended attempts at regional integration until 1987, when the Esquipulas II agreement was signed.

[3] Furthermore, the manufacturing firms that had developed under the tariff protection of the CACM were generally high-cost and inefficient; consequently, they were at a disadvantage when exporting outside the region.

[3] The earthquake destroyed most government offices, the financial district of Managua, and about 2,500 small shops engaged in manufacturing and commercial activities.

[3] The government increased expenses to finance rebuilding, which primarily benefited the construction industry, in which the Somoza family had strong financial interests.

[3] The Banamérica Group, an offshoot of the conservative elite of Granada, had powerful interests in sugar, rum, cattle, coffee, and retailing.

[3] The Somoza family owned an estimated 10% to 20% of the country's arable land, was heavily involved in the food processing industry, and controlled import-export licenses.

[4] Armed opposition to the Somoza regimes, which had started as a small rural insurrection in the early 1960s, had grown by 1977 to a full-scale civil war.

[5] After 1985 the government chose to fill the gap between decreasing revenues and mushrooming military expenditures by printing large amounts of paper money.

[5] In early 1988, the administration of Daniel Ortega (Sandinista junta coordinator 1979–85, president 1985–90) established an austerity program to lower inflation.

[5] Years of war, policy missteps due to inexperience, natural disasters, and the effects of the United States trade embargo all hindered economic development.

[6] The president's political coalition, the National Opposition Union (Unión Nacional Oppositora-UNO), was a group of fourteen parties ranging from the far right to the far left.

[6] The Chamorro government's initial economic package embraced a standard International Monetary Fund and World Bank set of policy prescriptions.

[6] The IMF demands included instituting measures aimed at halting spiraling inflation; lowering the fiscal deficit by downsizing the publicsector work force and the military, and reducing spending for social programs; stabilizing the national currency; attracting foreiunign investment; and encouraging exports.

[6] This course was an economic path mostly untraveled by Nicaragua, still heavily dependent on traditional agro-industrial exports, exploitation of natural resources, and continued foreign assistance.

[6] The need to accommodate left and right-wing views within its ruling coalition and attempts to work with the Sandinista opposition effectively prevented the implementation of unpopular economic measures.

[6] Furthermore, foreign aid and investment, on which the Nicaraguan economy had depended heavily for growth in the years preceding the Sandinista administration, never returned in significant amounts.